This Syrian Refugee Graffiti Artist Has a Message for the World

Haleem Kawa, a Syrian refugee living in Turkey, has a message for the world: Idlib needs your help.

Kawa helps run the graffiti collective “Banksy Syria,” fondly named after the British street artist known for his political messages. Their art, painted on walls in Syria’s besieged Idlib province and then posted on social media, calls for solidarity and support from the world amid a bloody military campaign waged by the Syrian regime and its Russian ally to retake the territory.

“The main messages you hear in media are just about war and killing. No one hears the voices of people.”

“Our goals are to transfer the voice of people inside Syria abroad,” Kawa explains from a café in Gaziantep in southern Turkey. “The main messages you hear in media are just about war and killing. No one hears the voices of people. We want to raise their voices and show the world what these people believe in—freedom, dignity—and to put a spotlight on how the government is not giving these rights to people.”

Banksy Syria started in early 2019, just as the military offensive in Idlib began to intensify after a ceasefire deal brokered in September the previous year fell apart. In the last two months alone, more than 540 civilians have been killed, thousands injured, and 330,000 people displaced by the military campaign, according to conservative estimates by the UN. Russian airstrikes have destroyed schools, hospitals, and other civilian sites, and regime forces are reportedly burning crops in the area now that it is harvest time. Penned in by regime-controlled territory and a closed border with Turkey to the north, people in Idlib have nowhere to turn. The province is “on the brink of a humanitarian nightmare unlike anything we have seen this century,” according to the UN.

Banksy Syria wants the world to know what is happening to Idlib. The collective is made up of ten volunteers inside Syria. Kawa and a team of organizers, working with the Syrian NGO Kesh Malik (or Checkmate), get together to think of new designs and workshop the pieces, then volunteers inside Idlib set to painting. Their art appears mostly in English and uses icons and ideas the team feels will resonate with the West.

“Western people and governments are our main audience,” Kawa said. “They are the only people who can change what’s happening in Syria.”

One piece features Marie Colvin, the American journalist killed in a regime airstrike in Homs in 2012, and the famous words of her final broadcast from Syria just minutes before her death: “The words on everybody’s lips here are: Why have we been abandoned?”

Another playfully reaches out to “Egg Boy,” the Australian teen who smashed an egg on the head of a far-right politician on camera.

Yet another plays off of the hit TV show Game of Thrones.

Kawa says a recent piece featuring the viral image of Sudanese women’s rights activist Hala Al-Karib has been particularly popular inside Idlib. People flock to take selfies with the art.

Kawa has used graffiti as a form of resistance since the early days of the Syrian revolution—which started off in response to the arrests and brutal torture of two boys in Deraa, Syria for drawing anti-regime graffiti on a school in 2011. He was a university student in Aleppo at the time, and shortly after joining the protests, he found himself stenciling his own messages on city walls about freedom and human rights.

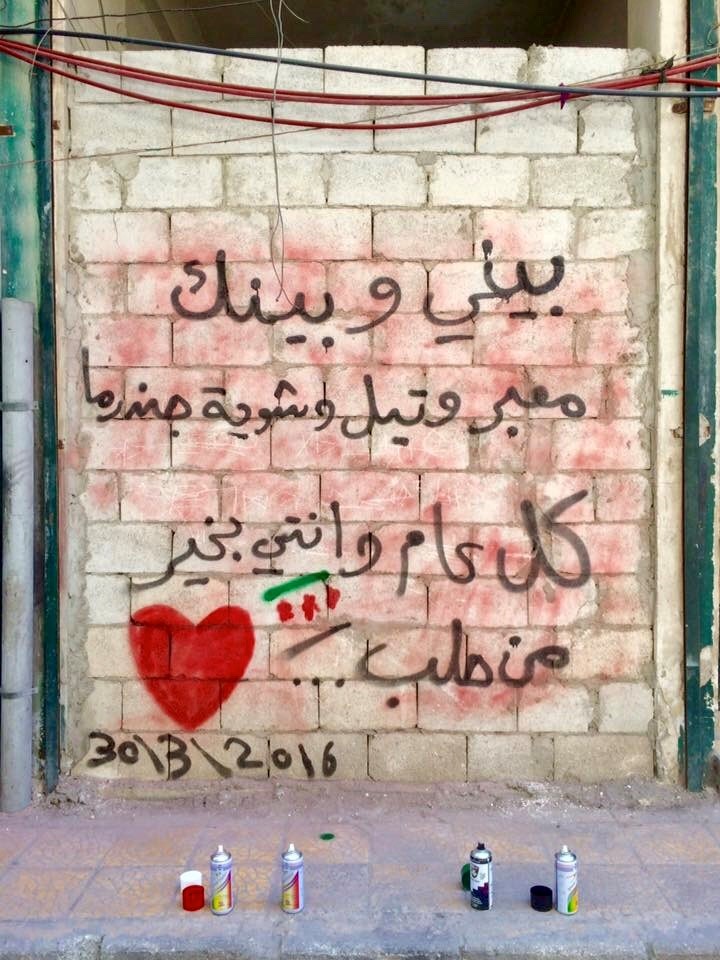

He used graffiti to send personal messages during the war too. In 2016, after his girlfriend fled with her family to Turkey, he had few means and little money to celebrate her birthday while he remained in Aleppo. He took to what he knew best.

“Between you and me is just a border crossing, wires, and a few soldiers. Happy birthday from Aleppo,” the graffiti reads. Happily, the message may have worked—the two are now married and live in Turkey with their child.

Kawa says Banksy Syria will continue their work despite the constant threat of violence in Idlib. They want their message to break through—and to show that the world that civilians inside Idlib, including groups like the Syrian Civil Defense, are doing what they can to help each other survive.

“We want the world to know the scale of the crimes and the pain inside Idlib and to know that the civilians are not the same as the terror organizations,” said Kawa. “The solution is not shelling and bombing…. There are so many civilians inside Idlib who are against what’s going on. There are people resisting.”