Malaysia: Rohingya Refugees Hope for Little and Receive Less

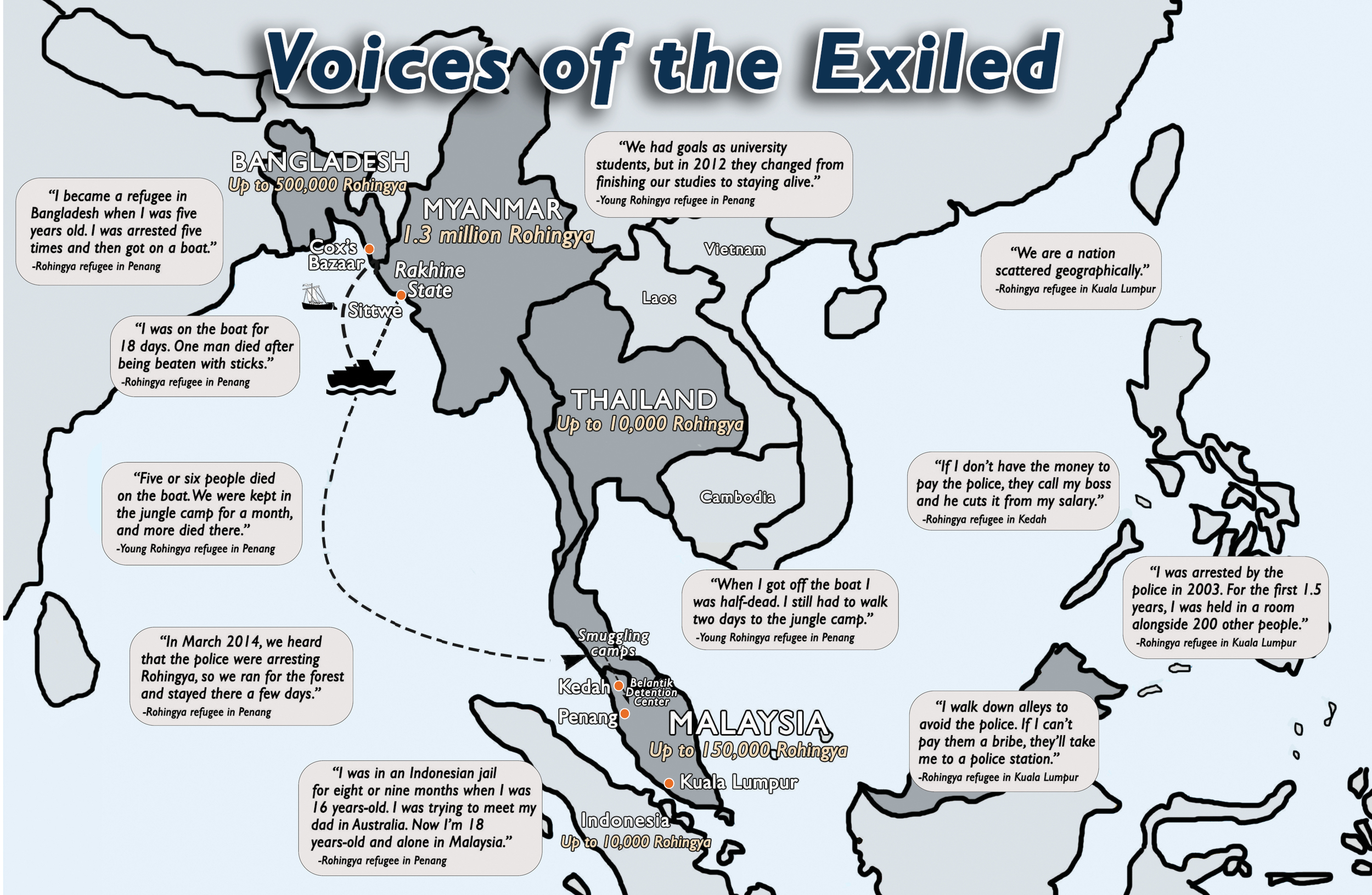

It’s been six months since as many as 1,000 Rohingya fleeing from Myanmar died in the Andaman Sea. And still, neighboring nations remain resistant to recognizing the Rohingya people’s rights as refugees.

Even after neighboring governments met earlier this year and agreed to protect the Rohingya at sea, no nation has taken a leadership role in permitting them to disembark from boats safely and legally. The absence of a regional plan leaves the Rohingya vulnerable to the challenges of a perilous sea voyage, and further strands those Rohingya who have lived in Malaysia and other regional nations for up to three generations without legal rights or protection. Without a doubt, Myanmar is creating this crisis. But that fact does nothing to negate the rights of Rohingya to remain in neighboring nations while serious threats to their lives exist in Myanmar, and to be treated with dignity and respect. Regional nations, particularly Malaysia, must act now to ensure that Rohingya fleeing persecution can disembark from boats and secure protection, and that those already inside Malaysia can live in safety and without the constant threat of detention and extortion by the police. It is past time for the international community to demand more from both Myanmar and neighboring countries, as well as the UN agencies mandated to protect the Rohingya.

Background

With at least 1.5 million people in the diaspora, there are already more Rohingya exiled outside Myanmar than living inside. The Rohingya have been fleeing persecution in Myanmar’s Rakhine State for decades. The first large exodus occurred in the 1970’s, when 250,000 Rohingya were forced out of their homes and into Bangladesh by the Myanmar military. While some returned in the interim, another mass purge occurred in 1991 and 1992. Most of this population was then forcibly returned to Rakhine State with the assistance of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in the mid-1990s. In the early 2000s, attacks on Muslim places of worship and schools caused new flight, primarily to Bangladesh. During each of these exoduses, some Rohingya went to other regional nations, including Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. Most recently, state-orchestrated violence in Myanmar in 2012 forced the displacement of 140,000 people and the death of more than 200 Rohingya. Since then, more than 100,000 Rohingya have fled Rakhine State by boat, and more than 1,000 have died during the journey.

“The Rohingya community is looked at as a “thing”,

Community Based Organization worker in Kedah

a situation, not people.”

Recommendations

Malaysia should take on the primary role of refugee protection inside the country with the assistance of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), by:

Formulating law and policy that provides individuals and families seeking protection from refoulement with a fair, full, and transparent opportunity before an independent and qualified body;

Identifying and regularizing the status of refugees in need of protection, and holding the police and employers accountable for exploiting them, including through bribes, sexual and physical violence, or other criminal acts;

Issuing work permits to all refugees and protecting their workplace rights as set forth in the 16 International Labor Organization conventions already ratified by Malaysia;

Ensuring that alternatives to detention are made available to refugees, and alternatives to detention – such as conditional release – be considered before resorting to detention;

Extending access to public education for refugee children; and

Providing refugees with access to affordable health care.

In line with Malaysia’s Federal Constitution, the nation should recognize Rohingya children as citizens by operation of law if they were born in the Malaysian Federation and cannot acquire citizenship of another country by registration within one year of birth;

Consistent with the May 29 Regional Conference’s resulting agreement, governments in the region, including Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand, should compose a Task Force focused on:

Generating political will and strengthening regional cooperation to protect and facilitate the ability of individuals and families to flee situations of persecution, while also combatting human trafficking and smuggling;

Addressing the root cause of Rohingya flight by directly challenging the Myanmar government to recognize Rohingya people as citizens; restore their right to vote, freedom of movement, and access to education, health care, and livelihood; and promote their ability to return from displacement camps to their places of origin;

Developing affordable, accessible, and safe avenues for migration and improving labor-monitoring standards for all refugees and migrants.

ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) member states should:

Agree on what constitutes a situation of distress at sea, agree on safe ports for disembarkation, and determine how nations with safe ports will be financially and technically supported regionally; and

Ensure that all border governance measures taken at international borders, including those aimed at addressing irregular migration and combating transnational organized crime, are in accordance with the principle of non-refoulement and the prohibition on arbitrary and collective expulsions.

Until the Malaysian government assumes responsibility for refugees, UNHCR should:

Broaden its outreach with Rohingya communities, strengthen existing partnerships, and greatly increase the registration of Rohingya refugees across Malaysia;

Make greater efforts to identify and support Rohingya people with life-threatening injuries and ailments, and support programs to care for chronic and trauma-related illnesses; and

Explore opportunities to increase financial and technical support to “learning centers” so that they can serve all school-aged refugee children and ensure that trained teachers are in classrooms.

Sarnata Reynolds and Ann Hollingsworth traveled to Malaysia and Thailand in September and October 2015 to assess the situation for Rohingya refugees.