Complex Road to Recovery: COVID-19, Cyclone Amphan, Monsoon Flooding Collide in Bangladesh and India

The Costliest Disaster Ever to Have Impacted the Bay of Bengal

On the morning of May 20, 2020, Tropical Cyclone Amphan (“Amphan”) slammed into India and Bangladesh. It made landfall first in the eastern Indian states of West Bengal and Odisha, lashing them with wind speeds of up to 210 km/h. Nearly 60 million people across India felt Amphan’s effects—in which at least 95 people lost their lives, hundreds of thousands had to be evacuated to temporary shelters, and more than 2.9 million homes were damaged or destroyed. The storm washed away about 1.7 million hectares of productive cropland and aquaculture farms and killed 2.1 million animals.

In India, Amphan was calculated to be the costliest disaster ever to have impacted the Bay of Bengal, with $13.2 billion worth of damages. The Sundarbans, a collection of deltaic islands that straddle the India-Bangladesh border and is home to more than 4 million people, was hit particularly hard. The area was the first to be struck by the cyclone at the height of its strength before it swept northeast towards Kolkata, where it was downgraded to a tropical depression. According to Chief Minister of West Bengal Mamata Banerjee, Amphan destroyed over 28 percent of the Sundarbans in one fell swoop. In addition, it damaged more than a quarter of the area’s mangrove forests, the habitat of the iconic Bengal tiger and first line of defense against storms for the region and the city of Kolkata.

In Bangladesh, where the storm further weakened as it made its way over land, more than 55,600 homes were completely destroyed, and at least 162,000 homes were partially damaged. Amphan displaced over 100,000 people—with more than half still sheltering on embankments or with friends and relatives at the end of May. As of July 15, 2020, there were 6,000 people still in shelters, and 50,000 people in need of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and livelihood and basic needs support. While national authorities are still measuring the total cost of destruction, early reports estimate damage at $130 million, which includes impacts on electricity grids, schools, bridges, embankments, roads, drinking water sources, and local administration and community infrastructures. The amount of damage in absolute terms may pale in comparison to that in India, but the need for humanitarian assistance and support from the international community is much greater in Bangladesh. Unprecedented monsoon flooding in June brought additional appeals for assistance. However, to date, both climate-influenced disasters remain sorely underfunded.

In India and Bangladesh, COVID-19, Amphan, and monsoon flooding have collided to create complex crises. COVID-19 has left both countries’ economies reeling. These effects have been felt most acutely by those working in the informal sector and in cities, which were brought to a halt by lockdowns. Migrant workers were especially affected. Due to COVID-19, these workers returned home to seek safety and shelter just weeks before Amphan hit. Those returning to regions impacted by Amphan were not only exposed to the cyclone, but were also deprived of the chance to send remittances from their former places of employment to help their families rebuild. COVID-19 has also made it very difficult to provide basic services, such as evacuation and shelters, in the face of natural hazards.

In addition, Amphan will have long-lasting impacts on coastal communities’ livelihoods, as the storm surge has salinized large swaths of cropland, rendering them unusable for years to come. Rural, coastal communities dependent on agricultural have been hit particularly hard. Migrant workers who have returned to these communities will find it harder than ever to make a livelihood back home, but COVID-19 makes it unlikely they will be able to return quickly and safely to their old jobs in the cities.

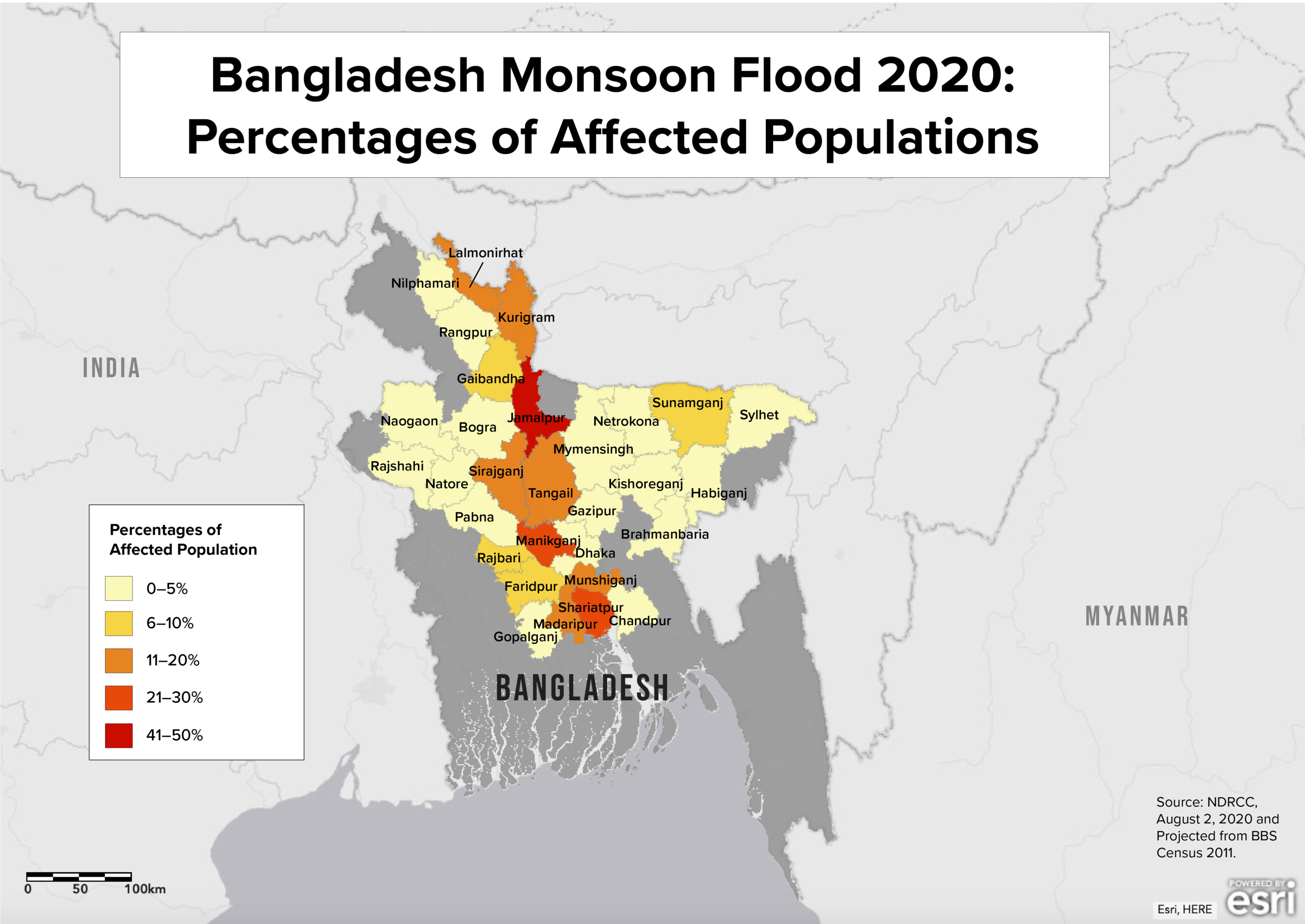

In Bangladesh, unprecedented monsoon flooding, which began in June, has made it even harder to recover. To date, almost 890,000 Bangladeshis have been displaced and more than a million homes inundated. Owing in large measure to climate change, the frequency of these formerly once-in-a-lifetime events will only increase into the future.

The experience of Bangladesh and India reveals an uncomfortable truth: complex and multifaceted disasters are the way of the future and, therefore, require a multifaceted set of responses. Recovery will depend on immediate humanitarian and economic assistance, longer-term investment in climate change adaptation and resilience programming, and coming to terms with the fact that these types of measures may have limits and planned relocation may be a necessary policy option. Recovery will also mean targeting those who are most disproportionally affected by this crisis, including the rural poor and migrant workers. The international humanitarian and development community must step up. National and local governments must ensure that the most vulnerable communities are provided adequate access and amounts of economic and social assistance to support a sustainable recovery.

COVID-19 Complicates Evacuation, Shelter Provision, and Recovery

India

Even before Amphan hit, India had the third highest number of total coronavirus cases in the world. West Bengal was designated a “red zone” due to steadily increasing cases of COVID-19. Despite these risks, local governments preemptively evacuated over 700,000 inhabitants, instructing evacuees to maintain social distancing and other prevention measures. Cyclone shelters also had to be COVID-proofed. For example, shelters in West Bengal normally capable of housing 500,000 people could only shelter 200,000 in order to enforce social distancing.

Valid fears and confusion among local people also posed challenges, both during the evacuation and with subsequent relief efforts. For example, families afraid of getting sick fled cyclone shelters as soon as they could. Some villages refused aid deliveries for fear that they were infected with the virus. Two weeks after Amphan hit, the number of coronavirus cases in West Bengal increased to more than 5,500 from 3,103, and the number of deaths from the virus from 181 to 300. It is unclear what role tight quarters in shelters may have played, however.

Just months after the storm, India leads all other countries in the number of new COVID-19 cases recorded per day. The month of August saw 70,000 newly infected people—or about one-fourth of all new worldwide cases. Even worse, India’s cases may be severely under-recorded. According to Indian economist Jean Dreze, this could mean that the official count of 2.5 million may be closer to 5 million. As the number of infected continues to spread, evacuation and shelter provision for any future disasters will be even more complicated.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, national authorities ordered the evacuation of 2.4 million people. More than 12,000 shelters and public infrastructure, such as schools, were prepared for evacuees—three times as many than in previous years. In order to deal with COVID risk, all shelters were equipped with masks, sanitizers, and handwashing facilities with soap, and health clinics were prepped in advance to isolate any evacuees exhibiting symptoms.

Bangladesh continues to face a multitude of challenges in addressing COVID-19 post-Amphan, including a very dense population and limited health infrastructure. To date, it has recorded almost 275,000 confirmed cases and more than 3,600 deaths. However, concerns remain over the high cost of testing, low trust in the healthcare sector in general, and a limited testing regime based primarily out of Dhaka. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the country needs about $250 million for clinical equipment, testing, and contact tracing from external funders just to respond to initial impacts.

Economic Recovery

COVID-19 has also shaken the economies of Bangladesh and India to their core. For example, India’s gross domestic product is expected to contract by at least 5 percent for the year; and Bangladesh’s GDP by 6 percent. These impacts have been largely driven by drops in domestic activity and spikes in unemployment. In addition, India’s industrial production dropped sharply at the start of lockdown, and its service sector saw its largest month-to-month contraction. In Bangladesh, overall exports fell by more than 83 percent in April, and remittances from Bangladeshis abroad fell dramatically. Therefore, both countries will also need a rapid infusion of economic stimuli to be able to sustain economic activity, especially for the poor and those in the informal sector.

Double Disaster for Migrant Workers

In both India and Bangladesh, many migrant workers and their families have suffered a “double disaster” or worse, due to COVID-19 and disaster resulting from natural hazards.

India

In India, COVID-19 and the lockdown ordered by India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi on March 25, 2020, put migrant workers from rural regions in harm’s way, both physically and economically. The lockdown left many migrant workers, which make up nearly one-fifth of the country’s workforce, in an economic bind. Without access to cash or government support, they were forced to return home. In some instances, they walked hundreds or thousands of miles to get back without government assistance. More than 1 million migrant workers returned to West Bengal alone. Many migrant workers have come back “jobless and penniless,” a local NGO worker told Refugees International on July 1. “Many people are hungry….and there is not too much money in bank accounts,” he said.

Their return was ill-timed, as Cyclone Amphan hit less than a month later. This meant more villagers were exposed to the storm and families had even fewer resources to recover. “Many people would rebuild after cyclones by going out to work and sending remittances back home. [But now] men and women who want to rebuild their lives do not have the opportunity to do so since there’s no out-migration,” an independent researcher told Refugees International in June.

Return home has also complicated migrant workers’ ability to access myriad economic support schemes, including a $277 billion support package announced on May 18, which promises credit to farmers, cash transfers to the poor, and access to food security programs. Not-fit-for-purpose policies and bureaucratic hurdles are largely to blame for this lack of access. For example, access to many support schemes requires registration in the state in which migrants work. But, now, migrant workers are no longer living in the state where registration was issued. In addition, migrant workers have limited access to bank accounts, where direct cash transfers from these schemes are often deposited.

Leaving out migrant workers who have been forced to return home and their families from support programs could have disastrous implications, as Amphan has taken a toll on already precarious agricultural livelihoods.

One Congress Party MP from a town in Bihar, India, reflected this concern in a comment to The Wire: I am really concerned about the agricultural prospects in the coming year, as almost 80-90 percent of farmland in my constituency is submerged in saline water [due to the storm].

Amphan affected large parts of coastal communities with saltwater intrusion, according to agronomist K Sarangi of the ICAR-Central Soil Salinity Research Institute. “Trees and standing crops were destroyed, livestock dead, livelihoods affected and infrastructure such as irrigation etc….hit hard,” he told reporters. He also estimates that productive agricultural land has decreased by 50 percent in the region and that cultivation of pulses will be set back by at least five years.

The day after Amphan made landfall, the government of India announced a $132 million relief package for those affected by the storm. The state of West Bengal also announced $827,000 in aid for rebuilding houses, helping farmers, and repairing wells in the Sundarbans.

Belatedly, Prime Minister Modi also launched an employment scheme for migrant workers on June 20, which is separate and apart from the economic support package launched in May. The scheme seeks to contract migrant workers to help build local infrastructure projects, including housing, plantations, drinking water fountains, community toilets, roads, and cattle sheds, among others. However, the scheme will last only 125 days and applies to only 116 districts in six states. West Bengal, the site of much Amphan destruction, is not one of the designated states.

Bangladesh

Migrant workers in Bangladesh have experienced similar challenges. While migrant workers from urban centers such as Dhaka, Chittagong, Narayanganj, and Gazipur, have returned home to the rural countryside by the tens of thousands, the most vulnerable Bangladeshi migrant workers are returning home from abroad. Since April, more than 127,000 migrant workers have returned from 28 countries, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Maldives, Iraq, Qatar, Malaysia, and Singapore, among others. “For many of these migrants, it isn’t a happy homecoming as they have lost their source of income and due to the global recession it is unlikely that they will be able to return to work abroad until the global [labor] market recovers from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic,” said IOM Bangladesh’s Chief of Mission Giorgi Gigauri.

In September, Imran Ahmad, the Expatriates’ Welfare Minister, told parliament that more than $15 million has been provided to Bangladeshi migrant workers abroad to deal with the crisis. In addition, initiatives in Bangladesh have been put into place for migrant worker reintegration, including specialized training and facilitation of re-employment. The government of Bangladesh announced a low-interest rate loan package of $58.9 million for Bangladeshi expatriates who lost jobs during the pandemic to support employment-generating activities. The Expatriates’ Welfare Ministry also created a separate $25.5 million fund for returnees and families of those who died from COVID-19 while working abroad. Despite these measures, more than 70 percent of returned migrant workers remained unemployed by mid-August. Prospects look bleak in the face of a global economic recession, Amphan, and monsoon flooding impacts to agricultural livelihoods back home.

While these economic initiatives are meant to dampen negative economic impacts from a sharp decrease in remittances—a 22 percent drop in Bangladesh, or over $4 billion, according to the World Bank—they are one-dimensional in scope. In order to ensure migrant workers’ needs are fully met, access to testing and healthcare must be prioritized alongside economic recovery. Medical assistance should be provided even before return, with testing for COVID-19 provided while abroad and upon return. COVID testing should also be provided either free of charge or at least lower than the current price of testing, $1.18 per test, which experts consider a barrier for the poor.

A concerted effort to invest in the health of migrant workers will also aid in defending against stigmatization and discrimination that they face back home. Rural villagers still largely believe that COVID-19 is a “foreign” disease and that those that have worked abroad (or even in cities) are the source of the virus. This was further exacerbated by the government of Bangladesh (GOB) itself, with the minister of health urging migrant workers not to return in March. The GOB must not feed into these fears, but instead must actively combat them. Mass testing of migrant workers will, therefore, accomplish two things: (i) identify and quarantine infected migrant workers to prevent the spread of the virus; and (ii) allow those that are COVID-free to travel more freely and pursue economic opportunities outside of their home villages without stigma.

International Humanitarian Assistance Still Needed in Bangladesh

While the government of India and local authorities are managing Amphan recovery without significant engagement from international organizations and limited funding support, Bangladesh has turned to the international humanitarian community for coordination and funding. The country’s Humanitarian Coordination Task Team (HCTT) put together a comprehensive response plan, with assessments of the needs of food security, nutrition, shelter, WASH, gender-based violence, and child protection sectors. A May 31, 2020 post-impact survey of the most affected areas of the country found that more than 60 percent of impacted “unions,” or local communities, reported a “severe need for assistance.” The district of Satkhira in southwestern Bangladesh, which lies on the border with India’s Sundarbans, reported over 75 percent of their unions in serious need of assistance. Respondents in 99 percent of unions also said that the cyclone had badly affected people’s livelihoods.

Given the scope of the impact, most local communities are still requesting in-kind food support, cash assistance and livelihood support, housing repair and reconstruction, and WASH and infrastructure support. In total, the HCTT humanitarian response plan requests $25 million in funding to support over 700,000 people in 7 different affected districts to address these needs. However, by June 22, 2020, the plan had received $6.5 million, or only 26 percent of the total requested.

The Bangladesh Red Crescent Society (BDRCS) noted in their July 10 operations report that their appeals had only received 13 percent in hard pledges and they have had to cut back on provision of services, including limiting their support to providing shelter, technical support, improved access to medical treatment, and provision of WASH services.

Floods Leave Bangladesh in Additional Bind

As Bangladesh was in the throes of recovering from Amphan, the monsoon season brought unprecedented flooding in June. Extreme rain left a third of the country inundated—the worst impacts seen in a decade and the longest lasting flooding since 1988. “It’s like a double whammy. In our case, it’s a triple whammy [with COVID-19],” Saleemul Huq, the director of International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD), told Refugees International in August.

Impacts from the floods have been devastating. Bangladeshi officials report that more than 5.5 million people have been affected. Almost 890,000 people have been displaced, with 94,414 people evacuated into 1,525 shelters as of September 5. The floods also submerged over a million homes and damaged more than 1,500 sq. km. of farmland. According to HCTT assessments, the floods combined with the impacts of COVID-19 have significantly hampered economic livelihoods for 90 percent of unions surveyed, with 62 percent of total respondents reporting the need for food assistance. More than 80 percent of unions surveyed also found families skipping daily meals or significantly lowering their food intake.

The September 5, 2020 HCTT response plan requests $40 million to support over 1 million people recover from the floods in seven of the most affected districts in the country. A funding gap of over $34 million (or over 86 percent) remains. Progress on funding for child protection and food security is substantial; however, significant shortfalls remain for nutrition, WASH, and integrated GBV and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) sectors.

Climate-Related Disaster and Planned Relocation

Cyclone Amphan and extreme flooding are a harbinger of things to come. According to the India Meteorological Department, the Bay of Bengal has seen a 26 percent rise in the frequency of high to very high intensity cyclones over the last 120 years. West Bengal Sundarbans Affairs Minister Manturam Pakhira noted that storms are becoming stronger and stronger: “[2009’s Cyclone] Aila’s wind speed was 110 km/h, [2019’s Cyclone] Bulbul was 130 km/h, but Amphan was 220 km/h.”

The rise in frequency and intensity of cyclones can be linked in part to climatic changes in the Bay of Bengal. Climate scientist Roxy Mathew Koll of the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology noted that some of the highest surface temperatures were recorded by weather buoys installed in the Bay of Bengal, with unprecedented values of 32-34 degrees Celsius, just before the cyclone. This rise in surface temperature created the perfect conditions for the storm’s wind speed to grow exponentially: “in about 18 hours it developed from a Category 1 to a Category 5 storm with winds of up to 250 km/h,” he said.

Both sea-level rise and repeated storm surge make it hard to imagine agriculture remaining productive on the countries’ coasts. “Salinity is the worst long-term impact. Once the saltwater goes into the land, it makes it useless for several years. During Cyclone Sidr and Aila, people evacuated and have [effectively] become refugees because land has become so salinized…and sea-level rise is a compounding factor,” Huq told Refugees International in August. In the Sundarbans, the sea-level is also rising faster than in other areas of the world.

In Bangladesh, extreme flooding during the monsoon season has also become the new normal. Huq told Refugees International that— A severe flood is a one-and-20-year flood. Over the last several hundred years of recordkeeping, a one-in-20-year flood has happened every year in the last four years, and this one may be categorized as the fifth. This type of intensity can be attributed to human-induced climate change. [Climate models] predict the hydrological pattern of the monsoon season will shift significantly, with more rainfall during the monsoon, and less during the dry season.

Given these hazards, there has been a growing movement to resettle villagers outside of “at-risk” areas on the coasts. In the case of India, researchers with the Kolkata’s Observer Research Foundation suggest “retreat legislation” that may be used to identify and preemptively resettle villagers at-risk for sea-level rise and coastal erosion. The legislation would also “prevent the sale, transfer, reconstruction and bequeathing of existing properties in at-risk locations.” However, planned relocation often involves complex social, political, and psychological issues, including fairness of compensation, land rights, and loss of traditional livelihoods.

As one independent researcher told Refugees International on June 19: “Why is it we think of moving the weakest, poorest, most precarious instead of thinking about moving people who live in Kolkata who have the means to move? Displacement ends up falling on people whose lives are disposable.”

It is almost certainly the case that planned relocation must be part of disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation strategies. But it is essential there be an inclusive consultative process with communities to enable fair and just pathways going forward.

Conclusion and Recommendations

COVID-19, Cyclone Amphan, and monsoon flooding have shown us what a multifaceted and complex series of disasters look like today—and likely in the future. Our reporting finds that vulnerable communities living on the margins in Bangladesh and India are subject to some of the worst impacts. In particular, it finds that poor, rural communities dependent on agriculture and migrant workers that often leave these communities to find a better life may be hardest hit. Sound, fact-based national policies today may help these groups recover faster. International humanitarian assistance will ensure that those displaced and economically down-and-out do not fall further in between the cracks.

Donor states must:

- Fulfill humanitarian obligations and heed the call for humanitarian assistance in Bangladesh. Cyclone Amphan is the costliest disaster in the history of the Bay of Bengal. Despite this, humanitarian appeals continue to be underfunded. Bangladesh’s HCTT’s humanitarian Amphan response plan appeal of $25 million is only 26 percent funded. The HCTT monsoon flooding response plan which requests $40 million has a funding gap of over $34 million, or 86 percent. While rapid short-term food assistance has been relatively successful, long-term food security and livelihood assistance have been limited and underfunded. Shortfalls have also been reported for nutrition, WASH, and integrated GBV and sexual and reproductive health sectors.

The government of India (GOI) must:

- Facilitate migrant worker access to economic assistance. Migrant workers are finding it difficult to access existing economic assistance schemes because of minor bureaucratic hurdles, including shifting states of registration and coordination and coverage issues related to that registration. The GOI must continue to support and explore an integrated and mobile registration system so that migrant workers may access economic, social, and food assistance schemes regardless of their location.

- Enhance and extend migrant worker employment support schemes for long-term recovery. Migrant workers make up more than one-fifth of the country’s workforce and constitute some of the most reliable economic support systems for families recovering from disasters like Cyclone Amphan. It is essential that any employment scheme includes them and targets those most affected by the storm—including the Sundarbans and the state of West Bengal. West Bengal, specifically, should be included in the list of designated states for the migrant worker employment scheme enacted by Prime Minister Modi on June 20, 2020. Extending the number of days guaranteed by the current migrant worker support scheme will also be necessary for long-term recovery.

- Plan for the return of migrant workers to cities and ensure access to hygienic, safe spaces and testing. While migrant workers are already beginning to return to cities as they seek out jobs, the GOI has the opportunity to plan more effectively for returns. COVID-19 programs and policies would be more successful and long-lasting if they were to take into account their needs and provide targeted support. For instance, the GOI must ensure that handwashing stations, soap, face masks, and testing facilities are readily available in migrant communities to ensure that COVID-19 is best managed while re-integrating migrant workers back into the economy.

The government of Bangladesh (GOB) must:

- Prioritize medical assistance and healthcare for migrant workers to ensure their wellbeing and to fight discrimination. Migrant workers will be key to Bangladesh’s economic recovery. While economic assistance is welcome, the GOB must also make a targeted effort to test and provide healthcare resources to migrant workers. Providing free or reduced-cost COVID tests must be a part of this plan.

The governments of India and Bangladesh must:

- Invest in disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation, and resilience measures in communities vulnerable to climate-related disaster. The first order of business for the GOI and GOB is building back better. This includes investing in disaster risk reduction measures, including in cyclone- and storm surge-resistant school, hospitals, and housing. It also means investing in more resilient livelihood options in rural communities. This is especially pressing, as Amphan—and Aila before it—has rendered many paddy fields salinized and unusable for years to come.

- Put into place an inclusive and equitable consultative process to discuss planned relocation. Climate-related disasters are only becoming more frequent and intense. Planned relocation may need to be an option on the table. However, communities must have a say in any decisions over relocation. These decisions must come out of an inclusive, equitable consultative process.

Photo Credit: UNICEF.