2022 Global Refugee Work Rights Report

Forward

Throughout the world, refugees and other forced migrants lack the basic rights to work, move, and thrive. A range of legal, administrative, and practical barriers prevent their equitable economic inclusion. Removing these barriers would give displaced people greater agency and power, enabling them to more fully rebuild their lives and contribute to their host communities.

Asylum Access, the Center for Global Development (CGD), and Refugees International are among the organizations at the forefront of this effort. Asylum Access began their Refugee Work Rights campaign in 2010, aiming to catalyze global action to dismantle legal barriers to refugee labor market access. As UNHCR, the World Bank, and other powerful institutions began to address refugees’ access to work, Asylum Access expanded its work on refugees’ rights at work, responding to wage theft, sexual harassment, and other workplace abuses against refugees.

CGD and Refugees International launched their ‘Let Them Work’ initiative three years ago to expand labor market access for refugees and forced migrants in low- and middle-income countries. Let Them Work identifies barriers to refugees’ economic inclusion and provides recommendations to host governments, donors, and the private sector for how to overcome them.

Our shared efforts have had an impact. A new norm is emerging: including refugees in national labor markets is increasingly regarded as good practice. States increasingly acknowledge that honoring refugees’ work rights is good for refugees and good for those who live alongside them. As a result, they are beginning to adjust their laws so refugees can access jobs and benefit from work rights protections.

Much remains to be done, however. This groundbreaking new report documents the extent to which refugees and other forced migrants continue to face barriers in achieving equitable economic inclusion around the world. The data shows that laws protecting refugees’ work rights are often adequate. But in practice, progress is slow and, for many refugees, deeply inadequate.

By highlighting the gap between the rights that refugees and forced migrants have in law and in practice, this report demonstrates the need to focus on implementation. Paper promises are not enough. We must make refugee work rights a reality.

Such efforts are even more important as the world looks to economically recover from COVID-19. While the pandemic has created unprecedented challenges, it has also highlighted the importance of expanding economic inclusion. Refugees and other forced migrants can, and do, play a crucial role within labor markets. Given the opportunity, they can help their host countries recover from this crisis.

We hope this report will be a resource for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers alike, as we all work to realize the moral imperative and practical benefits of refugees’ equitable participation in labor markets. To learn more about our initiatives, please visit our websites and get in touch.

Masood Ahmed, President, Center for Global Development (CGD); Emily E. Arnold-Fernández, Founding President and CEO, Asylum Access; Eric Schwartz, President, Refugees International (RI)

Executive Summary

Refugees’ right to work has been repeatedly recognized in international agreements—from the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees to the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees—and research continues to demonstrate the benefits of this right for refugees and their host countries alike. Yet most refugees today face significant legal and practical barriers to full economic inclusion in the labor markets of their host countries.

While these barriers are widely discussed in general terms, a systematic, public documentation of these barriers is important to advance the efforts toward economic inclusion. For instance, under Objective 2 of the Global Compact on Refugees, to “enhance refugee self-reliance,” two of the four indicators are the proportion of refugees with access to decent work and the proportion of refugees who are able to move freely within the host country. In addition, advocates and researchers have called for a Refugee Policy Index to factor into funding decisions.

Measuring these indicators, however, is a significant challenge. In its 2021 Indicator Report, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) notes that “there is a need to strengthen the measurement of decent work, including by . . . developing the measurement of de facto access to work (e.g., using household surveys).” We view this report and accompanying dataset as contributing to this effort.

In this project, produced by researchers at the Center for Global Development (CGD), Asylum Access, and Refugees International, we assess refugees’ work rights across the globe. We examine different dimensions of work rights both in law (de jure) and in practice (de facto) across 51 countries that were collectively hosting 87 percent of the world’s refugee population at the end of 2021. Combining legal documents, country-level reports, news articles, and input from more than 200 practitioners with knowledge of refugees’ livelihoods and use of services, we evaluate the de jure and de facto situation within a standardized framework. We believe that the findings and accompanying dataset will be critical tools for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers on refugees’ work rights.

Key Takeaways

- Every country in this study imposes barriers to refugees’ work rights in practice.

- There is a stark difference between refugees’ overall work rights in law and in practice.

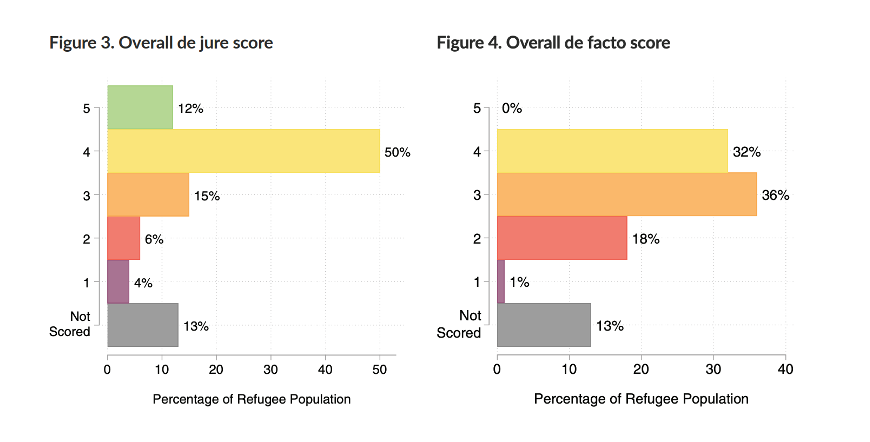

- At least 62 percent of refugees live in countries where the legal framework for work rights is adequate or better (a 4 or 5 on our five-point scale).

- Yet many of these laws are not widely implemented: at least 55 percent of refugees live in a country that significantly restricts their work rights in practice (a 3 or below on our scale), and at least 19 percent of refugees live in a country that severely restricts their right to work in practice (scoring a 1 or 2).

- High-income countries often offer strong work rights—both de jure and de facto—to recognized refugees. However, they also prevent access to these work rights in practice by significantly limiting refugee status (i.e., asylum), restricting the work rights of asylum seekers, and limiting the territorial access of would-be asylum seekers in some cases. Other countries that offer strong de jure work rights frequently fail to issue the necessary work or business permits to refugees specifically or impose other administrative or enforcement barriers.

- While the law is not enough to guarantee refugees’ right to work, it is oftentimes a necessary starting point: de jure and de facto scores are strongly correlated, and only 3 of the 19 countries in our sample that have adequate access in practice do not have adequate access in law.

- Amid hope for the Global Compact on Refugees and fear over the impact of COVID-19, we do not see a significant net change in the right to work over the last five years. Approximately 28 percent of the global refugee population lives in a country where access to wage employment in practice has improved, while 29 percent lives in a country where it has worsened.

- We also study additional factors that are critical to refugees’ work rights and economic inclusion in practice, such as access to services and documentation.

- Education is the most accessible factor in our data: at least 64 percent of refugees live in countries that provide adequate access to basic schooling in practice, with similar access— for at least 60 percent of the refugee population—to secondary school.

- In contrast, formal financial services and credential certification are the least accessible factors: only 2 percent of the refugee population has adequate access to formal financial services, and only 10 percent can generally certify academic and professional credentials from their country of origin.

Main Findings

In this section, we summarize our data on refugee work rights in law (de jure) and in practice (de facto). We evaluate the situation as of 2021, explore how de jure and de facto conditions correlate, and examine the relationship with other factors such as the number of refugees a country hosts. The following conclusions are solely drawn from the sample in our data (see Figure 2).

De Jure Score Summary

For refugees’ de jure work rights, 9 out of 51 countries in the sample received a score of 5 (green), meeting the criteria that “fully-functioning national policies support refugees’ right to work without restrictions and extend labor protections to refugees.” These 9 countries host 12 percent of the global refugee population (Figure 3 below). Another 50 percent of refugees live in the 21 countries that scored a 4 (yellow), which means more than half of the world’s displaced population lives in countries that generally respect refugees’ work rights by law. We consider a country to be significantly restricting refugees’ work rights in law and policy if it scores a 3 (orange), 2 (red), or 1 (purple) on de jure rights.

Notably, income levels do not correlate with de jure scores. In fact, low-income countries in this sample had the strongest performance on refugee work rights in law, with 3 out of the 8 low-income countries receiving the top score (5/green) and 3 more receiving a 4 (yellow). None of the low-income countries received either of the lowest two scores.

Middle-income countries had the lowest de jure scores, on average, in the sample. Seven of the the 8 countries that received the two lowest de jure scores (1/purple or 2/red) are middle-income. Three of 6 lower-middle-income countries scored a 4 and none scored a 5, while 10 of 20 upper-middle-income countries scored a 4 or 5.

Only 3 of 17 high-income countries received the top score. Eight received the second-highest score and 5 received a 3. For most of the high-income countries on this list, their score of 4 (yellow) reflects a waiting period of two to nine months before asylum seekers can lawfully access work, sometimes accompanied by other bureaucratic obstacles. The remaining high-income country, Hong Kong, received the lowest score.

De Facto Score Summary

On average, de facto scores are lower than de jure scores. No country in the sample received the top score for labor market access in practice. Instead, at least 55 percent of the global refugee population lives in a country that significantly restricts refugees’ work rights in practice, scoring a 3 (orange) or below (Figure 4). This includes 19 percent living in countries that severely restrict work rights—18 percent in countries scoring a 2 (red) and 1 percent in Tanzania, the only country to receive the lowest score. These figures likely underestimate the extent of restrictions globally, as 13 percent of the refugee population was not covered by our survey.

In contrast to de jure scores, de facto scores are correlated with income level. High-income countries have the highest average scores, with 11 out of the 17 scoring 4 out of 5. Five countries received a score of 3, while Hong Kong scored a 2. The 6 lower-middle-income countries scored the lowest, on average, with none receiving a score of 4 or 5. Upper-middle-income and low-income countries scored similarly, averaging about 3. While there is a correlation between income and de facto score, low-income countries Rwanda and Uganda scored as high as any high-income country.

Our de jure findings are based on analyses of national, regional, and international law that mandate the work conditions in host countries for people who have been forcibly displaced. Our de facto findings are based on a survey of practitioners in the 51 refugee-hosting countries, as well as supplemental desk research. Countries were scored on questions regarding wage employment, self-employment, mobility, and access to services, in most cases relative to host-country citizens’ access. We use a government’s treatment of its citizens as the benchmark in order to isolate the discrimination faced by refugees in particular.

Our focus is on the actions (or inactions) of host governments. Our aim is to catalog issues such as an inability to access work or business permits, the potential for fines or arrest while traveling or living outside a camp, or differential enforcement of labor protections for refugees relative to host-country citizens. These are practices that are under the direct control of governments and specific to refugees. They contribute to, but are distinct from, self-reliance outcomes such as employment or wages, where poor outcomes, or even differences between host communities and refugees, do not necessarily signal government barriers.

Both access to and rights within the labor market are important to refugees, enabling them to support themselves and their families, build their skills, promote mental health, and contribute to their host country during periods of displacement. Refugees’ labor market access also benefits host communities on net, opening new employment avenues for host workers, generating additional consumer spending, and expanding the tax base, oftentimes without displacing host workers. The full benefits can only be achieved, however, if refugees can work without sector or geographic limits, move freely, and enjoy robust protections both in law and in practice.

Recommendations to Expand Labor Market Access

Refugees’ right to work is repeatedly articulated in international legal instruments. In addition, most studies find that when refugees and asylum seekers are given the right to work, move, and thrive, they contribute to the socioeconomic development of their host countries. Our study documents numerous legal and practical barriers that deny refugees their rights and prevent refugees and host countries from fully realizing the economic gains.

The recommendations below are principles and ideas to address these barriers. They are targeted at refugee-hosting countries and donors, and outline ways in which they could improve both their policies and implementation to safeguard refugee rights. They are not conclusions derived from our main data; instead, they are proposals to address the issues highlighted by our analysis based on the experience of our organizations and many others.

Host countries should:

- Ensure that domestic laws grant refugees the right to work and freedom of movement, and that these rights are upheld in practice. Refugees should be included as constituents in work rights policymaking and accountability mechanisms.

- Automatically include the right to work and freedom of movement as integral aspects of refugee status and state these rights clearly on documentation issued to refugees. Requiring separate work permits creates an unnecessary barrier that adds bureaucratic delays and sows confusion among employers and refugees alike.

- Safeguard refugees’ rights at work through enforcement and support legal aid for refugees who experience workplace violations.

Donors should:

- Incentivize host governments to expand refugees’ right to work. Some concessional funding should be tied to policies and implementation of refugees’ rights. Initiatives like the World Bank’s IDA19 Window for Refugees and Host Communities, which is accompanied by a framework to document each host country’s progress on refugees’ rights, should be strengthened and expanded.

- Strengthen accountability mechanisms for Global Refugee Forum (GRF) pledges and involve experts (including refugees) in designing and implementing these accountability mechanisms.

- Support local organizations advocating for refugees’ work rights.

- Provide support to host communities in addition to refugees. While most research finds refugees have a small average effects on hosts’ economic outcomes, some groups can be negatively affected. External support can mitigate negative effects and reduce opposition to labor market access for refugees.

The recommendations target both laws and practices. Our study shows that refugees’ access to labor markets in practice is correlated with policies that enable this access. While policies permitting labor market access are not enough, a lack of such policies—or policies directly prohibiting this access—can pose an insurmountable barrier to equitable labor market access for refugee populations. Every host country is different, and therefore specific recommendations should be tailored for each country. Yet, in general, enacting the right policies is a necessary first step toward ensuring refugees’ equitable access to fair, safe, and lawful work.

Our study also shows that policy improvements alone are not sufficient to create pathways to refugees’ equitable labor market access. Unless these policies are implemented and enforced, they will remain promises on paper, divorced from the daily lives of refugees.

Cover photo: Coding school helps women refugees hone tech skills in Germany, March 24, 2018. Photo Credit: UNHCR.