“They Left Us Without Any Support”: Afghans in Pakistan Waiting for Solutions

Executive Summary

An estimated 600,000 Afghans have fled into Pakistan since the Taliban ascension to power in Afghanistan in 2021. At least 2.2 million unrecognized.1 Afghans now live in Pakistan without legal status or protection in the country, in addition to at least 1.32 million registered and recognized Afghan refugees, many of whom have been in the country for decades. A considerable portion of the recent arrivals are women and girls who fled targeted threats and a general stripping away of their rights in Afghanistan. The unregistered Afghans – unable to obtain legal status in Pakistan but unable to safely return to Afghanistan – present a growing but officially unacknowledged dimension of the Afghan refugee crisis. Meanwhile U.S. commitments made two years ago to resettle Afghans via P-1 and P-2 resettlement programs remain stalled due to Pakistan-U.S. policy disagreements – even as other countries have been successfully resettling some Afghans out of Pakistan. This paper outlines potential solutions to break the apparent impasse and begin taking measures to protect vulnerable Afghans in Pakistan.

Although the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan is fenced and guarded, the Pakistani authorities often turn a blind eye to Afghans entering Pakistan undocumented or with visas purchased on the black market. Pakistani authorities are unwilling to record even basic information about these hundreds of thousands of recent Afghan arrivals. This neglect and lack of official recognition leaves these unacknowledged refugees insecure.

The situation is particularly frustrating and precarious for Afghans at risk of reprisals from the Taliban. Ample reporting has documented the Taliban targeting human rights defenders, women’s rights activists, former Afghan government officials, members of the Afghan military, LGBTQ+ people, ethnic minorities, and others. The Taliban continue to issue increasingly draconian restrictions on women’s participation in public life in Afghanistan, culminating with the most recent bans on women working for non-governmental organizations, and even the United Nations. That, coupled with a worsening humanitarian situation, has left many Afghans who fled to Pakistan since 2021 with no good options and certainly no possibility of returning to Afghanistan anytime soon.

An estimated 20,000 of the 600,000 newly arrived Afghans in Pakistan have referrals for resettlement to the United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) through Priority 1 (P-1) and Priority 2 (P-2) categories. P-1 is for people “known” by the former U.S. Embassy in Kabul and referred by a U.S. official for resettlement. P-2, a new program the State Department announced in the beginning of August 2021, is for Afghans who worked for a U.S.-based NGO or media organization that refers them. To be processed for resettlement, these individuals must be outside of Afghanistan. It is possible to resettle those people whose cases meet the criteria and pass security and medical checks. But, despite the fact that many of these individuals spent their careers working alongside people from the U.S. mission—who have similar goals for human rights and democracy in Afghanistan—the United States has not begun processing their cases due to an apparent stalemate with Pakistan over how to process them.

Nearly two years after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, the promise of the P-1 and P-2 resettlement programs in Pakistan have gone unfulfilled. The State Department explains that resettlement from Pakistan is at a standstill because the Pakistani government will not permit the establishment of a Resettlement Support Center (RSC) in the country. The government of Pakistan is reportedly concerned that this could encourage more Afghans to enter Pakistan. The United States indicates that an RSC in-country is a requirement for the movement of cases out of Pakistan.

Yet, there are alternatives that the United States could pursue that could allow resettlement to continue while the United States and Pakistan are engaged in bilateral negotiations over the establishment of an RSC. The State Department has been tight-lipped about precisely why it has suspended all resettlement referrals while other countries are still managing to resettle small numbers of cases from Pakistan. The United States must not let the perfect be the enemy of the good; if there are any means of continuing resettlement while RSC negotiations continue, those must be maintained. The complete lack of resettlement to the United States from Pakistan and lack of clarity on any progress towards that goal is unacceptable and dangerous for Afghans. To date, the United States is failing to live up to the commitments it made to protect Afghans through its P-1 and P-2 programs.

This report outlines the overall landscape for Afghan refugees in Pakistan and the conditions they face. It focuses heavily on Afghans who have fled to Pakistan since August 2021, especially women and girls who cannot return to Afghanistan but face risks and challenges in Pakistan. The report urges the Pakistani government to expand protection and services to all Afghans in their territory and allow the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and NGOs to assist all Afghans, not just recognized legacy refugees. The report also highlights obstacles to processing P-1 and P-2 cases and potential solutions to alleviate them. Afghans with P-1 and P-2 referrals constitute a manageable caseload. The U.S. government gave them hope of resettlement, and they are already in the resettlement “pipeline.” They have no rights in Pakistan and are at risk of deportation back to Afghanistan, where they could be killed. Therefore, the United States should shift its processes to consider all possible options to support Afghans seeking safety, even if an RSC cannot be established.

Recommendations

The government of Pakistan should:

- Become a signatory to the Refugee Convention and develop corresponding national asylum and refugee legislation that provides a framework for receiving, registering, hosting, and integrating refugees.

- Register undocumented Afghans and provide them with Proof of Registration (PoR) cards that would offer them greater freedom of movement and access to public education, healthcare, and bank accounts. Registration would enable more effective assistance to all Afghans and facilitate the resettlement of Afghans to other countries.

- Allow the UNHCR and NGOs access to all Afghans in Pakistan, including new arrivals and currently undocumented individuals.

- Permit the United States to establish an RSC in Pakistan. If necessary, authorize a temporary RSC to operate for an agreed-upon time frame, such as three to five years. Allow enough time for the United States to process P-1 and P-2 cases in Pakistan that already have assigned case numbers.

- Provide exit permits for Afghans to leave Pakistan for resettlement processing to the United States through other sites such as Camp As Sayliyah (CAS) in Doha, Qatar.

The United States government should:

- Consider alternate RSC models if agreement cannot be reached to establish one in Pakistan. A regional RSC, potentially in Tajikistan or Nepal, could serve Afghans in South and Central Asia, including those in Pakistan. While Pakistan may object to a larger U.S. government footprint within Islamabad, a regional RSC could still begin processing cases.

- Utilize the CAS model of specialized, concurrent processing for any new RSC to improve efficiency. This would ensure staff from all the relevant U.S. agencies are in one location and complete processing steps at one time rather than sequentially.

- Conduct initial United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) interviews with Afghan refugees in host countries virtually to further expedite processing.

- While setting up an RSC, immediately prioritize processing resettlement cases of at-risk Afghan women with P-1 or P-2 cases in Islamabad by relocating them temporarily to CAS or elsewhere. The United States can use these initial groups of women and their families as test cases from which the United States can grow a more extensive program.

- Utilize the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad to process small numbers of cases within Pakistan. This would ensure some cases are processed while also being discreet, alleviating some of the government of Pakistan’s concerns.

- Communicate more consistently and clearly with Afghans in Pakistan with pending P-1 and P-2 cases about the current state of their individual cases.

- Provide clear and accessible public information about the overall state of the Afghan USRAP program, including processing times, approval rates, and a gender breakdown of applicants. This information will allow policymakers to increase oversight, improve efficacy, and guide additional resources to different pathways.

The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Pakistan should:

- Press the government of Pakistan to register and recognize undocumented Afghans by issuing them Proof of Registration (PoR) cards. UNHCR should provide technical support, financial support, and capacity building to the government of Pakistan to undertake this effort.

- Expand refugee-focused services outside of refugee villages to urban areas where they can serve additional undocumented refugees with services such as livelihoods programs, educational programs, and mental health and psychosocial support programs.

- Meet with Afghans who entered Pakistan since August 2021 to assess their living conditions, document their protection concerns, and work with NGO partners to develop programs tailored to their needs.

International donors should:

- Increase financial support to the UN’s Afghanistan Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan (RRP) and UNHCR Pakistan so that UN agencies and their partners can address the needs of the growing numbers of Afghans in the country. Require that some of the funding support the government of Pakistan’s Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees and be used for programs that target undocumented Afghans, especially new arrivals.

- Provide flexible funding for humanitarian aid to Pakistan to encompass assistance to newly arrived refugees in urban areas and support local NGOs.

- Press the government of Pakistan to allow registration of all Afghan refugees and issuance of PoR cards so that they are afforded rights and can more easily access NGO and UN agencies services.

Methodology

A Refugees International team traveled to Islamabad, Pakistan, in April and May 2023. The team met with Afghans who entered Pakistan since August 2021 and representatives of UNHCR, NGOs who work with refugees,2 the government of Pakistan, and the U.S. government.

Refugees International met with a number of Afghan women and girls of varying ages and from various regions in Afghanistan. The team also met with Afghan men, most of whom served in the former Afghan government. Many Afghans the Refugees International team interviewed had been referred to the P-1 or P-2 programs for resettlement, some were awaiting the issuance of Special Immigrant Visas (SIV) for those who worked for the U.S. military in Afghanistan, and some did not have any current prospect for resettlement. All the refugees the team interviewed live in Islamabad or neighboring cities.

Refugees International also traveled to Doha, Qatar, and met with U.S. government officials from the U.S. Mission to Afghanistan.

Background: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

Pakistan has long been home to a vast number of Afghan refugees. At times, it hosted the largest number of registered refugees in the world. Pakistan started accepting Afghan refugees following the beginning of the Soviet-Afghan war in 1979, reaching between 3.2 and 4 million by 2001. Many of those refugees returned home over the years, but millions remain, and new refugees have arrived since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021.

Legal Status

Pakistan is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees

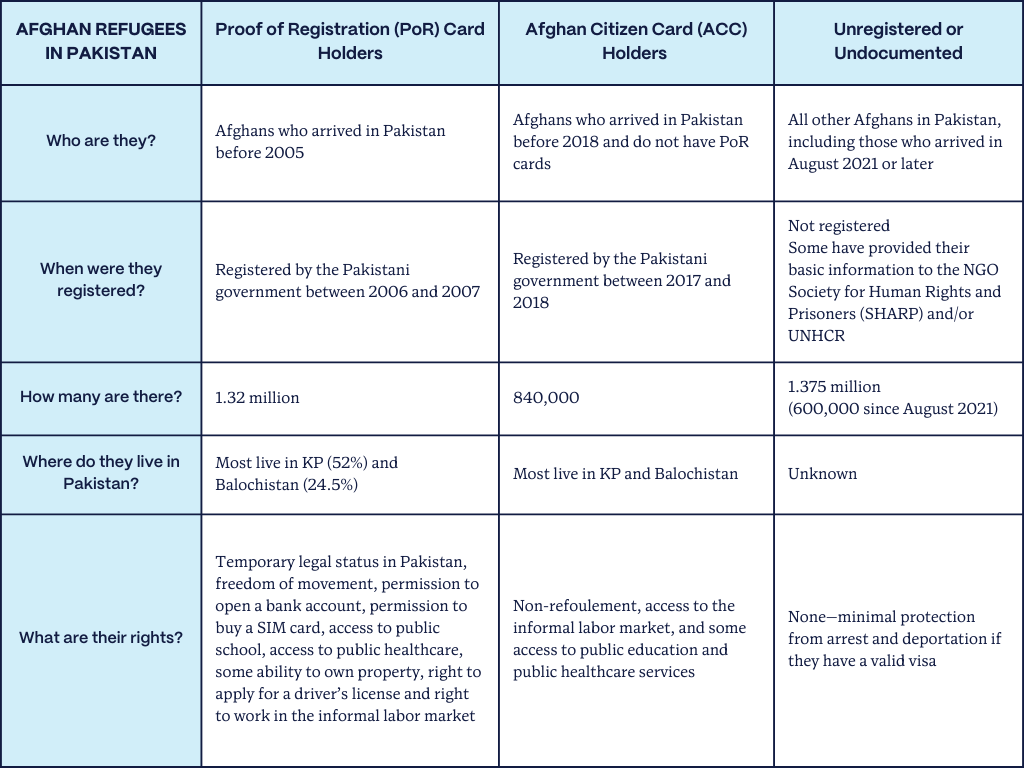

or the 1967 Protocol. Nor has the country passed any national refugee or asylum legislation. However, between 2006 and 2007, together with UNHCR, the Pakistani Ministry of States and Frontier Regions (SAFRON) registered Afghans in Pakistan and issued them Proof of Registration (PoR) cards. According to the UNHCR Representative in Pakistan Noriko Yoshida, “They provide proof of identity, entitlement to temporary stay in Pakistan, and freedom of movement. They facilitate access to certain essential services, including education, healthcare, banking, property rental, and allied facilities.”

Pakistan’s National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) and the Chief Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees conducted verification exercises with the support of UNHCR in 2010, 2014, and 2021 (completed in January 2023) to update the numbers of PoR card holders. But apart from issuing new cards to children born to PoR card holders and a few unregistered family members of PoR cardholders, no new cards were issued; the Pakistani government only updated the registration information they had initially collected in 2006 and 2007. These are the only Afghans the Pakistani government recognizes as refugees, comprising about 1.32 million people.

In 2017, the Pakistani government created the Comprehensive Policy on Voluntary Repatriation and Management of Afghan Nationals, by which—in a joint exercise with IOM and the former Afghan government—they issued Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC) to about 840,000 undocumented Afghans in Pakistan. This card confirmed the Afghan citizenship of its bearer. It also ensured that the government of Pakistan had Afghans’ basic information and allowed them to stay in Pakistan—but came short of considering them “refugees.” All other Afghans without PoR cards or an ACC have no status and, therefore, no legal protection from refoulement.

The only Pakistani legislation related to refugees is the Foreigners Act of 1946 and the Foreigners Order of 1951. According to these laws, all foreigners without valid documentation are subject to arrest, detention, and deportation. Thus, unless they have current visas, most of the 600,000 plus newly arrived Afghans who entered Pakistan since 2021 are at risk of being deported back to Afghanistan.

According to some Pakistani officials themselves, the government has been very slow to respond to the fall of Kabul and Afghan refugees arriving. By December 2021, the Pakistani government was still discussing where reception centers should be located. UNHCR said in a statement that since 2021, they “have been in discussions with the Government of Pakistan on measures and mechanisms to support vulnerable Afghans. Regrettably, no progress has been made.” The Pakistani government has even instructed UNHCR, which previously issued Afghans with asylum-seeker certificates, to discontinue meeting with new arrivals to issue them any form of documentation.

And it is not just refugees who fled to Pakistan after the fall of Kabul who have no protection. The government of Pakistan continues to defer a decision on whether they should register any Afghans who arrived after 2017 when they stopped issuing ACCs. One official told Refugees International, Pakistan “is just kicking the can.”

It is important that the Pakistani government register undocumented Afghans, including new arrivals. Registration is essential for security, management, donors, and future policy decisions. Furthermore, the government should issue PoR cards to undocumented Afghans and those with ACCs. This will allow Afghans to access more services in Pakistan and more easily contribute to the Pakistani economy. If the Pakistani government registers as many Afghans in the country as it can, it can conduct basic interviews to determine which Afghans are refugees. Knowing the true number and basic details of refugees in the country will be more of an impetus for donors to support Pakistan’s assistance to and integration of these refugees.

Limited Humanitarian Assistance

The humanitarian aid groups in Pakistan that serve refugees focus on the population of refugees who hold PoR cards. While the government of Pakistan and UNHCR track and report refugee assistance, they usually capture data from PoR card holders specifically, not encompassing new arrivals or other Afghans who do not have documentation. A country director for an international NGO that serves refugee populations estimated that 90 percent of their work has been in rural settings with PoR card holders. This failure to acknowledge the presence and needs of newly arrived refugees is a major protection and assistance gap and contributes to extreme vulnerability.

The lack of status and dispersion of newly arrived refugees in urban areas presents multiple challenges for delivering humanitarian aid and services. It is also difficult for organizations to find accurate data on who is living in Pakistan. Furthermore, uncertainty and lack of formal status beget mental distress for an already traumatized population. A few international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) have been able to provide mental health services to some newly arrived refugees. But without registration data or permission from the Pakistani government to create programs specifically for this population, it is difficult to access them.

Additionally, Pakistan is a challenging operating environment for INGOs. “INGOs are under surveillance generally, and those who are working with refugees more so,” an INGO staff member said. The added scrutiny provides little room to advocate on behalf of refugees—especially those who are undocumented—within the country. He continued,

Pakistanis have always looked at [the refugee situation] from a security lens, not as a humanitarian matter…looking at it from a humanitarian perspective…is what is needed.

INGO Staff Member in Pakistan

Lack of sustained, sufficient funding and support is another persistent issue. In 2023, the UN requested about U.S. $384 million for Pakistan through the Afghanistan Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan (RRP). To date, 95.4 percent of the funding for the entire RRP is unmet. In 2022, the RRP was funded at only 22.5 percent, far below UNHCR’s global funding level of 52 percent, raising fears that the funding for the 2023 RRP will again fall far short of its needed amount. The founder of a prominent Pakistani NGO described that they had to close a women and children’s shelter for Afghans several months ago due to a lack of funding. Other NGOs told Refugees International that it is difficult to provide the services that Afghans need when they must constantly solicit donors who have other priorities.

Historic flooding in 2022 added to the humanitarian needs across the country. Afghan refugees were also affected, with more than 421,000 refugees living in the worst affected districts, including Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) Province and Sindh Province. Nearly six months after the catastrophe, more than 10 million people in Pakistan still lack access to clean water while the country is bracing for additional flooding this year.

Although most refugee-related funding serves PoR cardholders, some INGOs and national organizations can serve newly arrived populations along with PoR cardholders through community-wide programs like water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) or other healthcare services, especially in rural areas. This becomes even more possible when INGOs have the funding flexibility to serve a wide range of beneficiaries. The government of Canada, for example, provides flexible, unearmarked funding that allows general humanitarian funding also to include assistance for new arrivals. The United States and other donors should prioritize flexible funding to UN agencies and NGOs working with Afghan refugees in Pakistan.

Detention and Deportation

Almost all of the Afghan refugees who met with Refugees International in Islamabad and Rawalpindi arrived in Pakistan soon after the fall of Kabul in 2021. Several families told Refugees International that they sold their homes and belongings to fund their lives in Pakistan, but that money was running low nearly two years into their time in the country. Refugees described paying under-the-table to receive Pakistani tourist, student, or medical visas initially. Many of those visas were short-term in nature and have since expired. Several people told the Refugees International team that the only way they can extend their visas is to pay a middleman between U.S. $700 and $1,000 for a three-month renewal. Families with financial resources can renew visas, but many have expired documentation. Those with expired visas feel high anxiety and instability about their precarious situation. The fear of deportation or detention keeps them from venturing outside often or trying to access hospitals or markets.

Although there has been a large population of Afghans in Pakistan for a long time, xenophobia toward Afghans is growing. Pakistan is struggling with economic instability, intensifying internal polarization, and renewed extremism along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Most of the Pakistanis Refugees International spoke to noted that there has been greater tension between Pakistanis and Afghans in the last few years than they remember. The head of a refugee-focused NGO in Pakistan said, “Overall, Afghans and Pakistanis live in peaceful co-existence and have for a long time. But now, more Pakistanis are tired of having so many Afghans in the country when there are so many problems in Pakistan already. Discrimination is increasing.”

Several young Afghan men described Pakistani police arresting them when they were trying to find informal work to help support their families or even when they were just out of the house. One man in his twenties explained, “I have been arrested and detained multiple times. When the police see more than two or three Afghan men together, they are immediately suspicious and harass us for our papers. But we can’t afford to renew the visas, so what do we do?”

Expired visas make newly arrived Afghans feel insecure and uneasy. One Afghan woman with a P-2 case said. “While I don’t fear day-to-day as much as I did in Afghanistan, I do fear I could get deported because my Pakistani visa has expired. I can’t go back to Afghanistan. I would be killed.”

All of the women Refugees International spoke with said they are horrified by the increasing restrictions on women in Afghanistan. They are glad they are not living under prohibitions they recognize as “inhumane.” However, they explained that in Pakistan, they fear violence or abuse with no accountability. “In theory, we can go outside in Pakistan, so it is different than Afghanistan in that way. But we are afraid that if something happens to us—let’s say we are attacked, robbed, or raped—who will come to our aid? How would there be any justice? We are not citizens here. We are not even refugees here. No one will register us,” one woman lamented. Another woman added,

We are invisible here, and we have been forgotten.

Afghan Woman Refugee

“During 20 years, we [were] working closely with the United States; we had joint goals and joint operations. When we got in a bad situation, they left us without any support,” one former high-ranking government official and P-1 applicant said. “For more than six months, I was afraid here and did not leave my rooms,” another refugee living in Rawalpindi said.

The fears of detention and deportation are well-founded. In recent months in Sindh Province, there have been reports of increased detention of Afghan refugees. Lawyers representing Afghans have said that there were around 800 Afghans in detention across Karachi and Sindh Province. While the government of Pakistan has said they are only detaining “criminals,” others report that Pakistani authorities have detained documented and undocumented Afghans. A crackdown in June 2023 in Islamabad and Rawalpindi resulted in official reports of 300 to 400 Afghans being detained. An Afghan living Rawalpindi told Refugees International it is more than 500.

Pakistan has also increased deportations of Afghans in recent months. In January, over three days, more than 600 Afghanswere expelled back to Afghanistan from Sindh Province. There were also reports that Pakistani authorities expelled more than 1,400 Afghans from Karachi and Hyderabad since October 2022. As a proportion of the number of Afghans in the country, these numbers are not very high. But they function as a fear tactic, and the threat of detention and deportation keeps Afghans in constant distress. In Rawalpindi, Afghans told Refugees International of regular searches from police forces in their apartments.

It is essential that the Pakistani government reconsider registering undocumented Afghans, including new arrivals. The government would have the necessary knowledge about who is in the country, and Afghans could feel more secure. With at least some form of documentation, Afghans would have less fear of arrest, detention, or deportation. UNHCR should be much more robust in its advocacy to this effect. Several refugees and NGOs expressed significant frustration that UNHCR has not been more forceful in its efforts to ensure Afghan refugees in Pakistan are registered and protected in line with its mandate.

An Afghan man with a P-1 case and an expired Pakistani visa who previously worked for UNHCR in Afghanistan said, “UNHCR is meant to help refugees, and we are refugees. They might help Afghans in other parts of the country, but in Islamabad, we do not know what they are doing.” UNHCR is engaged in significant work directly and through its implementing partners throughout the country. But it is in a difficult position in Pakistan because the Pakistani government only allows UNHCR to implement programs for legally recognized refugees and to some extent Afghans with ACCs. UNHCR is understandably concerned that pressing the Pakistani government more forcefully to provide more rights to all Afghans could jeopardize its other operations in the country. But this inherent tension exists in many other countries and cannot be justification for inaction. UNHCR is responsible for advocating for refugees, including Afghans, who are currently denied status. UNHCR needs to be an institution that more refugees, especially newly arrived Afghans, see as their ally. It can start by meeting with undocumented Afghans and learning more about their needs and concerns so that they can advocate on their behalf.

Lack of Opportunities

The Afghans who spoke with Refugees International consistently cited their most pressing challenges as lack of access to education for their children, inability to work in the formal sector, and rising costs in Pakistan for necessities like rent, food, and healthcare.

Education

About 50,000 ACC or PoR cardholders, whose status permits them to access public education, are enrolled in school in Pakistan—mostly in provinces with more integrated refugee populations. However, this does not apply to newly arrived Afghans because the government does not consider them to be refugees. The lack of access to formal schooling in Pakistan is highly concerning to Afghan parents with whom Refugees International met. Many have been unable to enroll their children in formal schools since 2021. Instead, some have resorted to putting together makeshift groups of students with community members volunteering to be teachers. But most young Afghans who arrived in Pakistan recently do not attend school at all.

A 15-year-old daughter of a former female Afghan politician attended an international school in Afghanistan until she was in the ninth grade and the Taliban took power. After fleeing the country, she has not been in school in Pakistan. “I have lost all of my hopes and ambitions. It really stresses me out to think that I don’t know where I can live a real life. It seems as though nobody wants us,” she said.

Livelihoods

Undocumented Afghans have few opportunities to earn a living and cover the costs of their basic needs. PoR cardholders, and to some extent Afghans with ACCs, can work informally without the fear of police harassment or government interference, in theory. PoR card holders can start businesses selling handicrafts or food because they can open bank accounts, obtain driver’s licenses, and have less fear of deportation. Yet in practice, they are still vulnerable to harassment from police. Newly arrived Afghans, with even less security and access to services, are generally unable to start businesses or work. Some Afghan men take labor and construction jobs, but whatever work they can find is often in high-risk, unsafe environments where they are subject to exploitation and abuse.

An Afghan woman who worked in the former government in Afghanistan told Refugees International,

We cannot work here, and we are running out of money. Most of us have only survived this long because friends and relatives send us some money from abroad. I used to have a good and important job. I am nothing in Pakistan.

Afghan Woman Refugee

Healthcare

Afghan PoR and ACC holders have access to public hospitals and doctors free of charge, on par with Pakistani nationals. The government also includes them in government-sponsored healthcare programs such as immunization campaigns and HIV prevention and treatment programs. While the quality of the public healthcare system in Pakistan is generally low, cardholding Afghans can receive basic medical care. The Pakistani government should be applauded for this inclusion of some refugees.

Newly arrived Afghans, however, who are virtually all undocumented, technically cannot access the public healthcare system. In practice, public hospitals do not often check documentation, and Afghans are usually not turned away. But most Afghans Refugees International spoke with in Pakistan do not want to risk approaching a public institution without a valid visa. Therefore, they resort to private doctors, which are expensive. And there are few, if any, additional health service support programs implemented by NGOs for this population. Therefore, the rising costs of healthcare services paired with Afghans’ inability to work leads to an untenable situation for many.

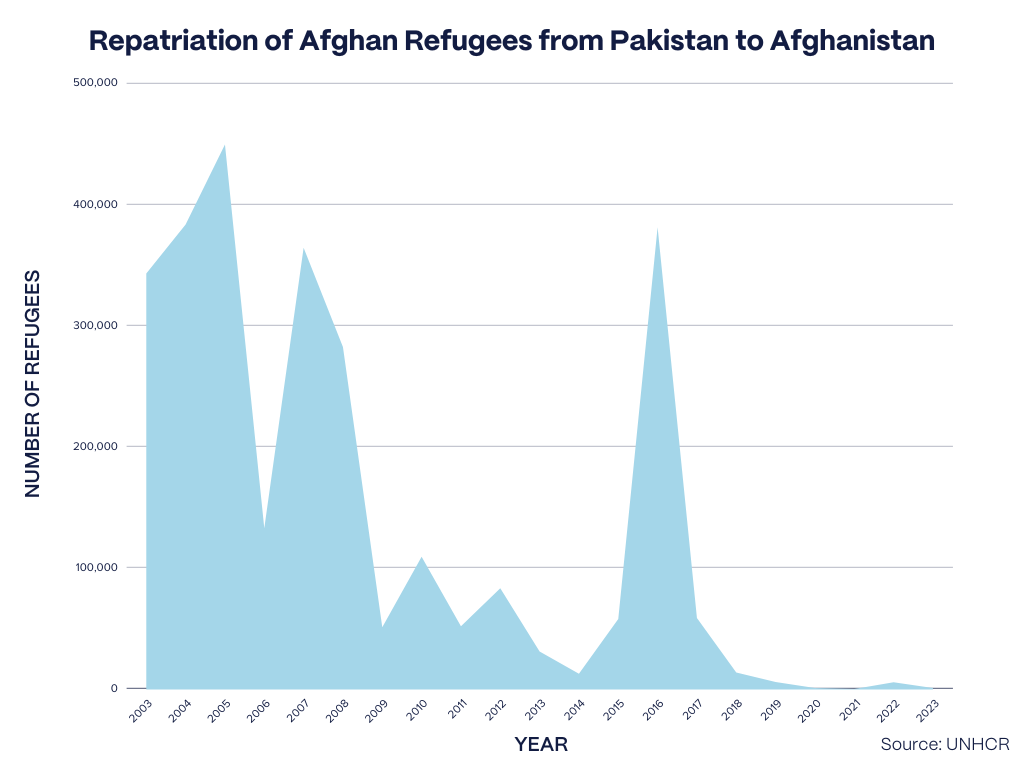

Limited Options for Return

Some Afghan refugees in Pakistan have returned to Afghanistan in recent years. All told, since 2002, UNHCR has assisted 783,617 households comprising 4.38 million Afghans with voluntary repatriation or assisted voluntary returns (ARVs). However, currently, few are going back. From January to March 2023, only 1,255 people voluntarily returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan with the assistance of UNHCR. Most of these returnees were Pashtun, and the vast majority lived in Balochistan and KP in Pakistan. Only 3 Afghans living in Islamabad returned to Afghanistan during this period. This meager number of returnees from Islamabad tracks with what Refugees International found during their trip.

Although the circumstances for undocumented Afghan refugees or, as the government of Pakistan refers to as “economic migrants” or “transit migrants” are very challenging, few of the newly arrived Afghan refugees—and none of the Afghans Refugees International met with in Islamabad—can safely return to Afghanistan.

Each of the Afghan women Refugees International spoke to in Pakistan detailed targeted threats the Taliban made towards them and their families. Most only stayed in Afghanistan for days, weeks, and, at most, a few months after August 2021. When they remained in Afghanistan, they were compelled to move houses every few days to avoid the Taliban locating them and attacking them as the threats they received suggested. Many of them were political leaders of the former Afghan government, including parliamentarians and senators. Most worked on human rights committees and gender-based violence-related initiatives through their public sector work. Therefore, as soon as the Taliban took over, they were directly at risk of reprisals and violence. One woman explained that because her mother had been a senator in the previous government, Taliban forces broke into the daughter’s home in Kabul, shot her, and left her for dead. She survived following major surgeries and is now in Pakistan.

In addition, these women and their families cannot return because the Taliban has systematically stripped away women’s rights to such an extent that it may amount to “gender persecution, a crime against humanity.” The European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) recently concluded that Afghan women and girls generally are at risk of persecution, and there is no “internal protection alternative,” meaning that there is nowhere within Afghanistan where women and girls are safe. With over 80 edicts denying women their fundamental rights, women and girls cannot engage in public life without risk of punishment. Afghan women and girls who defy these edicts have been beaten, arrested, detained, tortured, and sexually assaulted.

Furthermore, the economic and humanitarian situation in Afghanistan continues to degenerate quickly. The country’s economic output decreased by 20.7 percent in 2021, a remarkable downturn with widespread consequences. Refugees International traveled to Afghanistan in 2022 to witness some of these effects firsthand, highlighting the deterioration of the humanitarian crisis and the collapsing economy. In 2023, Afghanistan became the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, with more than 28 million Afghans (two-thirds of the population) requiring humanitarian assistance and 6 million people on the brink of famine.

Resettlement

The Pakistani government should find ways to work with the United States and other resettlement country governments to facilitate, not impede, the resettlement of these newly arrived Afghans who are at specific risk from the Taliban. The Government of Pakistan has demonstrated an unwillingness to even appear to be welcoming to recent refugees from Afghanistan and wants to discourage any increase in migration into the country. However, for Afghans fleeing specific threats to their safety since 2021, resettlement should be a viable option. Indeed, many of them qualify for resettlement in the United States according to the Priority 1 (P-1) and Priority 2 (P-2) case processing priorities. The U.S. Department of State (DoS) established these programs specifically for people who did not work directly for the U.S. government but whose work was related to U.S. interests and therefore are now at heightened risk from the Taliban.

Standard Practice

Typically, resettlement to the United States has a standard set of protocols. It usually starts with UNHCR or certain NGOs operating in host countries identifying the most vulnerable refugees who need resettlement and then writing case referrals for them. The referrals are based on at least one substantial in-person interview with the principal applicant and their immediate family members. Once UNHCR or the NGOs prepare the case referral, they send that information to the U.S. embassy.

At this point, the U.S. government gets involved and sends cases from the embassy to Resettlement Support Centers (RSCs). The DoS contracts with the International Organization of Migration (IOM) or NGOs to operate RSCs in various countries worldwide. Currently, RSCs are operational in Nairobi, Vienna, Bangkok, Warsaw, Amman, Istanbul, and San Salvador, with sub-offices in Pretoria, Kasulu, Kampala, Tel Aviv, Kuala Lumpur, Cox’s Bazaar, Chisinau, Cairo, Doha, Beirut, Quito, Guatemala City, and Tegucigalpa.

The RSCs pre-screen refugees, create files for each case, and prepare refugees for their interviews with Refugee Officers from the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (DHS/USCIS). The RSCs then host DHS/USCIS officers on circuit rides. During this time, they interview the refugees with case files and determine if they meet refugee admission criteria under Section 207 of the Immigration and Nationality Act. If the DHS/USCIS officer conditionally accepts the case, then the refugees’ information goes through security checks by various databases, the refugees undergo in-person medical checks, and ultimately IOM facilitates their travel to the United States.

Afghan P-1 and P-2 Programs

For Afghans, the resettlement process has been slightly different. Many resettlement cases are part of the P-1 and P-2 designation categories or processing priorities. P-1 cases are referred because of the individual characteristics of their claims, and P-2 cases are referred because they are part of a “group of special concern” designated by the Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM). As is true for standard resettlement, for cases in both categories, the refugees cannot refer themselves. They also must demonstrate that they are at risk in Afghanistan and need resettlement from where they are, whether in Pakistan or elsewhere. As noted in the section above, globally, UNHCR or NGOs usually refer cases to the State Department for resettlement. But for Afghans, most P-1 cases are referred by former employees of the U.S. Embassy Kabul and other U.S. government agencies or bureaus such as the Department of Defense (DoD).

Few Afghans are “known” to the former U.S. Embassy in Kabul. Therefore, the number of cases eligible for P-1 processing is limited. But because so many Afghans are at risk due to their relationship with U.S.-affiliated organizations or the media, two weeks before the fall of Kabul and as U.S. troops were preparing to withdraw from Afghanistan, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced the creation of the Priority-2 or P-2 designation. This program allows U.S. government agencies or U.S.-based NGOs and media organizations to refer former employees and their immediate families to the P-2 program. This was a welcome announcement and a crucial step to expanding the pathways by which at-risk Afghans could reach safety in the United States. Principal applicants of SIV cases predominately consist of male principal applicants. Creating this P-2 program was especially significant because it opened up the possibility for more Afghan women to access resettlement. However, the gender breakdown of the P-1 and P-2 program is not publicly available. The announcement of the program also demonstrated the U.S. government’s acknowledgment of its responsibility for the tens of thousands of Afghans it left behind during the evacuations but whose lives are at risk due to their work supporting U.S. priorities in Afghanistan. Secretary Blinken characterized these individuals as those “who helped us and deserve our help.” He acknowledged the “significant diplomatic, logistical, and bureaucratic challenge” of resettling the Afghans qualifying for this resettlement program.

Given these daunting challenges, it is important for more information on Afghan referrals to the United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) program be publicly available to provide clarity and guidance to refugees seeking safety as well as increase oversight for policymakers looking to improve the efficiency of the current resettlement process. As of July 2022, USRAP received P-1 and P-2 referrals for about 45,000 Afghans inside and outside of Afghanistan. But more recent data on the number of total P-1 and P-2 referrals is not available. Since October 2022, 3,584 Afghans have arrived in the United States through USRAP. A specific breakdown is not publicly available, but it is likely that most of these are P-1 and P-2 cases. While USRAP is mandated to provide some of this information to the U.S. Congress, they should make public additional information, including processing times, approval rates, and gender disaggregated applicant numbers.

Resettlement Case Processing in Pakistan

According to some estimates (the numbers are not public; therefore, a precise number is unknown), there are close to 20,000 individuals3 with P-1 and P-2 cases currently living in Pakistan pending processing. U.S. government officials, organizations, and media companies have also referred thousands of Afghans for resettlement who are still in Afghanistan. For example, one INGO with operations in Afghanistan has referred at least 500 individuals for the P-2 program who it has employed and are still in Afghanistan. This is another difference between traditional resettlement through the USRAP and the Afghan P-1 and P-2 programs since the Taliban takeover. People and organizations outside of Afghanistan can submit referrals for individuals still inside the country. But processing begins only after Afghans are in another country. This has led Afghans to cross the border to Pakistan. Large numbers of Afghan refugees have also entered Iran, which also borders Afghanistan. But the United States does not have diplomatic relations with Iran and therefore does not conduct resettlement case processing of Afghans from there.

Pakistan, then, is the natural choice for many Afghans who are unsafe in Afghanistan. Afghans can get to Pakistan via land borders, and the visas are less expensive to buy than for some other nearby countries. For example, one Afghan refugee in Islamabad cited that an Afghan trying to escape the country can buy a three-month Pakistani medical visa for as little as U.S. $600 per person. In contrast, visas to Tajikistan cost about U.S. $3,500 per person, and a visa to Türkiye costs at least U.S. $4,100. For most Afghans, these prices make leaving Afghanistan cost-prohibitive, or their only choice is to flee to Pakistan. Also, there is such a large population of Afghans already in Pakistan; they often expect they will be able to integrate more readily.

Furthermore, former and current U.S. officials, NGOs, and media companies submitting cases to the P-1 and P-2 programs explained to the Afghans they referred that they needed to leave the country to get processed. Afghans in Pakistan with P-1 or P-2 cases told Refugees International that “the U.S. government instructed me to go to Pakistan and promised me resettlement.” Many Afghans have misunderstood the possibility of resettlement through one of these pathways as a promise that they personally would be resettled. Some also consider the U.S. citizens who referred them to be speaking on behalf of the U.S. government.

Communication between the referring entities, the U.S. State Department, and the refugees must be more precise and consistent. And the U.S. government needs to be more realistic with refugees and better manage their expectations. The official line is that it takes, on average, 18 to 24 months for a case to be processed once it gets received by an RSC. However, as of March 2023, any nationality’s average processing time through USRAP was four years. One woman with a P-2 case said, “We have no idea how long things will take, and no one is telling us anything. You are the first people to even ask about our case, our lives. All we have are slips of paper that say ‘we will call you.’ When?!”

Processing the estimated 20,000 people with pending P-1 and P-2 cases currently in Pakistan is entirely doable. Almost 14,000 individuals completed their processing through the USRAP and arrived in the United States from countries throughout Africa in just the last eight months. And according to an employee of PRM, at least 3,000 Afghans have been processed for resettlement through Camp As Sayliyah (CAS) in Qatar since October 2022. Over the past year, the Biden administration has been rebuilding the USRAP infrastructure. And while the rate of resettlement is currently well behind reaching the ceiling of 125,000 people for (FY) 2023, PRM and USCIS are ramping up their operations and there are “several indicators that the USRAP pipeline is being restored.”

Absence of a Resettlement Support Center (RSC) in Pakistan

Despite Secretary Blinken’s commitment in 2021, there is currently no resettlement case processing of Afghans in Pakistan to the United States. PRM has indicated to Refugees International and other organizations following this issue that this is because there is not yet an RSC in Pakistan. PRM has proposed opening an RSC in Islamabad to be managed by IOM. An RSC would allow for pre-screening, preparation of case files, and hosting of DHS circuit rides. Representatives from across U.S. government agencies have told Refugees International that they are currently negotiating with the Pakistani government about establishing an RSC in Pakistan. Refuges International’s research trip to Pakistan confirmed that the government of Pakistan remains reticent to permit the United States to set up an RSC in the country. It is concerned about creating a “pull” factor, drawing more Afghans into Pakistan.

However, the potential pull factor is clearly not the only reason why the government of Pakistan is resisting an RSC. Some resettlement to other countries is taking place from Pakistan. In 2022, UNHCR Pakistan resumed its resettlement program that was non-operational since 2016 and submitted 3,504 Afghans for resettlement to six countries, including the United States. Most were PoR cardholders, but a handful were also new arrivals who underwent a UNHCR Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process. However, UNHCR has recently suspended submitting cases to the United States altogether at the request of PRM because without an RSC in Pakistan, the U.S. government is not processing any of their cases. Even without United States participation, by the end of 2023, UNHCR plans to submit 4,500 people to other countries accepting resettlement referrals from Pakistan, such as Australia, Canada, Germany, and Italy.

In addition to wanting to avoid a pull factor, the government of Pakistan appears concerned about the optics of a large U.S. presence that might come with an RSC. Diplomatic personnel from U.S. agencies often struggle to get approval for visas from the government of Pakistan. The prominent presence of an RSC in the capitol, populated with dozens of U.S. employees who would need approval to work in the country, would not necessarily be welcomed by many within the government of Pakistan and would also potentially draw attention to resettlement, thus exacerbating the perceived pull factor. To avoid the need for as many U.S. government employees to travel to Pakistan or wherever cases are processed, PRM should consider conducting at least a portion of the necessary interviews virtually. Some of the other resettlement countries accepting UNHCR referrals from Pakistan do this, and the United States can learn from them.

The U.S. government is continuing to negotiate with their Pakistani counterparts to establish an RSC, including at senior levels. However, after nearly two years with little progress, the United States should explore alternative lower-profile options for processing the P-1 and P-2 cases of recent Afghan arrivals.

One option would be to process at-risk Afghans currently living in Pakistan through CAS or another offsite location. PRM should test this option by identifying a group of high-profile Afghan women leaders with P-1 or P-2 cases in Islamabad and offer to fly them and their immediate family members to CAS to be processed for resettlement. At the same time as using CAS or if CAS is not viable, the United States could also utilize several of the twenty regional RSCs and sub-offices to process Afghan cases from Pakistan.

A second option that could start immediately, is to utilize the U.S. Embassy in Pakistan to process some cases and do so without drawing much attention to the program. The U.S. Embassy in Islamabad already has a significant presence, and it could dedicate some of its staff and space to conduct the necessary interviews and screening for resettlement processing. This option would likely not be a problem for the government of Pakistan because they allow limited resettlement to other countries through their embassies. A Pakistani official suggested this to Refugees International as a possible temporary solution to the impasse between the United States and Pakistan on this matter. A U.S. State Department official also confirmed that the United States can and has used embassies for processing.

A third option would be for PRM to set up a South and Central Asia regional RSC in a nearby country, such as Tajikistan or Nepal—where there has been an RSC in the past—willing to allow Afghan cases in the resettlement process to enter their territory. If PRM establishes a new RSC, it should ensure that the RSC and USCIS can implement concurrent, specialized processing. This would allow the RSC to complete all case processing in one location simultaneously rather than sequentially, similar to the CAS model or the models that have recently been applied in at least ten locations, including Guatemala, Türkiye, and Malaysia. Utilizing a new regional RSC would still require the government of Pakistan to issue exit permits. PRM would also need to provide some support for the refugees when they are at the RSC in the transit country.

Finally, if the Pakistani government and the U.S. government cannot agree upon a long-term RSC in Pakistan, they should explore setting up a temporary RSC in Pakistan to process just the approximately 20,000 people with P1 and P2 cases there now. The RSC’s operations would be time-bound for a three-to-five-year period to process Afghans in Pakistan who already have case numbers. This would limit resettlement eligibility to ease the Pakistani government’s concern about pull factors.

Conclusion

Afghanistan has experienced turmoil for decades, and Pakistan has generously hosted millions of Afghans who fled the instability in their own country over the years. In recent years, the Pakistani government has recognized more than 1 million Afghans as refugees, including them in public social services. But more than 2 million other Afghans remain without status, rights or services. The Pakistani government needs to be proactive in registering and recognizing these refugees as well as allowing UNHCR and NGOs to assist them. The situation is particularly alarming for those who have fled Afghanistan since August 2021. A small portion of these new arrivals have pending P-1 or P-2 cases for resettlement to the United States. The United States has little ability to protect at-risk Afghans who remain Afghanistan. However, it can assist these P-1 and P-2 cases of Afghans in Pakistan. In the face of resistance from the Pakistani government, the United States should consider every possible solution to process these cases. This is the very least these Afghan refugees are owed.

Endnotes

1 The use of the term “unregistered refugees” here refers to Afghans with Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC) and those with no documentation. Details about the ACC will be described later in the report.

2 For the purposes of this report, we will refer to all Afghans in Pakistan as refugees. The government of Pakistan only recognizes Afghans who arrived before 2005 and are also currently Proof of Registration (PoR) card holders as refugees. Therefore, the Afghans in Pakistan the team interviewed for this research technically have no status. But because they fled persecution in Afghanistan, we will refer to them as refugees.

3 These indicate the number of individuals, not the number of cases. The number of cases is lower because this number includes all eligible immediate family members.

Featured Image: Afghan refugee Najibi, 28, who was a pilot in the Afghan air force and who fled Afghanistan after the fall of Kabul in 2021, is photographed at a guesthouse run by the Future Brilliance charity on April 29, 2023 in Islamabad, Pakistan. Photo by Rebecca Conway © Getty Images