COVID-19 and the Other One Percent: An Agenda for the Forcibly Displaced Six Months into the Emergency

Introduction

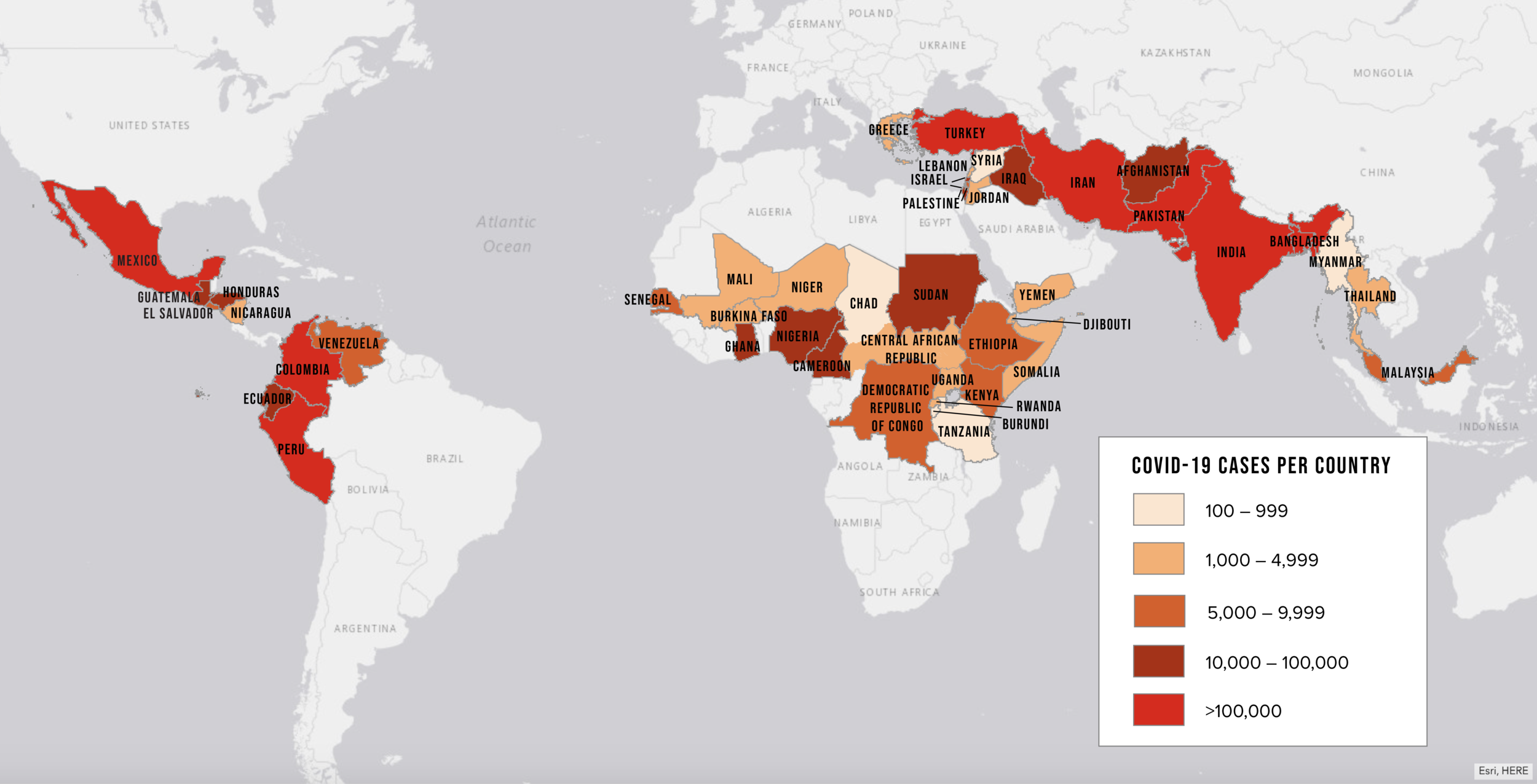

Almost six months after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an international public health emergency, COVID-19 cases globally total more than 13 million. The epicenter has shifted from China and Europe to Latin America, even as the rates of infection in the United States once again spike. Fortunately, some of the world’s most vulnerable populations have so far been spared the worst of the pandemic. However, that is now changing, particularly for those forced from their homes by violence or natural disaster.

There are now more than 79 million refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced people worldwide. Together, they make up almost one percent of the global population. The vast majority come from or reside in low-income countries where COVID-19 infection rates are growing fastest. Humanitarian aid agencies and host governments have been working hard to prevent outbreaks in these communities. But much of this vulnerable other “one percent” will have felt the impact of the pandemic long before the virus arrives.

In March, Refugees International laid out the main factors that make forcibly displaced people so vulnerable to the virus, along with recommendations for key measures to guide the response. Those recommendations have stood the test of time. Nonetheless, over the last three months, the virus has spread in both expected and unanticipated ways. Measures to contain that spread have had enormous and often unintended consequences, particularly for those in need of humanitarian assistance. Drawing on this experience, this brief identifies five key areas of priority to help guide ongoing and future efforts to protect highly vulnerable populations over the next stage of the pandemic.

First, governments and aid agencies should double down on efforts to contain and mitigate the spread of the virus in displaced communities. Early on, there was tremendous concern that refugee and IDP camps would be ravaged by the pandemic. In the event, these communities appear to have received a “golden month” or two to prepare. But now cases have been detected in dozens of camps, including some of the largest, around the world. Essential medical supplies and therapeutics remain in short supply in these settings, as does accurate information about what the displaced can do to protect themselves. In addition, while a vaccine is still many months away, there is very real concern that vaccine nationalism will limit access for the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Second, countries that host large numbers of refugees and IDPs should ensure that these populations are included in their national pandemic response plan. All vulnerable populations should be able to access public services and social welfare programs. This is particularly true for urban refugees and others who live outside camps. The World Bank and other international financial institutions are mobilizing billions of dollars in financing to support countries as they weather the crisis. These institutions are uniquely positioned to incentivize inclusivity by governments in their pandemic response plans.

Third, the very concept of refuge is under assault. In response to the pandemic, it is estimated that 164 countries across the globe have limited or cut off access to asylum. In some cases, governments have clearly weaponized public health concerns to advance nativist political agendas. The United States is a case in point. These countries must be urged to provide refuge for those with well-founded fears of persecution, even as they take reasonable steps to manage risks to public health. Such measures should also extend to policies around alternatives to detention of asylum seekers and other migrants. And countries in the midst of an outbreak should place a general moratorium on deportations of these populations.

Fourth, the measures taken to slow the spread of the COVID-19 are having unintended consequences in crisis zones. Border and market closures, lockdowns, and other movement restrictions are leading to bottlenecks in the humanitarian supply chain, massive spikes in food insecurity, and a loss of livelihoods. The UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Mark Lowcock has warned that ten countries could fall into famine over the next six to nine months. According to the UN Secretary-General António Guterres, the pandemic has been accompanied by a “horrifying global surge” in gender-based violence. In some crises, the impact of these disruptions on the displaced and other vulnerable populations may be more severe than the impact of the virus itself. Governments, donors, and aid agencies need to take swift action to mitigate these unintended consequences.

Finally, the global humanitarian response to the crisis continues to suffer from an absence of leadership from major world powers, even as it remains woefully underfunded. The UN and other multilateral agencies are struggling mightily to meet needs. However, these efforts have been undercut by squabbling between the United States and China and the former’s attacks on the World Health Organization. For their part, donors need to step up across the board, but this must be done without diverting aid from other relief efforts. Finally, not enough has been done to fund and empower local aid groups on the frontlines of the crisis.

Juggling all this will not be easy, and some of these priorities may be in tension with one another in different regions of the world. However, striking the right balance is essential to safeguarding the world’s most vulnerable individuals from the full weight of the pandemic.

Regional Snapshots

Latin America—home to 8.3 million IDPs and 300,000 refugees and over 4.2 million displaced Venezuelans—is now the epicenter of the pandemic. The region accounts for nearly half of the world’s COVID-19 cases and deaths. The World Health Organization (WHO) is deeply concerned that the virus could overwhelm the capacity of the public health system in many countries there. In addition, the World Food Program (WFP) reports an almost three-fold rise in the number of people requiring food assistance as a result of the pandemic. As governments struggle to respond, refugees and forced migrants are suffering disproportionally.

The situation is particularly acute for the millions of Venezuelans who have fled their country. Many displaced Venezuelans lost their livelihoods as host countries imposed lockdowns to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Those working in the informal economy have been particularly hard hit. Without income to pay for rent and basic needs, they have been evicted, left to face rising food insecurity and poverty with no place to live. UN officials warn that the pandemic will place up to 1.5 million Venezuelans at risk of extreme hardship, particularly as winter sets in and temperatures drop in South America. The deteriorating economy has also provoked xenophobic sentiment in many host countries. As a result of all these hardships, tens of thousands are now making the previously unthinkable choice to return home to Venezuela.

In the Middle East, the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 remains relatively low, at around 630,000. Of the almost 14 million forcibly displaced people in the region, only a fraction has been diagnosed with the virus. However, it is likely that these numbers significantly undercount the true scale given the limited testing available. Moreover, the Middle East remains one of the most crisis-stricken parts of the world. Protracted conflicts have driven large waves of displacement amid the destruction of property and critical infrastructure, leaving many individuals vulnerable in the face of a pandemic.

Refugees and IDPs in the region are among those at highest risk. This is particularly true in camp-like settings in places like Idlib province in Syria, where millions of IDPs live in population-dense areas with limited services and inadequate sanitation. Indeed, reports in the last few days of the first confirmed COVID-19 cases in Idlib have set off alarm bells. In Iraq and Gaza, the economic shockwaves of the pandemic are exacerbating food insecurity and malnutrition among displaced communities.

The situation in Yemen is currently of the most significant concern. The official number of approximately 1,350 confirmed cases is likely a massive undercount, understating the magnitude of the crisis. Health centers and graveyards are at or over capacity. With little or no personal protective gear and few medical supplies, some doctors are reportedly abandoning their hospitals out of fear of contracting the virus. The country’s fragile healthcare system is at the point of collapse. The head of the UN in Yemen, Lise Grande, warns that the death toll in Yemen from the pandemic could “exceed the combined toll of war, disease, and hunger over the last five years.”

In West and Central Africa, the coronavirus continues to spread steadily. There are 100,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the region. However, the pace of transmission is accelerating. While infection rates among the forcibly displaced population remain relatively low, the pandemic is already affecting the region’s nearly 6 million IDPs. There are more than 2.8 million IDPs in the Lake Chad Basin; more than 1.1 million IDPs in the Central Sahel; and nearly 2 million IDPs in Cameroon, Nigeria, and in the Central African Republic. Escalating violence has forced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes over the last year alone.

Most displaced persons live in close quarters with host communities or in congested camps or camp-like settings that leave them highly vulnerable to infection. Meanwhile, pandemic-related restrictions on movement and the economy are exacerbating food insecurity and interrupting the flow of humanitarian assistance. Prior to the outbreak, countries in the region were already in the grip of an unprecedented food security crisis. An estimated 12 million people faced food shortages in 2019, a figure that could reach 20 million by August 2020.

In the East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes region, about 40,000 COVID-19 cases have been confirmed among countries hosting displaced persons. The region is home to about 4.6 million refugees and 8.1 million IDPs. However, as in West and Central Africa, the pandemic is exacerbating food shortages in a region where 27 million people are already at the crisis stage of food insecurity.

In South Sudan, new rounds of violence threaten the stability of the country’s fragile peace process. COVID-19 infections have been reported in the Protection of Civilian sites on UN peacekeeping bases, which host more than 190,000 IDPs. Senior aid officials warn that the disease is spreading quickly and threatening the integrity of the country’s weak public health system.[1] Meanwhile, pandemic-related restrictions are limiting humanitarian access to displaced communities. Aid agencies report having to reduce their staff presence and services after personnel become infected themselves.

In Asia, the Rohingya remain one of the main displaced populations of concern. Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh host the world’s most populous grouping of refugee camps, with more than 860,000 Rohingya refugees. Camp conditions facilitate the rapid transmission of the virus—high population density makes physically distancing impossible, and adequate healthcare services and infrastructure are absent. Although there are relatively few cases confirmed among refugees, humanitarian workers fear that camp residents may be foregoing testing to avoid the mandatory isolation involved.

All the while, Rohingya continue to flee Myanmar, many leaving by boat. Citing concerns about the coronavirus’ spread, governments in the region are refusing to let rescue ships dock. At least three boats of Rohingya refugees were refused entry in Bangladesh and Malaysia, leaving hundreds stranded in the open ocean for weeks.

In Europe, experts said the first wave of coronavirus transmission had “passed its peak” in late April 2020. At the end of June, there were more than 2.67 million cases of coronavirus in Europe. Although concerns about large-scale outbreaks in refugee camps in Greece have not materialized thus far, the health crisis has directly impacted the more than 3 million refugees and asylum seekers in the European Union (EU). Several governments took some positive measures to protect asylum seekers and refugees. However, the closures of borders and immigration bureaucracies effectively eliminated access to asylum. Moreover, shuttered economies and overwhelmed health systems have left asylum seekers already in Europe without income, shelter, or other basic needs.

After reaching its highest level in two years in early 2020, the number of asylum applications in the EU+ region[2] dropped 43 percent in March—the lowest level since early 2014. However, EU countries ultimately expect an increase in asylum applications as a result of the pandemic’s impact on refugee-sending countries. EU Member States have so far been unable to agree on much-needed reforms to the regional asylum policy. A failure to do so will undermine Europe’s ability to adequately prepare for a new wave of global displacement.

Humanitarian Priorities

The pandemic’s distinct impact on forcibly displaced communities across different regions of the world means there is no single solution to address its harms. Instead, governments and aid agencies must seek to vindicate competing priorities. Success will require key stakeholders to be flexible and creative and to coordinate across geography and function. Five key priorities should guide this effort.

Contain and Mitigate the Pandemic in Crisis Zones and Displaced Communities

Camps and camp-like settings

The Director-General of the UN’s migration agency, Antonio Vitorino, recently warned that camps remain his “worst nightmare.” The virus has been detected in dozens of refugee camps across the globe, where testing and treatment are inadequate. Senior UN humanitarian officials estimate that the virus’s peak is still “three to six months” away in many humanitarian crisis zones. Humanitarian groups warn of the heavy toll an outbreak is likely to take in these settings, where physical distancing is impossible, access to hygiene and healthcare is minimal, and many individuals struggle to secure basic rights and services.

In camps or host communities, displaced people need reliable and up-to-date information to protect themselves from the coronavirus. However, host governments’ failure to improve communication with displaced communities has left gaps or resulted in the spread of misinformation about the disease. In extreme cases like Myanmar and Bangladesh, authorities block cellphones and internet service in refugee and IDP camps. Governments must not only roll back any restrictions on access to information but also work with local community leaders and humanitarian workers to build trust and improve information sharing with displaced communities.

Medical supplies

At a global level, the UN estimates that coronavirus responses will require at least 100 million masks and gloves, 25 million respirators, and 2.5 million diagnostic tests every month for the foreseeable future. The shortages of PPE and testing that have plagued the United States and Europe are proving far worse in humanitarian crisis zones. These shortages threaten to collapse fragile public healthcare systems, thereby magnifying the pandemic’s humanitarian toll even beyond the immediate crisis. Donors and aid agencies can even be part of the problem. For example, until recently, USAID placed restrictions on the use of its funds to procure and ship PPE around the world.

Solving the medical supply shortfall has fallen largely to the United Nations COVID-19 Supply Chain Taskforce. The inter-agency taskforce’s mandate is to massively scale up the procurement and delivery of personal protective equipment, testing and diagnostics supplies, and medical equipment like ventilators. In June, the UN reported that the taskforce had shipped more than 250 million PPE items to countries around the world. While this effort has been impressive effort, senior humanitarian aid officials in several regions continue to report widespread shortages, including in camps and other displaced communities. In addition, it is not clear that the taskforce facilitates other essential resources, such as basic hygiene supplies, and materials to build isolation units and shelters needed to decongest camps. These remain in short supply.

Vaccine nationalism

The same market dynamics that make it hard to get PPE are putting also key treatments out of reach. Remdesivir, the first approved antiviral treatment, has been priced at about USD 3,200.00 per clinical course. This is clearly far too expensive for much of the world’s population. Even countries like Mexico, which participated in the trials to assess efficacy, cannot acquire the drug. Indeed, the United States has already purchased much of the world’s supply. Another treatment, Dexamethasone, is already generic and widely available. However, there is no plan for getting that drug into humanitarian crisis zones or refugee camps.

These experiences preview the challenges that host countries and aid agencies alike will face when a coronavirus vaccine is finally available. In April, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling for “equitable, efficient and timely” access to any vaccine developed to fight the pandemic. The WHO has set up an initiative with member states and private foundations to produce and distribute both therapeutics and a “people’s vaccine”. The initiative has set ambitious goals, including the production of 500 million tests, 245 million treatment courses and 2 billion vaccine doses.

However, the WHO effort remains massively underfunded. Countries like China and the United States have yet to contribute. Meanwhile, governments with deep pockets are making deals with major pharmaceutical companies to mass produce vaccines for domestic consumption. All this suggests some of the world’s most needy will be left out. So far, those insisting on equity of access to a vaccine have focused primarily on distribution across countries. However, for a future vaccine plan to be truly effective, it will also need to prioritize equitable access for vulnerable populations and to accommodate distribution in humanitarian crisis zones. This will be no mean feat in the face of the vaccine nationalism.

Include the Forcibly Displaced in the Response and Recovery

An effective response to the pandemic must be inclusive. International assistance efforts must not only reach—but also engage—all vulnerable populations, including refugees, asylum seekers, and IDPs. Ensuring that these individuals can access public services and social welfare programs in their host countries is critical. This is particularly true for urban refugees and others who live outside formal camps where aid agencies provide support.

Relevant social protection schemes include access to healthcare, shelter, and cash transfers to substitute for wage loss. International financial institutions such as the World Bank can leverage financing to fund these schemes and incentivize governments to include displaced populations. Their role is particularly important in light of the massive global economic downturn to result from the pandemic.

Already, the Bank is mobilizing $160 billion over the course of 15 months to help countries respond to the immediate health consequences of the pandemic and bolster economic recovery. The first wave of grants and concessional loans were designed to fund everything from disease surveillance systems to PPE to vaccine research. In addition, the Bank is working to shore up social safety nets, preserve jobs, and shorten the overall recovery time for deeply affected economies.

As of July 2020, the Bank had approved over 130 loans and grants in over 100 developing countries as part of its COVID-19 response. Recipients include governments in almost every country where the UN is currently responding to a displacement or other humanitarian crisis. A quick review of the available project documents reveals that some explicitly include or target forcibly displaced populations. However, the majority of projects in for host countries do not make direct reference to the inclusion of refugees or the IDPs.

Certainly, the displaced will benefit from an overall injection of financing in their host communities. However, as others have argued, the Bank and the other IFIs should make an effort to explicitly include them in their pandemic response strategies to ensure they receive the targeted support they need. The Bank should also ensure that national COVID-19 response plans and social protection schemes meet the needs of displaced populations, especially in urban areas. These interventions should also prioritize commonly excluded and highly vulnerable groups within displaced communities such as women, the elderly, and people living with disabilities.

Better cooperation between the UN system and IFIs can also strengthen inclusive responses. The UN’s global response plan has three main components: 1) strategic preparedness to address health needs; 2) the Global Humanitarian Response Plan; and 3) a blueprint to help socio-economic recovery. It has estimated needing more than $10 billion to fully fund these efforts.

These UN workstreams clearly overlap with those of the World Bank. Both institutions are coordinating these interventions at the country level. This makes sense in the immediate as the in-country teams have the best understanding of the pandemic’s local dynamics and the needs on the ground. However, over time, greater coordination at the strategic level may improve both efficiency and effectiveness across the board. It would also provide an opportunity to establish a joint commitment and plan to reinforce refugees and IDPs’ inclusion in the global response.

Restore the Right to Asylum and Strengthen Protection for the Displaced

Asylum and rescue

In recent years, refugees and asylum seekers have faced a profoundly concerning trend: the progressive erosion of asylum space. Even Europe and the United States—traditional pillars of the international humanitarian system—have curtailed their welcome to those seeking protection. Governments have built physical and invisible walls to keep refugees and asylum seekers away. From refoulement to resettling fewer refugees, these policies often reflect the rise of populist politics that demonize outsiders.

The pandemic has accelerated this trend. Nativist leaders have weaponized public health concerns to justify unnecessarily harsh measures in service of anti-immigrant and anti-refugee agendas. In early June, UNHCR reported that of more than 160 countries that had imposed border restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19, at least 99 were making no exception for people seeking asylum. This, despite its guidance that “denial of access to territory without safeguards to protect against refoulement cannot be justified on the grounds of any health risk.” These measures have had a significant impact on the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. Individuals have been unable to cross international borders to seek protection, family reunification procedures have been interrupted, and asylum seekers have been abandoned at sea as countries refuse to allow rescue ships to dock. Governments must provide refuge to those with well-founded fears of persecution, even as they take reasonable steps to manage potential risks to public health. In some cases, the need for change is extremely urgent.

Detention and deportation

Advocates have long called on governments to end harmful practices of detaining and deporting asylum seekers. In the midst of a public health crisis, these calls only become more urgent. The deplorable conditions individuals face in detention and the process of deportation expose them to infection and may contribute to the virus’ spread. Such forced returns intensify public health risks for the displaced, health workers, and both host and origin communities.

Some European countries have already imposed a de facto moratorium on deportations. Others have released asylum seekers and other migrants from detention facilities. However, the United States continues both to detain and deport. To date, approximately 3,000 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainees have tested positive for COVID-19, and the number continues to climb. ICE also continues to deport asylum seekers and other migrants to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. In at least 11 countries, deportees have tested positive for the virus upon arrival in their home countries.

Xenophobia and stigma

Domestic crisis situations—and disease outbreaks and economic disasters, in particular—can trigger nationalist and xenophobic attitudes among publics. UN agencies and humanitarian groups already report growing stigma, discrimination, xenophobia, and hate speech directed at refugees and other migrants around the world. Tensions between displaced persons and their host communities are likely to continue rising with the human and financial toll of COVID-19. These trends stand to further marginalize already-vulnerable people and encourage populist leaders to introduce hostile policies. UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called on governments and peoples to “act now to strengthen the immunity of our societies against the virus of hate.” Donors, host governments and aid organizations should prioritize efforts to improve social cohesion through their programmatic work. This will make both displaced people and their host communities safer.

The “silent pandemic”

Women and girls face unique challenges during over the course of the pandemic. Shelter in place policies and self-quarantines have slowed the spread of the disease. However, they have also led to an alarming spike in gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV). The UN Secretary-General has acknowledged the “horrifying global surge in domestic violence” resulting from the lockdowns – what has become known as the “silent pandemic.”

For displaced women and girls, the effect is to exacerbate the risk level of a population already highly vulnerable to gender-based violence. In camp and shelter settings, there are few truly “safe spaces” for women and girls. Those that did exist are now closing. Aid workers in refugee camps from Bangladesh to the Greek islands are already seeing higher rates of IPV than usual. Women’s healthcare is also suffering. In some settings, sexual and reproductive health services are being interrupted or eliminated altogether.

Manage the Humanitarian Consequences of the Pandemic Response

Humanitarian operations

Among the unintended consequences of governments’ efforts to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, one of the most significant has been the disruption of the international humanitarian supply chain. More than 90 percent of the world’s populations lives in countries that have enacted national travel restrictions and border closures at one point during the pandemic. Some have restricted exports of essential equipment and medicines, and cancellations of air freight and maritime transport have created bottlenecks. Borders closures have delayed emergency activities by blocking entry of personnel and supplies, including for critical water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); nutrition; and shelter interventions. They have also prevented humanitarian staff rotations and expert deployments to fill knowledge or skill gaps.

All this has made it harder to continue delivering relief in protracted humanitarian crisis zones like South Sudan. The disruptions have also slowed efforts to scale up humanitarian relief in response to new disasters like the recent tropical cyclones in the Pacific and South Asia and the desert locust crisis in East Africa. Refugees and IDPs affected by these crises—most of whom depend on humanitarian aid—have been deeply impacted.

Food security

More than half of the world’s refugees and IDPs live in countries and communities that faced high levels of food insecurity even before the pandemic. Now, lockdowns and border closures have further reduced food availability. These measures have closed markets, prevented farmers from accessing their lands, and disrupted supply chains. As a result, WFP estimates that the number of people facing acute food shortages will increase from 149 million to 270 million by the end of 2020. In East Africa, at least 60 percent of refugees are already experiencing food ration cuts. In the Middle East and the Sahel, the food security threat posed to IDPs could be equal to or greater than the pandemic. To address the crisis, WFP is undertaking the “biggest humanitarian response in its history.” It will mobilize resources to assist up to 138 million from a record 97 million in 2019. However, even if the agency is successful, about 130 million people will remain on the edge of famine by year’s end. Governments can and therefore should lessen the impact of border restrictions on food security. For example, under the guidance of WHO, some countries in the South Pacific hit by Tropical Cyclone Harold tailored their disease mitigation measures to facilitate and accelerate delivery of life-saving international aid. In addition, WFP is engaging authorities in many countries to find ways to open markets and untangle food supply chains amid the pandemic. African Union (AU) governments have jointly agreed on measures to do the same at a regional level. Other countries have opened humanitarian corridors to fast track the delivery of food and other forms of aid.

Aid agencies and public health experts can help governments put these arrangements into place, particularly in crisis zones. WFP is particularly pivotal not only because of its role in supplying emergency food aid but also because it serves as the logistical backbone of the UN’s global humanitarian response to the pandemic. To this end, the organization has established international and regional staging areas and leased aircraft from commercial carriers to facilitate the flow of relief. This endeavor is both ambitious and costly. By the end of June, WFP had raised only $178 million of the $965 million it will need to maintain this operation through the end of the year.

Jobs and livelihoods

Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the resulting global economic slowdown have cost many people their jobs and livelihoods. The World Bank estimates that COVID-19 could push-up to 60 million people into extreme poverty in 2020 alone. The millions of refugees living in low- and middle-income countries have been disproportionately affected. These refugees are sixty percent more likely than host populations to be working in some of the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic, such as manufacturing, retail, and the informal sector. Before COVID-19, initiatives to lower barriers to the labor market were underway in many refugee-hosting countries. Governments and the private sector should push these initiatives forward while putting in place adequate testing and other measures to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19.

Resource and Lead the Global Response

The funding gap

Making real progress in all of these areas depends upon two things: resources and leadership. Unfortunately, the international response has fallen short on both fronts. The current UN Global Humanitarian Response Appeal calls for $6.7 billion to fund efforts to contain and mitigate the pandemic. That number is expected to approach $10 billion when the UN releases a revised version of the appeal later this week. As of July 9, donors have only pledged $1.64 billion. While more money is desperately needed, funding should not be diverted from existing humanitarian programs despite budgetary pressures most donor countries face.

The United States, particularly the U.S. Congress, has an important role to play in mobilizing emergency funding. Although Congress approved several emergency COVID-related funding supplementals in March 2020 that included international assistance, it can do much more to prioritize international assistance. Specifically, it should approve at least an additional $12 billion for the global pandemic response which would provide support for needed global health services, flexible humanitarian assistance, and frontline workers in the international fight against COVID. Furthermore, U.S. funding already approved for the COVID-19 international response, including emergency funding passed by Congress in March 2020, must get to the operational organizations in the field as soon as possible.

In addition, donors and aid agencies must do a better job of resourcing local groups and capacity. The international humanitarian community has long aspired to empower and channel more funding through its local counterparts. To date, efforts have fallen short. The pandemic has given the localization agenda a renewed urgency, particularly as international aid workers have been pulled back from or lost access to displaced populations in coronavirus hot spots.

However, recent research demonstrates that countries have primarily channeled funding for the COVID-19 response through large UN agencies. In many cases, this funding has yet to reach local partners on the front lines of the response. Without renewed pressure to accelerate the flow of resources to local partners, the spread of the virus will continue to outstrip efforts to contain and mitigate the pandemic in the most vulnerable communities.

The absence of great power leadership

Last, but certainly not least, is the vexing absence of leadership for the global pandemic response. The international coordination challenge for the aid sector is almost without precedent. Yet no significant grouping of global leaders has come together in a sustained fashion to jump-start truly global cooperation in response to the pandemic. Indeed, it is hard to imagine a crisis—even one half its dimension—where the international community had done so little to rally together.

The approach of the United States is particularly striking. Rather than lead, the Trump administration walked away from the WHO and squabbled with key member states like China. Until recently, the UN Security Council has been paralyzed by the infighting between its permanent members. It took months for the world body to pass a resolution calling for global “immediate cessation of hostilities” in warzones around the globe to facilitate the response to the virus – something the UN Secretary-General had called in March. Sorely missing has been the kind of leadership that was on display during the West Africa Ebola crises in 2015 or even the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004.

Much ink has been spilled on how the pandemic will remake the international order. But those working to manage the current crisis must make do with the tools at their disposal. In the absence of great power leadership, some regional groupings are picking up the slack. For example, EU Member States agreed for the first time to float an EU bond to raise money to fund its members’ recovery. European leaders also convened a global donor conference in May that secured over $8.3 billion in pledges to fund research and development for vaccines and treatments. In Africa, African Union Member States have largely coordinated their own response to the pandemic through the Africa Centres for Disease Control. But even if regional multilateralism proves effective, a global pandemic still requires a truly global response.

Recommendations

Surge the health response in crisis zones: Donors and aid agencies should redouble their efforts to bolster the health response in humanitarian and displacement crises. The provision of essential medical supplies like personal protective and diagnostic equipment remains critical. The UN taskforce set up to coordinate this effort will need additional funding, diplomatic support, and private sector engagement to do so effectively. Aid agencies will need to improve their strategic flexibility to pivot the flow of essential supplies from one hot spot to another as new ones emerge. The UN should also consider broadening the mandate of the taskforce to include hygiene, sanitation, and other materials to help refugees and IDPs protect themselves against the virus.

Ensure access to a future vaccine for the most vulnerable: Donors should ramp up support for the WHO-led initiative to develop and distribute a “people’s vaccine.” A fundamental goal of this effort is to provide countries equitable access to a vaccine. However, the blueprint to develop and distribute the vaccine should also give priority to ensuring equitable access for the world’s most vulnerable populations. It must also include plans for delivery in humanitarian and displacement crises zones. Host governments must also commit to including displaced populations in their national vaccine distribution plans.

Unblock food and humanitarian supply chains: The number of people expected to become acutely food insecure is expected to double by the end of the year. Donors and aid agencies should partner with governments in crisis zones to collect and share best practices on how to minimize the impact of pandemic restrictions on food supply chains and the provision of relief aid. Such measures could include humanitarian corridors, special visas for essential humanitarian staff, and fast-track procedures for aid delivery. In addition, donors must urgently fill the over $780 million shortfall in funds required by WFP to maintain the logistical backbone of the UN’s global humanitarian response through the end of 2020.

Include the forcibly displaced in national pandemic responses and social welfare systems: International financial institutions, bilateral donors, and aid agencies should ensure that loans, grants, and other forms of COVID-19 assistance incentivize host governments to include forcibly displaced populations in their social welfare and protection schemes. This is particularly important for refugees and internally displaced who are not living in formal camps and lack direct access to aid agencies. Economic support packages should also incentivize host countries to continue to lower barriers to refugee participation in the labor market.

Ensure targeted aid for women and girls: The pandemic has dramatically and uniquely impacted displaced women and girls. Aid agencies must prioritize the use of gender analysis to inform their COVID-19 programming. Donors and aid agencies should increase the percentage of overall funding dedicated to combatting gender-based violence (GBV). They should also treat women’s healthcare as essential programming and ensure that budget lines earmarked for women’s health and GBV are included in all COVID-19 related appeals and programming.

Restore asylum and protect the rights of those fleeing violence and persecution: Governments must rescind restrictions on access to asylum and rescue at sea imposed in the name of public health. Governments should rely on alternatives to detention for asylum seekers other migrants and provide these individuals access to testing and healthcare. In the current situation, in which governments (like the United States) risk exporting COVID-19 to destinations with fragile public healthcare systems, governments should place a general moratorium on deportations of asylum seekers and other migrants. Moreover, under no circumstances should such individuals be returned without being tested for COVID-19.

Increase funding and accelerate the flow of resources to the front line: Donors need to step up across the board to fully fund the almost $10 billion revised UN Global appeal, scheduled for release on July 16th, for COVID-19 humanitarian response. For its part, the U.S Congress should approve at least an additional $12 billion for the global pandemic response, including support for global health services and flexible humanitarian assistance for the international fight against COVID. In addition, the United States and other major donors need to accelerate disbursement of assistance to relief agencies, in general, and to increase the flow of resources, in particular, to local aid providers who are on the frontlines of this crisis. Donors should also prioritize national-level pooled funds to which local humanitarians have access.

Improve coordination and integration between the UN and the World Bank: The UN Secretary-General and the President of the World Bank should consider establishing a high-level joint taskforce for the pandemic to help coordinate and drive the response across the main pillars of the Bretton Woods system. The taskforce could build upon existing World Bank-UNHCR coordination with respect to the Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) funding mechanism for refugees. The taskforce would ensure greater unity of effort across the health, humanitarian, and recovery elements of the response. It would help ensure that the world’s most vulnerable populations, including the forcibly displaced, receive both the priority and inclusion that they need and deserve.

Convene a leaders’ summit at the 75th UN General Assembly: The UN Secretary-General and world leaders should convene a leaders’ summit on the pandemic on the margins of this year’s 75th anniversary of the UN General Assembly. The summit could be modeled broadly on similar initiatives in the past to address critical issues that have both humanitarian and international peace and security implications, such as peacekeeping efforts and the global refugee crisis. Summit participants would make commitments to support various aspects of the pandemic response based on their own national capacities and expertise. Governments involved in the effort to convene this UN summit could subsequently ensure that COVID-19 is on the agenda for the G-7 and the G-20 later this year.

Endnotes

[1] Interview with the author.

[2] The EU+ includes the 27 EU Member States, United Kingdom, Norway, and Switzerland

Cover Photo: A woman holds her baby at a makeshift camp where Venezuelan migrants are living during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bogota. (Photo by DANIEL MUNOZ / AFP) (Photo by DANIEL MUNOZ/AFP via Getty Images)