The Humanitarian Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Venezuelans in Peru, One Year In

Introduction

More than 5 million Venezuelans have made the difficult decision to leave their homes due to the grave humanitarian crisis in Venezuela. Many of the over 1 million Venezuelans in Peru made extremely challenging journeys and faced barriers to entry to find refuge in a new country. Most had high aspirations for their new life in Peru. Yet, for many, these aspirations have been dashed due to the pandemic and lockdown measures. Peru first entered lockdown for the COVID-19 pandemic on March 15, 2020, and despite strict public health measures implemented over the last year to contain the virus, the pandemic rages on. This report documents the experience of Venezuelans living in Peru one year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the Peruvian federal and local governments have made some good advancements in access to education and temporary work opportunities such as improving access to education and providing support to victims of gender-based violence, humanitarian support during COVID is lacking. The Peruvian government provides little humanitarian assistance to Venezuelan communities, preferring to leave this responsibility to international organizations, most notably the United Nations system. There have been some noteworthy successes in new options for regularization in the country and promising support from local governments. Despite some successes, the Peruvian government recently decided to militarize the northern border of Peru to control migration, which may force Venezuelans on the move to enter irregularly, pushing them into precarity.

To better support Venezuelans during this challenging time, the Peruvian government should take bolder steps to incorporate Venezuelans into its broader government strategy for COVID-19 relief. The government should also consider regularization options such as an expansion of the scope of an already existing humanitarian residency option for Venezuelans inside Peru. Civil society organizations should expand their outreach and work alongside Venezuelan-led organizations but need greater support from the international community. Finally, both the Peruvian government and international donors should ensure vaccinations for Peruvians and Venezuelans alike as this is essential for COVID recovery.

This report draws on the testimonies of Venezuelans living in Lima, where approximately 85 percent of Venezuelans live. Pseudonyms were used to protect the identity of those who were interviewed.

Difficult Journeys to Peru

Venezuela Context

Venezuela is facing one of the most serious economic and social crises in the world. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, between 2018 and 2019 the crisis worsened in Venezuela as the economy continued to contract, inflation skyrocketed, and public revenues fell because of a drastic reduction in oil exports. Venezuelans suffer violations of their economic, social, civil, political, and cultural rights daily.

Food Insecurity

Food security is often the catalyst for the displacement of many families. No matter how hard they try to adjust their budget, it is not enough to guarantee quality, nutritious food. Often, adults limit the quality and quantity of their daily rations, and even stop eating for the sole purpose of providing children with food. According to National Survey of Living Conditions (ECOVI for its Spanish name), food insecurity affects all households in Venezuela, regardless of income. According to their research, 56 percent of households report that they have run out of food in the last month due to lack of money or resources. The lack of food also contributes to high rates of chronic malnutrition among children. A Venezuelan in Peru describes the situation in an interview with Refugees International and Encuentros SJM:

My motive for leaving is that I have two children, and I needed to find food for them. The government gives one basket of food monthly, but it is only rice and pasta, and it was not enough to sustain us. It was very difficult to eat a piece of chicken or even an egg. It was very difficult to get food for the children. When I became pregnant…I left the country out of fear that things would become more difficult. Even though my partner had a job, it was not enough.

—Gabriela, a Venezuelan in Peru

Health

Venezuela’s health system is also in severe decline. Public hospitals lack basic supplies, infrastructure is in disrepair, and medical personnel are scarce as many have left the country. The president of the Pharmaceutical Federation of Venezuela stated the scarcity of medicines is at critical levels, with an 80 percent shortage of available medication. The lack of medication for various illnesses and conditions is major challenge in the day-to-day life of Venezuelan people.

There were days where we only ate once, or we did not eat at all, or we had to walk a great deal because we live in a rural town. My son always had health problems, and the Central Hospital was very far away. There wasn’t any transport, so we had to walk to the hospital.

—Maria, a Venezuelan in Peru

Work Opportunities

Finally, lack of formal work opportunities is another main push factor for Venezuelan displacement. Venezuelans face massive layoffs, very low wage jobs, and difficulties in accessing work due to shortages of gasoline and paralysis of public transport. Vehicle repair companies have ceased to operate in the country and often the only alternative is to travel on foot or risk the use of improvised means of transport. This situation has forced people who were carrying out formal activities to seek informality as a buffer to cope with the economic crisis.

In Venezuela I had a job, but it was not enough. My mother-in-law decided to leave Venezuela because the situation is so hard. Even though we tried to sell sweets, the money did not stretch far enough. We had to choose between eating or medicine. We did not have money for both, not even enough to eat well for a week. We had to choose one.

—Carlos, a Venezuelan in Peru

Uncertainty and Risks During the Trip

For many Venezuelans, leaving Venezuela becomes the only hope for them and their families. The majority of Venezuelans move to countries within Latin America and the Caribbean, with most people going to Colombia and Peru. According to information from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, more than 1 million Venezuelans have arrived in Peru, and more than 496,000 have requested refugee status. This makes Peru the host country with the highest number of Venezuelans seeking asylum and the second destination for Venezuelan refugees and migrants worldwide. The figures reflect the magnitude of the migratory flow of Venezuelan individuals and families to Peruvian territory.

The Journey

After leaving Venezuela, Venezuelans travel south through Colombia and Ecuador to Peru. Throughout this journey, Venezuelans are in vulnerable conditions, often leaving their country with little or no resources. They embark on a trip that can last for a few days and up to months as most Venezuelans travel by land—some traveling sections of the journey by bus, and other sections on foot. Moreover, displaced Venezuelans are often forced to take irregular routes to reach safety, typically because of fear of being denied entry to Peru.

We ended up walking at night, and we saw many lanterns. It was the Colombian guerillas, as they know what the situation is. They wait there to rape women or take them to work as servants, and sometimes kidnap children.

—Juan, a Venezuelan in Peru

The lack of shelter is another problem. The cold presents a risk of illnesses, especially when Venezuelans spend hours or days sleeping on the street because they do not have the resources to find a place to stay. They are also exposed to insecurity and street crime. Hunger is another concern, especially for children. Some Venezuelans only have something to eat thanks to the solidarity of passers-by who see the precarious conditions of those who travel and offer help. Children face hardships that are difficult for even adults to endure. Long walks, traveling by bus for hours, standing, waiting for food, and fatigue are just some of the situations that children face along the journey.

In the situation of being on the road, one goes through many things. The hunger. The cold. My son got pneumonia because we had to sleep on the street in a plaza.

—Maria, a Venezuelan in Peru

Walking to Pamplona, my son couldn’t walk. He cried because he got so tired…

—Carlos, a Venezuelan in Peru

Arrival at the Border

The challenges of the journey ideally would end upon arrival to the Tumbes at Peru’s northern border with Ecuador, where the majority of Venezuelans enter the country. But interviewees report facing protection risks upon arrival, such as the long lines at the bi-national checkpoint on the Ecuadorian side to enter Peru, having to wait for days at the border, and sleeping in the open. In other cases, Venezuelans were pressed by the authorities to enter Peru quickly, and interviewees recall only getting a stamp on their documents and continuing their journey to Lima, without receiving any information about migratory regularization or the refugee system from the humanitarian actors at the border.

Others crossed through irregular routes because they did not have the proper documentation to enter regularly, meaning they were not given the opportunity to seek asylum. Even before the pandemic, it was quite difficult for Venezuelans to enter Peru due to strict requirements. Now that the borders are closed due to the pandemic, entry is nearly impossible, so many make the choice to enter irregularly. Entering irregularly makes them more susceptible to various risks such as being victims of trafficking, extortionists, criminals, and irregular armed groups. This is how some interviewees described the challenges:

We had to pay “under the table” because our youngest did not have a passport, just the two of us [Julia and her partner], and they wouldn’t let us cross….

—Julia, a Venezuelan in Peru

No, we didn’t [enter regularly], because we entered through a trocha [an informal entry], and when we entered Peru that week the pandemic had begun. They didn’t permit entry, and we couldn’t stay in Ecuador, and we didn’t want to return to Venezuela…

—Gabriela, a Venezuelan in Peru

However, others reported having received information about the shelter system and received vaccine support for the children.

Yes, they gave us information for my brother because my son and I had passports and he didn’t, so at the border they explained to him what we needed to do. They offered me information for my son because of his health situation. He was malnourished.

—Margarita, a Venezuelan in Peru

Pre-COVID Experience for Venezuelans in Peru

Before the pandemic, Venezuelans faced many challenges in Peru, but made important advancements thanks to regularization options and support from the Peruvian government and civil society organizations. Prior to 2018, Venezuelans could get what was known as the Permiso Temporal de Permanencia (PTP), a temporary work permit that allowed Venezuelans already in Peru to find formal labor opportunities, live without fear of refoulement, and granted access to basic services. However, in 2018, the government stopped issuing new PTPs, and in 2019, introduced visa requirements for Venezuelans attempting to enter Peru.

Although Peru holds the record for the highest number of asylum cases in the region, the rates of resolution—especially a positive resolution—are extremely low. Despite accepting the provisions of the Cartagena Declaration, Peru does not apply it to Venezuelan asylum seekers. There is a significant backlog in asylum claims, and stakeholders have described this as a “politics of waiting,” where Venezuelans are forced to wait sometimes years for a resolution. During this time, the documents they are given are sometimes difficult for employers, healthcare staff, and the education system to recognize and process.

Many Venezuelans had a hard time getting access to services, especially those with an irregular status. Prior to the pandemic, one out of two Venezuelan migrants in Peru had some illness—relapse of chronic illness, accident, or other mental health problem such as depression, fear, anger, anxiety, and stress—and had not visited a healthcare facility. In fact, half the Venezuelan population in Peru over 18 did not use Peruvian health services.

Prior to the pandemic, most Venezuelan children attended school, but there were many children and adolescents who did not. A Protection Monitoring assessment conducted in January and February 2020 revealed that 28 percent of children and adolescents did not attend school, largely because there were no open enrollment slots for the students or because of financial constraints. To get more Venezuelan children into school, the Regional Directorate of Education of Metropolitan Lima (DRELM) launched the campaign “Lima learns, not a child without studying” so that children and adolescents who did not enroll for the 2019 school year could still attend public schools in Lima. This strategy managed to adjust the school calendar so that classes took place from June 2019 to February 2020, making it easier for Venezuelan families to enroll their children.

The Pandemic

The Humanitarian Challenges of the Pandemic

At 1,158,337 cases and 41,538 deaths as of February 4, 2021, Peru has suffered tremendously during the pandemic. The secondary effects of the pandemic, such as the collapse of the economy and increase in humanitarian need, may be even more devastating for the country, especially for Venezuelan migrants and refugees.

The pandemic and the lockdown measures implemented by the Peruvian government massively affected the stability and integration of Venezuelans in Peru. The pandemic also thrust into stark relief the disadvantages Venezuelans face in the country, particularly those with an irregular status. Indeed, much of the recent progress described above rapidly deteriorated as Venezuelans began to struggle to provide for even their basic humanitarian needs. This was reflected in a needs assessment in December 2020 conducted by the Working Group for Refugees and Migrants (GTRM for its acronym in Spanish), a mechanism led by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

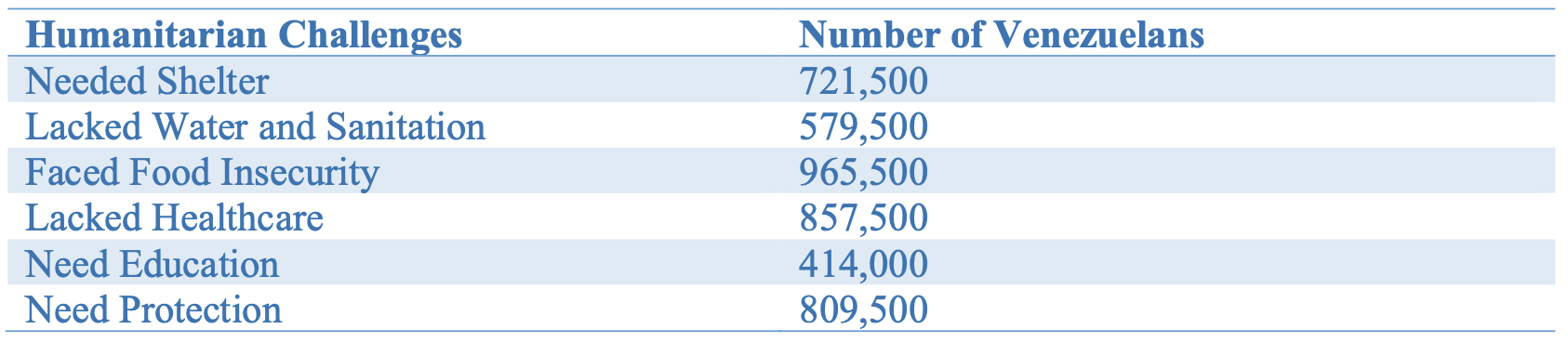

As of January 2021, roughly 721,500 Venezuelans and host community members needed shelter, 579,500 lacked proper water and sanitation services, 965,500 faced food insecurity, 857,500 needed healthcare, 414,000 need access to education, and 809,500 need protection. Many fled Venezuela because of inability to work, food security, and lack of healthcare. Now, Venezuelans face some of these challenges again in Peru.

Cases of COVID have remained high in Peru since the spring of 2020. Despite strict lockdown measures put in place by former president Martin Vizcarra, cases reached an all-time high in August 2020. Peru also had one of the highest death tolls in the region during this time. After a decline towards the end of 2020, cases began to rise again. On January 26, 2021, President Sagasti announced a total lockdown of the capital and nine other regions following a significant increase in COVID cases, which he said had pushed hospitals close to collapse. Although Peru has secured 48 million doses of the COVID-19 vaccine as of March 2, there is still a long road ahead. In the meantime, the Peruvian government will continue to adopt lockdown measures. Below are some of the major humanitarian effects of the pandemic and lockdown on Venezuelans.

Barriers to Health Services

Healthcare is fundamental to the well-being of Venezuelans in Peru, and especially so during the pandemic. Peru guarantees emergency health care to all Venezuelans, and those with a carnet de extranjeria, a type of residency card, can use the public healthcare option known as the Integrated Health System (or SIS for its Spanish acronym). SIS also provides free public healthcare to pregnant women and up to 42 days after giving birth, and children under five years of age can receive free public healthcare as long as the parents present an identity document.

However, both Venezuelans with regular and irregular statuses face difficulties in accessing healthcare. The GTRM estimates that less than 10 percent of refugees and migrants from Venezuela actually has access to SIS. Although SIS is universal for all Peruvians, Venezuelans have difficulty accessing SIS because the carnet de extranjeria is considered the only valid document for Venezuelans using the system. Venezuelans who have applied for asylum, for example, do not have access to this document. They receive another type of identification indicating they are asylum seekers. According to a study done by Encuentros SJM, 17 percent of Venezuelans have critical or chronic medical conditions. Peruvians and Venezuelans alike face barriers in their access to comprehensive healthcare under SIS, but Venezuelans are at a double disadvantage due to having an irregular status or, for those waiting for their asylum cases to be resolved, for their documents to be recognized. Others are simply burdened by the cost of health services.

These barriers have become even more pronounced and require urgent attention during COVID.

We were left with nothing. Without knowing what to do, we decided to go sell candy on the street, and that way we could buy food. When my wife gave birth, they [medical staff] did not want to treat her, and that situation hit me hard. I did not think it would cost 500 [soles] for a cesarean. And we did not have it. Others I know have difficulty getting their kids medical attention because of COVID.

—Juan, a 34-year-old asylum seeker in Peru

In general, COVID-related healthcare is hard to come by for Peruvians and Venezuelans alike due to the lack of healthcare infrastructure in Peru. Peru only has 1,656 ICU beds in the entire country, despite having a population of over 32 million people. Although cases have reduced since August, hospitalizations are higher, likely because people do not get tested early enough or wait too long to receive treatment. However, Venezuelans face particular barriers to getting COVID-related healthcare.

Venezuelans who work in the informal sector or who live in crowded living spaces may find it more difficult to safeguard against COVID-19. An Equilibrium CenDe June 2020 survey found that nearly half of Venezuelans surveyed share a room with three or more people, exhibiting a high rate of overcrowding. Yet, especially for Venezuelans with an irregular status, it can be difficult to get COVID tests. Some may be afraid to get tested out of fear of being returned to Venezuela. According to a study by the University of the Pacific’s Center for Investigation (CIUP), Venezuelan migrants reported that when they attempted to communicate with the health ministry to receive a COVID-19 test, they were denied because they did not have a National Identity Document, known as a DNI, or a residency document.

Secondary Effects of the Pandemic

The secondary effects of the pandemic—those effects that are not directly related to the virus, but rather the measures to contain the virus, such as lockdowns—have been even more far reaching than the virus. Many of the humanitarian challenges that Venezuelans face in the country are related to the loss of livelihoods due to lockdown measures. According to Refugees International and the Center for Global Development, 93.5 percent of working-age Venezuelans in Peru had jobs before the pandemic, but most of them were informal workers or self-employed (64.8 and 19.2 percent, respectively). Lockdown measures resulted in enormous job loss, especially for Venezuelans who work in the hardest-hit sectors.

Job losses have had significant humanitarian and protection-related impacts. In interviews conducted with Venezuelans in Peru, Refugees International and Encuentros SJM found that Venezuelans were resorting to selling goods on the streets for long hours in the morning and evenings to cope with the loss of employment. Many have struggled to pay for food or rent.

Three or four months I couldn’t go out and work, and the debt increased. I was desperate. The second month of quarantine, I started to sell on the street. I decided to do it so that I could buy food. After a month inside we had nothing, I had to go to the streets to bring in food.

—Carlos, a 25-year-old asylum seeker in Peru

Working on the street exposes Venezuelans not only to COVID, but also to other forms of risk, such as being victims of crime and exploitation. Venezuelan women face heightened protection concerns, especially when selling goods on the street during early morning or late evening hours where they are at risk of sexual and gender-based violence.

Food insecurity has also increased dramatically in Peru, and Venezuelans have had a particularly hard time providing for their basic daily meals during the pandemic. The World Food Program calculates that migrants and refugees in Latin America are exceptionally vulnerable because they are not included in national protection programs in times of crisis. This is the case in Peru. According to the Acción Contra el Hambre (Action Against Hunger) Peru, 78 percent of surveyed Venezuelans (2,000 families) reduced their food portions, and 58 percent decreased their number of daily meals in the pandemic. A staggering 92 percent of Venezuelans had to ask their friends and family for help with food to survive. Food insecurity worsened the longer the pandemic went on. In February and March of 2020, roughly 29 percent of surveyed Venezuelans had reduced their food intake to cope with insecurity, but by October and November, this number grew to 60 percent. Interviews conducted by Encuentros SJM and Refugees International reflect these statistics.

But there comes a moment where you feel pressured when dinner time comes, and you don’t have food, and you have kids. Well, the moment came where my brother and I, we would only eat once a day to be able to get through the quarantine.

—Ronald, a Venezuelan in Peru

Mental Health

After months of lockdown measures and general worry about contracting COVID, many Venezuelans are suffering from mental health challenges, including anxiety and depression. Another study by the CIUP found that half of women and roughly 40 percent of men surveyed during the pandemic had symptoms of anxiety disorder. Overall, one in three met the clinical definition for depression. These rates represent a decline in the mental health of Venezuelans. One year into the pandemic, mental health continues to be an issue of great concern.

[The pandemic hit me] very hard, because I feel it affected not just me, but the whole world. We have been so scared that something will happen to us, or to our kids. I have family that has died of COVID, and I feel that my hope has been taken away, my drive, my motivation to fight every day.

—Gabriela, a 25-year-old Venezuelan who arrived in Peru just a few months before the pandemic

I am scared to die here [in Peru]; I am alone with my son; I am afraid to die and leave my son alone. Currently I struggle to leave the house. I am not used to it, and I get scared of COVID.

—Maria, 34-year-old Venezuelan woman

Given the lack of healthcare services more generally, it is difficult for most Peruvians and Venezuelans to access mental health support through the public health system. Non-governmental organizations do offer some support to Venezuelans, but funding is limited as is the ability to provide in-person counseling due to health and safety measures. UNHCR and Encuentros SJM found that while nearly 90 percent of respondents suffered mental health concerns, only 12 percent have received some form of psychosocial support.1 These mental health concerns, coupled with humanitarian challenges, have been a push factor for Venezuelans to leave Peru to return to Venezuela, where they have a larger network of family but still very dismal prospects.

Housing

Paying rent continues to be a struggle for Venezuelans who have lost a steady income, and fear of eviction remains a concern. In Peru, 88 percent of Venezuelans live in a rental property, and only 0.2 percent own their home. Juan Guaido’s Ambassador to Peru, Carlos Scull, stated that over 55,000 Venezuelans were at risk of eviction in April 2020. A study by UNHCR and Encuentros SJM found that only 7 percent of Venezuelans surveyed did not pay rent in February and March 2020, but by November 2020, that number had risen to 45 percent.2 The GTRM Joint Needs assessment published in early 2021 estimates that 374,00 Venezuelan refugees and migrants need shelter in the country, which demonstrates that the need for affordable housing and policies to protect people from eviction remains a serious concern.

Rent is the most obvious [difficulty] after COVID hit—we had to go into quarantine, we could not leave, we couldn’t pay the rent, and this aspect hit me the hardest.

—Carlos, a Venezuelan in Peru

Populations with Additional Vulnerabilities

Children and Adolescents

Children of Venezuelan parents face specific challenges during the pandemic, particularly related to education services. Prior to the pandemic, approximately 21 percent of Venezuelan families in Lima were not able to enroll their children in schools or did not have the intention of doing so. During the pandemic, a June 2020 survey found that 31 percent of Venezuelans did not have their children enrolled in the education system and 40 percent were not participating in the Ministry of Education’s home learning program, due to lack of knowledge of its existence or because they did not have the proper technology to access the learning. UNHCR and Encuentros SJM found that 42 percent of Venezuelans surveyed had difficulty accessing internet.

The only thing I haven’t been able to get [in Peru] is a spot for my son to study. Every time I go to enroll him there is no space. If I went in December, they said I would need to come back in January. If I went in January, then said there wasn’t space, and so on…

—Juana, a Venezuelan in Peru

Children may also face additional pressure to provide economic support to the family during the pandemic, given the hardships many face due to job loss. Children who are participating in economic activities are often in precarious situations and denied their right to education. Rodolfo’s oldest son often helps provide income support to his family, working long hours during the day, while his younger son stays home alone:

I get up at 2:30 in the morning, and my 17-year-old son comes with [me] to sell on the street. We leave at 3:00 in the morning with a man who lives about 100 meters from where we live. He has a truck and a spot in the market. I go with him to buy vegetables to sell. We get back around 8:00 in the morning; my son stays home to get things in order, and my wife and I leave to sell on the street. I sell, and my younger son stays at home in the morning, sometimes alone and sometimes a neighbor checks in on him.

—Rodolfo, a Venezuelan in Peru

During the GTRM 2021 joint needs assessment, 58 percent of key informants identified children and adolescents as the most vulnerable populations in Venezuelan communities. Children and adolescents in an irregular situation are exposed to greater risks and different types of exploitation, including sexual violence. According to Peruvian government statistics, sexual violence against children and teenagers increased 852 percent from March to July.

Gender-Based Violence

Rates of gender-based violence (GBV) have skyrocketed since the onset of the pandemic, in Peru and across Latin America. For example, Peruvian government figures show that between March and August 2020 the number of reported cases of sexual violence against women increased 649 percent. It is difficult to obtain Peruvian government data on gender-based violence that is disaggregated by nationality, but a September 2022 study done by CARE found that 22 percent of surveyed female Venezuelans in Peru reported they had suffered from GBV. According to the Office of the Ombudsperson, an average of five complaints are filed daily concerning the disappearance of women, adolescents, and girls during the state of emergency. Women, especially trans women and LGBTIQ+ individuals face greater situations of discrimination such as harassment and xenophobia, especially in public places.

Returning to Venezuela: Between Yearning and Fear of the Uncertainty

As a result of the dramatic deterioration in conditions, many Venezuelans actively consider leaving Peru and returning to Venezuela. Interviewees stated that they considered going home because life had become too difficult in Peru, but most understood that life in Venezuela grows even more precarious day by day and that leaving would put them in a worse situation.

We can’t leave because things there are worse. Venezuela is going to get even uglier. Here Venezuelans have things to eat, and we can buy diapers and things for our son.

—Carlos, a Venezuelan in Peru

Family members who are in Venezuela encourage their relatives in Peru to continue fighting and enduring. The remittances these families receive from relatives in Peru allow them to access commodities and services that are scarce in Venezuela. These networks also ensure that those in Peru are aware of what is happening in Venezuela, which may discourage them from returning.

We would like to [return] because back there I have my family, and I am very close to my family. We have the hope of going back, but we see it as very difficult because the situation gets more complicated. Many people are leaving there. And here, I help myself as much as I help those back home. With what I send them they can cover their costs. We want to go back, yes, but it is hard. We will have to endure.

—Margarita, a Venezuelan in Peru

However, many Venezuelans in Peru simply cannot sustain themselves in Peru any longer, and the pull towards home is too great. Earlier in the pandemic, 30,000 Venezuelans left Peru to return to their home country in the hopes of seeing family again and returning to homes they have left behind.

Government Response

Humanitarian Assistance during COVID

The Peruvian government provides little humanitarian assistance to Venezuelan communities, preferring to leave this responsibility to international organizations. There are some notable exceptions, such as the Municipal government of Lima’s program called Casa de la Mujer for victims of gender-based violence, which are open to Peruvians and Venezuelans alike. The Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations (MIMP) announced that five new Special Protection Units (UPE) will provide specialized assistance in five departments to children and adolescents at risk or without parental care, including Venezuelans. The MIMP also confirmed the availability of 24-hour assistance for cases of gender-based violence. The Ministry of Education’s, Aprendo en Casa is accessible to Venezuelan and Peruvian children alike.

Venezuelans are not included in Peru’s COVID-19 response and recovery strategy and often are left out of international funding for the pandemic. The IMF approved a two-year arrangement for Peru under the Flexible Credit Line (FCL), designed for crisis prevention, of about US$11 billion. In March of 2020, Peru began putting together a stimulus package of USD $26 billion from various funding sources, including the IMF, to revive the economy and protect those most affected by the pandemic. The cash transfer program will provide recurring stipends of 380 soles (USD $106) to the country’s poorest 3 million families. This measure does not, however, extend to Venezuelans, even though many of them are poor. None of the Venezuelans that Encuentros SJM and Refugees International interviewed described government assistance when asked if they had received help during the pandemic. The majority received humanitarian support from local NGOs, UNHCR, churches, and Venezuelan-led organizations.

Excluding Venezuelans from government pandemic planning places Venezuelans at a larger disadvantage compared to the Peruvian population. As a result, Venezuelans become dependent on limited international humanitarian assistance, given their exclusion from government services. It will be particularly important for Venezuelans to be able to access the COVID-19 vaccine. The virus does not recognize nationality, and until most people in Peru are protected from the virus, COVID-19 will remain a threat.

Peru purchased its first batch of COVID-19 vaccines in January of 2021 and began vaccinating citizens with 300,000 Chinese Sinopharm doses in early February. President Sagasti stated that the vaccines will first go to healthcare workers and the most vulnerable of populations, and Peru’s Minister of Foreign Affairs said the government is contemplating providing doses to Venezuelans. However, the timeline is unclear as to when Venezuelans would receive these doses. The government signed an agreement to buy an additional 13.2 million vaccine doses through the COVAX Facility, a group led by the World Health Organization and other institutions. Sagasti confirmed the country paid a first installment to COVAX, which was established essentially to ensure access to vaccines in countries with limited capacity to purchase vaccines. It is unclear whether these COVAX facility doses would also be distributed to Venezuelans.

Avenues to Regularization

Apart from asylum, Peru has used a series of instruments to offer Venezuelans the opportunity to regularize their status. Many provide a temporary regular status and include the right to work. However, due to border closures, policy changes, bureaucratic hurdles, and political backlash, it can be quite difficult for Venezuelans to regularize their status. These barriers push Venezuelans into precarity, particularly during the pandemic when accessing health services, education, and humanitarian assistance are crucial to protection.

In October 2020, the government issued a decree aimed at regularizing Venezuelans already inside Peru and providing them with work permits. Once it is implemented in the coming months, the Temporary Stay Permit License (Carnet de Permiso Temporal de Permanencia or CPP) will serve as an extension of the PTP, aimed at people who have entered Peru irregularly or whose documents have expired after entering the country under a tourist visa. This documentation is certainly a step in the right direction. However, this status is valid only for one year, with no path to a more permanent arrangement. The CPP also requires a passport or other international travel document, which is difficult for most Venezuelans to obtain. According to interviews Refugees International and Encuentros SJM conducted with key stakeholders, bureaucratic hurdles, such as the capacity of the online platform and sufficient personnel to process these documents, are also of concern.

Another, perhaps more promising option is Humanitarian Residency (Calidad Migratoria Humanitaria). This visa would provide Venezuelans with broader protections than the CPP and allow for a path to permanent residency after three years of continuous stay in the country. Those with humanitarian residency are also issued a carnet de exranjeria, which is a widely recognized residency document that would facilitate access to health services and employment. It also protects the holders from deportation. This humanitarian residency can only be obtained at a Peruvian consulate in Venezuela or specific consulates in Colombia or Ecuador. This residency is granted as a humanitarian visa. However, key refugee advocates in Peru are calling for this option to be made more widely available to Venezuelans already inside Peru as well, especially for asylum seekers waiting for their cases to be resolved. This option would go a long way towards ensuring Venezuelan inclusion into the country and would provide a crucial safety net during the pandemic and the post-pandemic recovery.

Border Closures

On January 26, 2021, the Peruvian government militarized the northern border of Peru in an attempt to strengthen its border security and control irregular flows of Venezuelans into the country. Negative perceptions of Venezuelans are fueling xenophobia in the country ,and there is significant political pressure to stop migration into the country, particularly during the pandemic. Moreover, in the run-up to Peru’s presidential elections, it is concerning that some presidential candidates state they will deport irregular Venezuelans without due process, which contributes to this growing xenophobia and could bode negatively for Venezuelans.

While migration management is important to promote regular entry into the country, particularly during the pandemic, the border militarization is concerning to many activists who see this increased military presence as a risk to the human rights of migrants and refugees. The Peruvian Human Rights Ombudsman cautioned the Peruvian government to abide by Peruvian laws regarding the use of force against migrants and called on the government to ensure migrants can access the asylum process. Militarization of the border may prohibit Venezuelans who are seeking to enter Peru during the pandemic and deny them access to much needed refuge—pushing many to enter by irregular or dangerous routes.

Civil Society and International Organization Response

The GTRM was established at the request of the Secretary General of the United Nations to UNHCR and IOM on April 12, 2018, to lead and coordinate the response to refugees and migrants from Venezuela across the region. Operating at the regional and national levels, the GTRM aims to provide a comprehensive response in Venezuelan host countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Peru, the GTRM is made up of more than 80 organizations, including national and international non-governmental organizations, religious organizations, academics, embassies, donors, and financial institutions. Each of these organizations provides humanitarian support to Venezuelans in Peru.

In 2019, the funds required for the Regional Refugee and Migrants Response Plan (RMRP) for Peru was USD $106.2 million, which increased to USD $136.5 million in 2020, reflecting the growing need for support during COVID-19.

During the pandemic, the response from the GTRM has increased to continue providing the assistance to Venezuelans, as their humanitarian need has grown.

According to the GTRM Peru report in December 2020, the response scaled up to support several key sectors. Survivors of gender-based violence received case management and referral to specialized services. Some 800 people had access to food through 12 soup kitchens, and another 11,300 people received food kit assistance. In addition, a total of 1,110 people benefited from cash-based interventions (CBI) for livelihoods, a type of assistance that has been crucial during the pandemic to ensure Venezuelans can pay for necessities they may not otherwise be able to afford. GTRM partners provided primary health care to 1,000 refugees and migrants and members of the host community, including people living with HIV. Some 900 received CBI to access health and treatment services.

Although the response has grown, it is still not enough to meet the needs of Venezuelans. Furthermore, Venezuelans who participated in interviews with Encuentros SJM and Refugees International expressed their lack of information about the presence of civil society organizations or how to access them to request help. Additionally, some respondents did not have internet to access information circulated online. Despite these limitations, church organizations were the most visible in providing support during the emergency. Interviewees received in-kind donations such as food and hygiene supplies from various churches.

There is a Christian church around the corner. They give us groceries, a kilo of rice, spaghetti, milk, things like that.

—Maria, a Venezuelan in Peru

Besides the church, most interviewees stated they knew of organizations such as Encuentros SJM and UNHCR not from direct outreach, but through friends and acquaintances who had managed to contact these organizations and receive support. This allowed some of the interviewees to get in contact with UNHCR and Encuentros SJM and be registered to receive assistance and information regarding humanitarian and legal support. Through these organizations, they managed to obtain financial assistance that allowed them to cover needs and debts that had been generated during the quarantine.

Through WhatsApp groups, with friends who are most involved, they share through social networks. And we circulate them to others.

—Ronald, a Venezuelan in Peru

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for all of Peru, and especially Venezuelans living in Peru. One year into the pandemic, Venezuelans need humanitarian support, including shelter, healthcare, education, protection, and food. Apart from their basic humanitarian needs, Venezuelans desperately need access to regularization mechanisms so that they can live without fear of being returned to Venezuela and to be able to participate both in the COVID-19 response and recovery. While civil society organizations are doing incredibly important work to keep the Venezuelan population afloat, without broader support from the government and international donors, Venezuelans will continue to be at a disadvantage during and long after the pandemic.

Recommendations

To the Peruvian Government:

- Include Venezuelans in the national COVID-19 Response and Recovery Strategy and permit vulnerable Venezuelans to benefit from the government’s COVID-19 cash-based initiatives, which would safeguard them from food insecurity, street work, and eviction. As part of its pandemic response, the government should also include direct service provision to Venezuelans, such as broader access to COVID-19 related healthcare.

- Improve information campaigns and outreach strategies to Venezuelans to ensure that they are aware of government services like “Aprendo en Casa.” Work with civil society organizations that have close relationships with Venezuelan communities and with Juan Guaido’s Ambassador to Peru to circulate information on this campaign.

- Ensure that the COVAX facility vaccines are provided equitably to Venezuelans in Peru by assessing the number of Venezuelans in need of vaccination, providing registration to Venezuelans for the vaccine, and ensuring that vaccine rollout is distributed to health centers who treat the most high-risk populations.

- Enable beneficiaries of the new regularization (CPP) the ability to apply for longer-term residency, such as special resident immigration status, following the one-year expiration of their CPP. Longer-term status will provide greater security to Venezuelans as well as a wider enjoyment of services.

- Allow for Venezuelans inside Peru to apply for Humanitarian Residency.

- Keep the border open for people seeking international protection. Ensure the rights of Venezuelans are protected at the northern border by providing oversight mechanisms for the border agents and military personnel deployed, including monitoring from the Human Rights Ombudspersons office. Increase civil society presence at the border to provide additional support to those who wish to seek asylum or apply for a humanitarian residency.

To the International Donor Community:

- The current RMRP response is currently funded at 47 percent. International donors should scale up support for humanitarian aid to Peru through the GTRM and give priority to underfunded sectors such as protection, health, and shelter.

- International financial institutions should include earmarked humanitarian assistance for Venezuelans and equitable vaccine distribution as part of aid packages given to the Peruvian government.

To Civil Society:

- Expand informational campaign efforts to reach more Venezuelans. Work with Venezuelan-led organizations to ensure messaging about services is made more widely available to the Venezuelan community.

Endnotes

1 Encuentros SJM, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Protection Monitoring in Peru”. October and November 2020

2 Ibid

PHOTO CREDIT: Venezuelan family in the district of San Juan de Miraflores, Peru 2021. (Photo by Encuentros SJM)