Efforts to Localize Aid in Ukraine One Year On: Stuck in Neutral, Losing Time

Executive Summary

February 24, 2023, marks the first anniversary of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. The war unleashed the largest humanitarian and refugee crises in Europe since the Second World War. Ukrainian civil society, volunteer networks, and local officials rose to the challenge and mounted one of the most effective homegrown humanitarian relief efforts in history. In the months that followed, international aid organizations scaled up a massive humanitarian operation alongside the Ukrainian effort.

As the international response took shape, it began to crowd out what Ukrainian civil society and local officials had achieved. By the summer of 2022, Ukrainian and international organizations, including Refugees International, specifically warned that the failure to give Ukrainians greater control over international aid flowing into their country undercuts the effectiveness of the relief effort. It also squanders an important opportunity to implement reforms and power shifts long called for across the aid sector.

It is important to note that some progress has been made. A range of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), UN agencies, and country donors have signaled greater commitment to localization in Ukraine. They have pledged to take specific steps to shift decision-making power and financial resources to Ukrainian actors in line with multiple such commitments made over the years.1

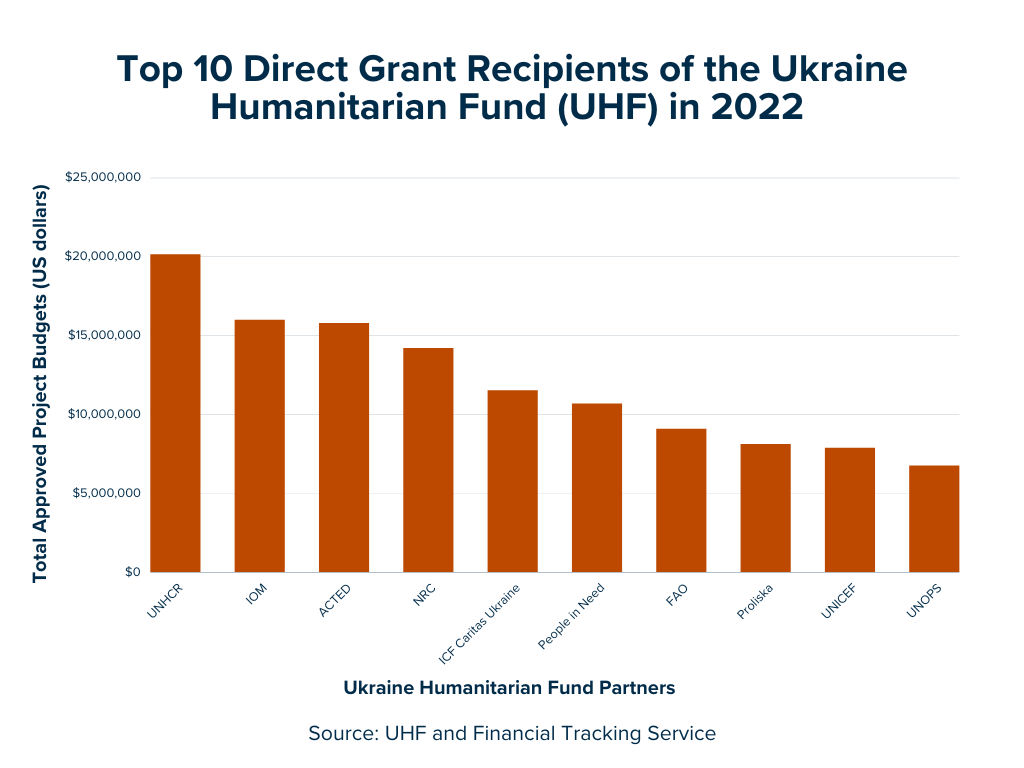

In addition, the UN’s Ukraine Humanitarian Fund (UHF), the largest UN country-based pool fund (CBPF) in the world, has doubled the percentage of funding allocated to local/national non-governmental organizations (L/NNGOs) from 18 precent in the summer of 2022 to 33 percent overall in 2022. Several donors have launched small pilot projects this past fall to deliver funds directly to Ukrainian organizations, and some INGOs have formalized “equitable partnership”2 arrangements.

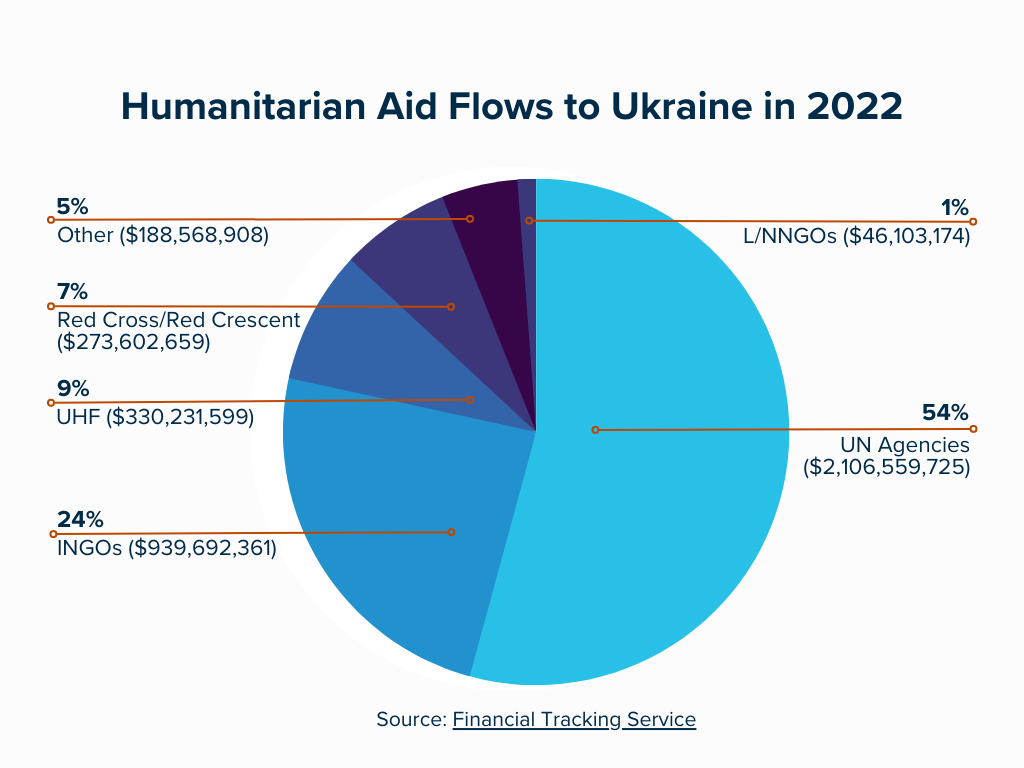

However, action by the international community has not kept pace with its rhetorical commitments. Most efforts to localize aid in Ukraine are yet to gain traction. As a result, the international aid economy that took root last spring continues to expand. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the number of aid organizations working in Ukraine has increased five-fold since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022.3 More than 60 percent of these organizations are Ukrainian. Yet less than 1 percent of the $3.9 billion tracked by the UN in 2022 went directly to local actors. Instead, the United Nations and international NGOs received nearly all donor funds sent or on the way.

In addition, effective coordination across international and Ukrainian organizations remains elusive. A limited number of Ukrainians do participate in international mechanisms like the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT), the UN’s main coordination body. But few Ukrainians have what they would regard as a meaningful role in decisions over how and where international aid money is spent. Instead, most local responders tend to coordinate through extensive networks of their peers at the oblast or municipal level. As a result, foreign aid workers and their Ukrainian counterparts operate in parallel systems – at times unaware of each other.

Recent trends suggest that the internationalized aid effort in Ukraine faces significant challenges. To date, the response has been exceptionally well-funded, but that will be increasingly hard to sustain as the conflict drags out. Resources will become scarcer just as humanitarian indicators worsen by the month, in part due to sustained Russian strikes on vital infrastructure.4 In addition, a new round of offensives looks set to kick off in the spring. As new fighting intensifies, it will be the Ukrainians who have the greatest ability to deliver the “last mile” of the relief effort to frontline communities.

The good news is that Ukrainian NGO leaders are clear on what needs to change. Over the last four months, Refugees International has co-organized localization consultations around the country with Ukrainian and international relief groups. During these sessions, Ukrainians asked for more direct and multi-year funding and capacity building for Ukrainian responders. They also pleaded for harmonized vetting processes, so they do not waste time answering the same questions from different donors. Local groups want to partner as equals with their international counterparts and urged the latter to stop poaching their best staff. Finally, they called for coordination mechanisms to be tailored to the Ukrainian reality rather than insisting Ukrainians adapt to international models.

The bottom line is that Ukraine will need to do more with less under worse conditions. It is therefore incumbent on donors to make sure these funds are spent with maximum efficiency and maximum empowerment of Ukrainians. It is not too late to act—but several steps will have to be taken as soon as possible.

Recommendations

- Donor countries should base staff in Ukraine and engage a wide spectrum of Ukrainian civil society groups in regular and direct dialogue. Donors with embassies in Ukraine should deploy aid staff on a permanent basis and travel around the country to build partnerships with Ukrainian humanitarian responders. These responders should include volunteer networks, women-led organizations, and organizations serving marginalized populations.

- Donor countries should mandate that international aid organizations commit to equitable partnership and ethical hiring guidelines. These reforms would ensure, among other things, that local organizations (including sub-grantees) receive fair compensation for their overhead costs and that international agencies do not distort the local labor market. Donors should monitor compliance with these commitments and collect data on the amount of funding passed through international aid groups to local sub-grantees. Donors should also better publicize funding opportunities and opportunities for involvement in coordination structures, especially in local languages.

- UN agencies and international NGOs should publicly commit to concrete deadlines and benchmarks to advance localization. International aid organizations need to go beyond aspirational objectives by developing publicly available localization strategies. These strategies should set out specific timelines with targets to steadily move the ownership of funding and programs as much as possible to Ukrainian NGOs and volunteer networks.

- The United States and European donors should increase support for the Ukraine Humanitarian Fund (UHF) this year. The UHF is the main vehicle for directly funding Ukrainian relief groups. As such, it offers one of the most immediate ways to advance the localization of aid funding. DG ECHO does not provide any funding to the UHF, while USAID provides only a relatively small amount ($20 million). However, increases in funding should be conditioned on localization reforms (see below).

- The UHF should set ambitious targets and ensure that its international grantees abide by good localization practices. These include instituting equitable partnership and ethical hiring requirements with its grantees. In addition, the fund should commit to increasing the percentage of funding directed to Ukrainian relief groups and volunteer networks up from the current 33 percent to at least 65 percent on an annual basis.

- The UHF should significantly scale up its existing $20 million envelope to support smaller volunteer networks, civil society organizations, and L/NNGOs. It should also press the Humanitarian Response Plan to allow for funding beyond 6 to 12 months. The fund should prioritize L/NNGO funding applications over INGO and UN applications in particular to help raise the percentage of funding to local actors.

- The UHF should issue specific funding calls or new “envelopes” that would address barriers to localization. There are at least four specific areas that should be targeted as they have proven especially problematic when it comes to localizing aid: organizational strengthening; anti-corruption mechanisms; enabling the separation of civilian and military aid activities; and enhancing Ukrainian coordination and engagement platforms. The fund should also consider issuing micro-grants for those L/NNGOs that need assistance in applying for UHF funding calls while committing resources to a robust outreach and communications strategy in local languages.

- If the UHF fails to expand funding to Ukrainian groups and undertake other localization reforms, donor states should partner with INGOs to establish a new pooled fund specifically for Ukrainian relief groups. Such a pooled fund could rely on INGOs as the financial pass-through and administrative foundation of the fund. However, decision-making and overall leadership of the fund should rest with Ukrainian L/NNGOs, which would set priorities and budget allocations. Its main objective would be to directly fund Ukrainian humanitarian responders, but it could also channel funds to the four specific areas identified above that have proven especially problematic when it comes to localizing aid.

- International coordination mechanisms like the Humanitarian Country Team and the cluster system should set near-term timelines for increasing Ukrainian participation and leadership. The United Nations, specifically, should insist that Ukrainian organizations fill the majority of NGO seats at the HCT coordination table. The new NGO Platform bringing together INGOs and L/NNGOs should ensure that a comprehensive set of localization principles are agreed upon by all member organizations as a prerequisite for joining.

- Donors, INGOs, and UN agencies should proactively engage and support existing Ukrainian coordination mechanisms. International actors should reach out to and invest in the multitude of Ukrainian-led humanitarian coordination mechanisms that have progressively been built out over the last year. They should incentivize Ukrainians to participate in internationally led coordination mechanisms and invest in building bridges between local and international platforms.

Methodology

This report is based on Refugees International research in Ukraine in February 2023 and November and December of 2022, as well as remote interviews with a range of relevant actors and the work of both the informal Advocacy Working Group Sub Group on Localization and the Disaster Emergency Committee’s Scoping Survey. It serves as an update to Refugees International’s previous report on this issue, based on visits in June and July 2022 to humanitarian operations in several key oblasts across Ukraine, specifically Kyiv, Lviv, Zaporizhzhia, Dnipro, and Odesa.

Refugees International’s findings and recommendations build on the work of several individuals and organizations, most notably, Humanitarian Outcomes, ACAPS, Caritas Ukraine, the National Network of Local Philanthropy Development, the UK Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) “Scoping Report,” and others that have been warning about a major shortcoming when it comes to the significant international aid now flowing to Ukraine and the failure to swiftly and extensively localize the humanitarian response.

These findings and recommendations are applicable to those areas controlled by the Ukrainian government. Humanitarian responses in Russian-occupied areas or those areas seized by their proxies since 2014 present a series of additional complications and considerations that require separate investigations.

Humanitarian Data Points

- According to data from OCHA, by February 10, 2023, 17.7 million Ukrainians were in need of humanitarian assistance, 5.4 million were internally displaced, and 8 million were considered refugees in European countries.

- By the end of 2022, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recorded 17,994 civilian casualties in the country, including 429 children killed and 808 injured. The number represents only a fraction of the actual toll, as the verification process has faced immense challenges.

- By early January 2023, Ukraine’s Ministry of Education reported that over 2,600 education facilities had been damaged and over 400 schools had been completely destroyed across Ukraine. In the last three months of 2022, it is estimated that at least half of all online classes were also canceled as a result of missile strikes and loss of power, internet, and heating.

- According to the January 2023 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO), approximately 14.7 million people, including more than 5.5 million internally displaced people, more than 5 million non-displaced individuals, and more than 3.6 million returnees need specialized protection services. Among them, 56 percent are female and 44 percent are male.

- One-third of all households in Ukraine were food insecure and 5 percent were extremely food insecure in 2022. A further 28 percent were moderately food insecure or experienced food consumption gaps and an inability to meet food demands without using negative coping strategies.

- More than 10 million people in Ukraine received food assistance in 2022, and the demand is growing. Humanitarian needs in areas where ongoing hostilities continue to escalate are increasing.

- In order to meet the growing needs for heating and power amid the energy crisis, OCHA reports that by the end of 2022, some 770 generators have been delivered by humanitarian partners across hospitals, schools, heating points and collective centers, while at least 2,300 more have been procured or are on their way to Ukraine.

Growing Rhetorical Commitment to Localization

In December 2022, some of the largest donors to the Ukrainian response issued a “Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development” at the Effective Development Cooperation Summit in Geneva. Donors committed to “shift and share power to ensure local actors have ownership over and can meaningfully and equitably engage” in relief and recovery efforts. Signatories pledged to “reinforce local leadership and ownership, and reposition ourselves and other international actors as supporters, allies, and catalysts of a more inclusive, locally-led, co-created, and sustainable approach.”

A few months before, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) released an extensive draft report calling for a major effort to localize aid across the agency. The report and subsequent statements committed USAID to use its money and influence to drive change across the global aid ecosystem.5 During the same period, Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) undertook an extensive study of its own global programs and commitments to localization. As a result, the European aid agency mandated that several key localization principles must be applied by their grantees. In late October 2022, some of the largest international NGOs operating in Ukraine signed onto the “Pledge For Change.” The pledge commits signatories to “allocate more resources to help local and national organizations take the lead” across their global operations.

In Ukraine, UN agencies conducted an extensive localization review in the late fall of 2022 with Ukrainian partners and international NGOs. The upshot was a commitment to make concrete improvements in localization across the board and specifically in cluster coordination. As part of the process, the UHF—now the largest UN country-based pool fund (CBPF) in the world at $327 million6—doubled the funding allocated to Ukrainian groups from just 18 percent in the summer of 2022 to 33 percent.

Over the last several months, there has been a notable increase in Ukrainian engagement around localization. In December 2022, a UK Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) “Scoping Report” found that two-thirds of Ukrainians expressed high confidence in understanding and explaining both humanitarian principles and localization. Five consultations across Ukraine that Refugees International conducted in partnership with several other INGO and L/NNGOs between November and December 2022 similarly revealed a robust awareness and debate amongst Ukrainian L/NNGOs about partnerships, funding, and relationships with international actors.

During these consultations, Ukrainians identified five specific areas that need immediate action. These included 1) expanded funding for L/NNGOs; 2) the harmonizing of verification processes; 3) support for capacity expansion; 4) the enforcement of equitable partnerships and ethical hiring practices;7 and 5) the tailoring of coordination mechanisms to Ukrainians rather than having Ukrainians wholly adapt to international models. Ukrainians also called for a new, more flexible pool fund for L/NNGOs. This fund would allow for due diligence approvals done by one aid agency to be used by or “passported” to from other aid agencies. It would also support coordination mechanisms for L/NNGOs and facilitate engagement and leadership in the formal Cluster coordination system.

Localization Efforts Remain Largely Stalled

Donors Have Yet to Walk the Talk

Positive statements and clear recommendations have not, however, translated into much change on the ground. Four billion dollars in humanitarian aid to Ukraine has been committed or delivered since the end of summer 2022. This is on top of the $12 billion committed or delivered since February 2022. However, almost all donors have avoided directly funding Ukrainian civil society. The largest single humanitarian aid donor, USAID, has not engaged in direct humanitarian grant relationships, including with some of the largest national NGOs who have been recipients of U.S. funds in previous years. Because of legal restrictions prohibiting funding for non-EU located agencies, DG ECHO also has yet to provide a single euro directly to a Ukrainian organization, despite the country’s candidacy for the European Union.

There have been some exceptions to this trend lately. Several pilot localization projects have been launched, such as the Kyiv UK Embassy’s direct funding call for L/NNGOs and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation’s expressed interest to fund localization initiatives. But even these small-scale efforts reveal the disconnect between large donors and local organizations. For several weeks after it was first posted, for example, the UK Embassy’s call for proposals was only available in English.

ECHO now requires equitable partnerships for sub-grantees in Ukraine. However, it remains unclear what the consequences for noncompliance are or even what ECHO considers equitable (what percentage is “fair” for sub-grantee overhead?). Moreover, ECHO and USAID do not track and make publicly available how much of their funding is flowing from both INGOs and UN agencies to Ukrainian sub-grantees.9

The United Nations Humanitarian Country Team

In November 2022, the UN’s main coordination body, the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT), pledged to prepare a localization action plan on short-term impact priorities and to establish a consultative body. However, these initiatives have yet to materialize. The HCT also said it would support doubling Ukrainian representation from the current two to at least four L/NNGOs out of its 19 members. However, this initiative has been delayed until a mixed international-national “NGO Platform” is established sometime in late February or March 2023. This NGO Platform would then elect L/NNGOs and INGOs to the new, expanded HCT table.

Additionally, there are still no publicly accessible means to track localization-specific objectives. The UN’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) does not adequately account for transfers made by partners or UN Agencies to local organizations. The HCT has yet to develop a clear and measurable “transfer and exit” strategy for UN agencies. Nor has the country team mandated equitable partnership or ethical hiring practices, although both have been tabled. Although it may do so soon, it remains unclear what the tracking and reporting mechanisms will be or if there will be any consequences for breaches by agencies.

Furthermore, L/NNGOs have repeatedly but unsuccessfully requested that international organizations use a single common vetting standard for their partner evaluations. Indeed, one major INGO reported to Refugees International that UN agencies simply do not have the internal buy-in to practically engage in any transfer of vetting credentials or information across agencies. Staff from other INGOs echoed this complaint in interviews when it came to their own compliance departments, which largely refuse to accept the vetting of other INGOs or UN agencies.

L/NNGO involvement as prime grantees in the $1.1 billion Multi-Purpose Cash program directed by the UN—its single largest program—was also extremely limited. Over the past year, only 90,360 people (1.7 percent) out of the 5.26 million Ukrainians who received cash via UN funds did so directly from a L/NNGO prime grantee.

The Ukraine Humanitarian Fund

The UHF, as noted above, has been more successful. In September 2022, the UN fund launched a $20 million “envelope” or funding call specifically earmarked for “enabling actors to partner with national and local partners.” According to a preliminary accounting, 13 Ukrainian and international organizations received funding, with more than 300 smaller Ukrainian organizations receiving funding as sub-grantees. Most encouraging, as much as 70 percent of the total funding is believed to have been budgeted for transfer to the 300 organizations. However, the UHF is uncertain whether it will continue the program.

Moreover, all allocations from the UHF are made on six or 12-month bases, pegged to the annual Humanitarian Response Plan. As a result, the Fund cannot meet the oft-heard requests of L/NNGOs (and INGOs for that matter) for stable, multi-year funding. The UHF has yet to institute clear and firm requirements for equitable partnership and ethical hiring practices, instead electing to simply “prioritize” them. In a positive step, the UHF is rolling out a new tracking system that will allow the Fund to monitor overhead percentages across grantees and sub-partners. But, in the end, the UN’s Pool Fund in Ukraine still falls short of the mark it reached in 2021 when almost 50 percent of grants flowed directly to L/NNGOs.

A recent DEC scoping survey found that most Ukrainian organizations have little knowledge or awareness of the Fund. Those that do found it difficult to comply with the list of UHF conditions to obtain an award. As the survey report remarked, “The UHF plans to increase awareness and outreach among smaller L/NAs. However, a recent online information meeting for prospective applicants was conducted only in English, with reported requests for it to be in Ukrainian denied.”

International NGOs Continue to Expand

In recent months, the large international NGOs have continued to deepen their presence in Ukraine, increasing from around 20 in the spring of 2022 to almost 70 in December 2022. There are likely hundreds of small and medium-sized INGOs engaged across Ukraine as well.10 According to ICVA, local actors are, “losing operating space as well as significant numbers of their skilled workforce, often directly to their international partners as the drive for scale exceeds other considerations.” Some INGOs have established innovative partnership models, and several are engaged in consolidating “transfer and exit” strategies. But these examples are in the minority.

INGOs have scrambled for almost a year now to build out durable partnerships, engaging dozens or even hundreds of L/NNGOs and volunteer networks in the process. However, many of the larger INGOs and UN agencies are currently only formally working with a small number of local partners. It is therefore also not surprising that ICVA’s December Mission Report concluded that, “there is a widespread view the response is collectively failing to live up to the localization commitments made through the Grand Bargain or otherwise.”

Coordination: A Tale of Two Responses

Ukrainian participation in international coordination mechanisms remains wanting.11 As one top European Union aid official observed, “It’s very clear that we are still living in two parallel universes when it comes to coordination and responding: An internationally dominated one and a Ukrainian one.” A limited number of Ukrainians have managed to participate in international coordination meetings. But Refugees International’s regional convenings and the DEC Survey found that few Ukrainians believe these opportunities lead to meaningful and useful engagement. “When we promote participation,” explained Fredric Larsson from the Ukrainian NGO Resource Center, “the feedback received is often that the Cluster meetings are heavy-handed, presentations come from the big organizations… And there is of course the lack of dialogue and interaction in the meetings, the lack of explanations, all of which leads Ukrainians to not see the practical benefits.”12

There are, however, more explanations for the lack of Ukrainian involvement in international coordination structures. First, according to some L/NNGOs, at least until October 2022, many Ukrainian responders were keeping their operations running with volunteers, charitable donations, and in-kind aid pouring into the country from abroad. This meant that L/NNGOs were not forced to divert their limited time and staff resources to engage with opaque foreign coordination structures. For the first nine months of the current crisis, Ukrainian responders appeared to have found it simpler to operate in their own “universe” divorced from the international response. In parallel, international actors built out their own “universe,” albeit with the latter steadily drawing in more and more L/NNGOs as sub-grantees and acquiring more talented Ukrainians as contractors or full employees.

A second reason for these “two universes” lies in the increasingly strong Ukrainian coordination mechanisms that L/NNGOs have built out across civil society and some governmental authorities. As ICVA observed in December, coordination across Ukrainian civil society groups and local authorities, “is widespread and appears both sophisticated and effective in delivering assistance to large numbers of people.” These Ukrainian coordination mechanisms are often decentralized and rooted in local social media networks exclusively in the Ukrainian language. International actors struggle to access these Ukrainian coordination platforms, and many are unaware they exist.

Finally, Ukraine presents an unfamiliar landscape for many recently arrived humanitarians. Unlike many other war zones, Ukraine has a relatively strong state. Regional administrations and city councils have established “humanitarian hubs.” There are relatively well-developed state-society communication mechanisms. As Dina Urich from the volunteer-driven Ukrainian NGO Helping to Leave observes:

“The coordination mechanisms do exist.13 We cooperate with many partners on the ground and with the authorities,14 and it is proven to be successful. Mechanisms such as maintaining a common database, separating the logistical part from actual work on the ground, quick and constant communication, among a multitude of partners and volunteers… We were able to get 23,000 people out of the deoccupied Kharkiv region by activating our coordination network with the Ministry, the Kharkiv authorities, and the Kharkiv Red Cross who all agreed to send all of their evacuation requests to our Helping to Leave database so that we could process it at one single point and then coordinate the local volunteer deployment and funding needs.”

Ukrainian Coordination Mechanisms

Caritas Ukraine’s Olesia Balyan highlights a small sampling of Ukrainian coordination mechanisms that are a part of the wider ecosystem trying to efficiently and effectively house, feed, move and assist Ukrainians:

- SpivDiia is coordinated with the support of the Humanitarian Headquarters for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid of the Office of the President of Ukraine. People can request or volunteer help by registering on the website or through Telegram. https://spivdiia.org.ua/en

- Palyanitsa.Info is an open database of organizations that provide humanitarian and volunteer assistance to the population throughout Ukraine. The platform was created by the Ukrainian Volunteer Service together with the IT company SoftServe to help people during a full-scale war. Palyanitsa.Info has more than 950 organizations and initiatives that are regularly updated. The portal was created to simplify the search for help and make it more efficient. The organizations are divided into 15 categories and are distributed according to locations in Ukraine. Each organization added to the platform is verified by the Ukrainian Volunteer Service. https://palyanytsya.info/

- Ukrainian Volunteer Service is a non-profit organization whose mission is the formation of a culture of volunteering and mutual assistance in Ukraine. It has a web page where people can register as a volunteer and offer help and expertise. People can also use this platform to find volunteers if they need help. https://volunteer.country/

- Lviv’s city support center for internally displaced people works as a coordination center from the Lviv City Council and offers information about arriving in Lviv, including how to find a house, where to draw up necessary documents, how to get social and humanitarian aid, etc. https://city-adm.lviv.ua/help

- Prykhystok is a government initiative that helps to provide housing options for internally displaced people throughout Ukraine. People with a free room/apartment/house can register that they have a living space available. Internally displaced people can browse the site to find housing options. https://prykhystok.gov.ua/

Barriers To Localization

The main structural barriers that prevent the localization of aid in Ukraine are well known (as they are elsewhere in the world). The first barrier regularly cited by international actors in Ukraine is that most Ukrainian relief groups cannot meet donor and aid agency reporting requirements. International officials acknowledge that Ukrainian civil society has demonstrated a high capacity in responding to the needs of their fellow citizens. But these groups struggle to navigate the international donor bureaucracy. However, another way to look at the problem would be that donors do not have the capacity to meet local aid groups where they are. Donors are not staffed to manage more grants of smaller values, such that they can be absorbed by Ukrainian civil society.

For example, USAID’s own stated goal of getting more funding to L/NNGOs remains heavily constrained by a lack of contracting officers. Globally, the agency only has the equivalent of four and a half full-time contracting officers overseeing billions of taxpayer funds managed by BHA. According to a September 9, 2022, letter from U.S. Republican Senators, “Repeated, bipartisan calls for the Department of State and USAID to onboard new nongovernmental organization partners, fast-track the delivery of food aid, and augment BHA’s contracting capacity have remained unanswered.” As one former senior USAID official explained further, most of USAID’s large U.S. partners “saw stable or increased funding over the period 2018 to 2022. This is not what you would expect to see if localization was taking hold… If the U.S. government were truly determined to localize its programs it would create the administrative and management systems necessary to do so.”

Second, most large bilateral donor agencies and their legislative oversight bodies repeatedly emphasize concerns over potential future aid diversion and corruption. By only granting to INGOs and UN agencies, bilateral donors believe that they can insulate the humanitarian response from domestic political concerns over aid diversion. However, these concerns are not unique to Ukraine – they are a common donor excuse for lack of localization progress everywhere. If anything, this rationale should be harder to sustain in Ukraine than in other countries, given that most of these same donors are accepting high risks in their aid to Ukraine’s war effort.

A third barrier to localization in Ukraine is the high degree of mixing of military and civilian aid. The most powerful donors,15 INGOs and UN agencies in Ukraine are guided by core humanitarian principles of independence, neutrality, and impartiality.16 On the other hand, many Ukrainian groups view their relief efforts as part of a whole-of-society resistance to the Russian invasion. For them, the distinction between aid for soldiers versus civilians does not carry the same significance.

The potential for friction over this crucial issue seems to be growing. Ukrainians are increasingly aware of international commitment to principled aid. And some L/NNGOs have moved from a mixed aid response to exclusively targeting civilian populations for aid. However, international aid workers report that aid mixing continues, especially in frontline areas and across some local coordination platforms. This is likely to lead to serious ruptures in partnerships at some point in the future.

The Way Forward

These three main barriers to localization present significant challenges to both Ukrainian and international humanitarian actors seeking to reform the aid system. But they are not insurmountable. As a first step, donors should be substantially located inside Ukraine and engage a wide range of different L/NNGOs in regular discussions about their priorities. Donors should then work with their lead international partners and grantees to mandate change. Donors should ensure that volunteer networks, women-led organizations, and organizations serving marginalized populations are heard in these conversations alongside other L/NNGOs.

At a minimum and based on Ukrainian views expressed repeatedly over the course of the response, donors should mandate that implementing partners take four key steps. First, UN agencies and international NGOs should commit to equitable partnership and ethical hiring guidelines (see footnotes 2 and 7 above), with clear targets for overheads,17 duty-of-care provisions, and fair employment practices. Second, these international organizations should track and report on progress toward meeting these targets. This includes data and benchmarks on the amount of funding that has been passed through to sub-grantees.

Third, international aid organizations working with third-party monitors should partner with local groups and build the latter’s capacity so that Ukrainians can take over responsibility for monitoring the aid effort.

Finally, donors and aid organizations should better publicize funding opportunities, partnership principles, and opportunities to engage international coordination structures, especially in local languages. Importantly, the definition of local should not include the locally established partners of international organizations if that locally established partner does not have a strong degree of independence and local embeddedness, especially when it comes to being able to make strategic and financial decisions.

For their part, UN agencies and INGOs should lead by example and drive change within their own organizations on localization commitments. This means moving beyond aspirational objectives and developing concrete localization strategies. These strategies should set out specific targets and benchmarks to steadily move control of funding and programs as much as possible to L/NNGOs. International organizations should review ongoing programs and partnerships in order to see where barriers to localization (e.g. the passporting of vetting procedures and overly burdensome requirements) might finally be addressed. These strategies should hold INGOs and UN agencies accountable to clearly defined equitable partnership and ethical hiring guidelines in line with the Grand Bargain.

Next, donors, especially DG-ECHO and USAID, should invest more in the UHF, contingent on localization reforms. As it currently stands, DG ECHO does not provide any funding to the UHF,18 while USAID provides only a relatively small amount ($20 million). More funding, alongside strongly encouraging the UHF to award more support to Ukrainian organizations, is in line with both agencies’ stated goals on localization. The UHF should examine the possibility of issuing specific funding calls or “envelopes” that would address the key barriers to localization.

For example, a human resources envelope could support L/NNGOs to hire Ukrainians for three key positions generally viewed as crucial for any humanitarian organization to grow and sustain itself: a Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL) officer, a partnership officer, and a grants officer. This triad would help local groups to better manage INGO partnerships and become prime grantees and/or UHF recipients. These posts would help Ukrainian organizations become more sustainable over time. However, this envelope should be flexible and allow Ukrainians to request support for other human resource priorities in their organizations. Ideally, this envelope would be multi-year.

A second envelope could support anti-corruption systems embedded inside Ukrainian organizations as well as joint NNGO-INGO third-party monitoring. Funding anti-corruption systems within Ukrainian L/NNGOs would strengthen L/NNGO’s own internal capacities. It could also have a positive multiplier effect by further fortifying Ukrainian society against aid diversion and corruption generally.

A third envelope could provide support for Ukrainian organizations willing to separate humanitarian operations from the military effort. A significant number of L/NNGOs remain adamant that they will never separate or end their support for the military. However, other Ukrainian groups have expressed a willingness to do so if the marginal costs and technical challenges associated with creating a firewall for their activities could be covered. It should be noted that even if such an admittedly challenging program could be successfully realized, it remains unclear whether donors and international humanitarian agencies would accept firewalling as a solution.

A final envelope would support Ukrainian-led humanitarian coordination platforms and deepen meaningful Ukrainian engagement in internationally led coordination mechanisms. For example, this envelope could support Ukrainian coordination platforms that want to participate in the Cluster system. It would also help address somewhat uneven capacity in Ukrainian coordination across oblasts. Several oblasts appear stronger in this regard than others, according to local workshop consultations with whom Refugees International spoke.

The UHF should also consider funding micro-grants for those L/NNGOs that need assistance in applying for UHF funding calls while committing resources towards a robust outreach and communications strategy—in the Ukrainian language. And it should significantly scale up its recent $20 million envelope to support smaller volunteer networks, CSOs, and L/NNGOs and press the Humanitarian Response Plan to allow for funding beyond 6 to 12 months. The UHF should also relax the Cluster attendance requirement for grantees (see footnote 12) at least until the UN makes a concerted effort to promote Ukrainian involvement and leadership in the Clusters.

If the UHF proves unwilling or unable to take the above steps, donors and international NGOs should launch a new Ukraine Country-Based Pool Fund. Donor-vetted INGOs would provide legal, financial, and technical support to fund operations. But they would do so under the leadership and direction of Ukrainian NGOs, which would set priorities and budget allocations. The fund’s main objective would be to rapidly and directly fund Ukrainian organizations engaged in the humanitarian response. But it could also resource the four specific envelopes discussed above to support localization.

The creation of such an NGO-led pooled fund would not be something new in crisis responses. Indeed, there are several existing models that could be built on (or even encouraged for Ukraine if an entirely new, donor-led pool fund proves impossible), including those managed by the NEAR Network, START fund, FCDO/Danish Refugee Council, and others. As ICVA recently noted, “there are a growing number of funds such as these that have prioritized funding to local partners and are often less expensive to operate and more flexible than traditional” UN-led pooled funds.

Crucially, a Ukraine pool fund underpinned by INGOs would help both ECHO and USAID to substantially advance both of their commitments to localization in the near term.19 For USAID especially, it would relieve its own evident lack of human resources in distributing funds directly to Ukrainian organizations since the pool fund administrators would select and oversee grants. And it would maintain the intermediary role currently in place with INGOs and UN agencies that is perceived as politically necessary in the current climate.

On coordination, UN-led mechanisms such as the HCT and the Cluster system should set out near-term timelines for increasing Ukrainian participation and leadership.20 The UN, specifically, should insist that Ukrainian organizations fill the majority of NGO seats at the HCT coordination table. In the Cluster system, UN agencies should actively seek and require that L/NNGO staff take on cluster co-lead roles, as was done in South Sudan. And all UN entities should widely publicize in Ukrainian the role and responsibilities of the Cluster system and other internationally led coordination mechanisms, as well as offer a clear explanation of how to engage. For its part, the new NGO Platform bringing together INGOs and L/NNGOs should ensure that a comprehensive set of localization principles are agreed upon by all member organizations as a prerequisite for joining.21

However, the best way to solve the coordination disconnect would be for international actors to engage and invest in the multitude of Ukrainian-led coordination mechanisms that have expanded over the last year, some of which are detailed in the textbox above. As a December 8 private briefing note from ICVA concluded, one of the main goals should not only be greater representation or leadership by Ukrainians in the Clusters, i.e. “bringing them into the system.” Instead, international actors should adapt themselves to Ukrainian structures in order “to sustainably add value and improve quality in such a large, complex response.”

Conclusion

Despite the time that has been lost, it is not too late for fundamental changes in the response to improve the overall humanitarian outlook in the months and years ahead. There are still billions of dollars more in humanitarian funding that will probably make its way to Ukraine (having been pledged last year) or serve as new funding no matter the political challenges that may arise over allied support in 2023. Some of these funds should be immediately marshaled in the service of the specific localization reforms that can improve the sustainability and reach of the overall response. Ukrainian capacities also appear to be growing steadily, as is Ukrainian awareness about what should be done differently when it comes to the response in their own country. The humanitarian response in Ukraine can and should set a strong precedent for change – one that can be leveraged globally to the benefit of all of those in need.

Endnotes

[1] The aid community has developed an extensive set of agreements, platforms, and best practices when it comes to localizing aid—most notably the 2016 Grand Bargain which commits INGOS, UN agencies, and donors to provide 25 percent of global humanitarian funding to local actors while centering and empowering them in the humanitarian system.

Ukrainians need greater control over international aid flowing into their country. Leaving them out is not just a missed opportunity—it severely undercuts the effectiveness of the aid effort.[2] Equitable partnership draft proposals have been put forward by a number of organizations in Ukraine. Most commonly they call for mandating fair overhead cost recovery for all sub-grantees, substantive involvement in program design, as well as a number of other provisions laid out in detail by the Grand Bargain.

[3] As of December 2022, OCHA reports that more than half of humanitarian organizations are focusing their response on food assistance and livelihood support. Almost 200 partners have provided services related to health to 9.2 million people since the start of the war, ensuring that people have access to essential health care across the country. Some 160 partners have been working to provide shelter kits, beds and supporting items, heating solutions, building materials, and various sorts of repairs to those who lost their homes or have been internally displaced, especially with repairs and essential items during the cold weather and heavy snow. Since the start of the war, they have reached more than 2.7 million people.

[4] According to the 2023 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO), “Since 10 October 2022, systematic attacks on Ukraine’s national power grid have caused severe damage to critical infrastructure, impacting electricity, heating, and water as outside temperatures fall. According to the Government of Ukraine, some 30-40 percent of the country’s power infrastructure was damaged or destroyed within the first 10 days of the escalation.”

[5] USAID has committed to providing “at least a quarter of our program funds directly to local partners by the end of FY 2025. And by 2030, fifty percent of our programming will place local communities in the lead to set priorities, codesign projects, drive implementation, or evaluate the impact of our programs… We will also improve how we track subawards to local actors.”

[6] As of January 20, 2023, the UHF had received donor contributions totaling $327 million, although actual allocations throughout 2022 reached $192 million i.e. less than the annual allocations in Afghanistan ($273 million), which is the second largest UN CBPF in the world in terms of contributions.

[7] Ethical hiring or Ethical Recruitment Guidelines have been tabled at the HCT and generally aim to prevent poaching high-capacity staff from local NGOs (thereby undermining their capacity to respond) and make attempts to keep salaries and benefits within as close a range as possible to local actors.

[8] It is important to note that the amount included in L/NNGO allocations counts some contributions made by the UHF to L/NNGOs as well as a $44 million grant from the government of Austria to one of its own L/NNGOs, Nachbar in Not, making it likely that the actual dollar amount directly granted to L/NNGOs is closer to 0 percent.

[9] As the International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA) put it in response to a call for feedback in the fall of 2022 from ECHO, the agency should be ensuring that it “includes markers to track direct allocations to local partners and funding that intermediaries have committed to transfer to local partners as part of approved funding agreements…”

[10] See the private briefing note, “Support to Strengthen the NGO and Interagency Response in Ukraine

ICVA Mission Report,” December 8, 2022 (available upon request).

[11] See the DEC Scoping Survey as well as Refugees International’s “Localizing Aid in Ukraine: Perspectives from Ukrainian Humanitarians in Odesa, Lviv, Zaporizhia, Dnipro, and Chernihiv.”

[12] There is at least one practical cost imposed on L/NNGOs by the international aid system for the lack of involvement in international coordination mechanisms. A requirement for receiving UHF funds is engagement in the Cluster System, the primary coordination vehicle headed by UN agencies and focused on the various humanitarian response sectors. Since Ukrainian participation in the Clusters has been low, most L/NNGOs have approached the different UHF funding rounds only to find themselves immediately disqualified.

[13] Examples include https://t.me/VolunteerCountry and chat @VolunteerTalks, https://t.me/logistikavolonter, and https://t.me/humanitarna.

[14] For example, the central government created a platform for Ukrainians who can host Ukrainians in Ukraine or abroad. The site also hosts a compensation mechanism from the government. There are also several volunteer platforms including palyanytsya.info and other livelihood opportunity platforms like https://makeitwithukraine.org.

[15] USAID’s October draft Report on Localization stresses that, “The internationally recognized humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence underpin BHA’s humanitarian assistance…As BHA works to strengthen and sustain partnerships with local actors, it will undertake careful analysis and adopt context-appropriate modalities that do not compromise humanitarian principles…”

[16] For one recent analysis of differences over the meaning of principled humanitarian action, and especially “resistance humanitarianism,” see especially: “The principles debate just woke up: now where’s the evidence about the practice?”

[17] According to a former senior USAID official, most local organizations across USAID-funded programs are limited to a 10 percent overhead rate while international partners earn 20 to 40 percent through their negotiated indirect cost agreements. “These rates and previous studies make clear that the costs of implementing U.S. government programs far exceed 10 percent… As a bureaucratic innovator, USAID should be able to devise an equitable way for local organizations to recover the full cost of doing business with the U.S. government.”

[18] An alternative entry point for direct funding of L/NNGOs by the European Union potentially lies with DG NEAR since it has recently started funding some Ukrainian L/NNGOs who transitioned into humanitarian aid provision.

[19] As USAID put it in its October 2022 Draft Report, among several beneficial aspects, pool funds “serve as a mechanism to provide funding to local actors who are not yet able to become direct USAID partners.”

[20] The NGO Platform as well as the UN system as a whole should also consider that Ukraine may offer an opportunity to transition to a different Area Based Coordination system, perhaps founded around the central role of oblasts. As one report from the Center for Global Development put it, such an approach would, “treat needs holistically within a defined community or geography; provide aid that is explicitly multisector and multidisciplinary; and design and implement assistance through participatory engagement with affected communities and leaders. Integrating these elements of area-based logic into the humanitarian coordination architecture would better align humanitarian action around the expressed needs and aspirations of crisis-affected people.” As ICVA points out, although there has been much discussion of the potential for piloting Area-Based Coordination approaches, “the discussions seem to be stuck between theory and practice.”

[21] Specific steps to strengthen the participation and leadership of local and national actors in coordination mechanisms are laid out in detail in recently updated IASC guidance.

Banner Photo Caption: Local residents receive food aid following a Sunday service at a Pentecostal church on February 19, 2023 in Kramatorsk, Ukraine. Photo by John Moore via Getty Images.