The Effect of COVID-19 on the Economic Inclusion of Venezuelans in Colombia

Preface

In most low- and middle-income countries, refugees and forced migrants face a range of legal, administrative, and practical barriers that prevent their economic inclusion. Removing these barriers would enable displaced people to become more self-reliant and more fully contribute to their host communities.

Such efforts are even more important as the world looks to economically recover from COVID-19. While the pandemic has created unprecedented challenges for low- and middle-income countries around the world, it has also highlighted the importance of expanding economic inclusion. Refugees and forced migrants can, and do, play a crucial role within labor markets. Given the opportunity, they can help their host countries recover from this crisis.

This case study / policy paper is part of the “Let Them Work” initiative, a three-year program of work led by the Center for Global Development (CGD) and Refugees International and funded by the IKEA Foundation and the Western Union Foundation. The initiative aims to expand labor market access for refugees and forced migrants by identifying their barriers to economic inclusion and providing recommendations to host governments, donors, and the private sector for how to overcome them. The primary focus is on refugees and forced migrants in Colombia, Peru, Kenya, and Ethiopia, with other work taking place at the global level.

To learn more about the initiative, please visit cgdev.org/page/labor-market-access and get in touch.

Helen Dempster

Project Manager for the “Let Them Work” initiative and Assistant Director, Migration, Displacement, and Humanitarian Policy

Center for Global Development

Introduction

Political unrest, economic and institutional collapse, violence, and human rights abuses in Venezuela are prompting millions of Venezuelans to flee their home country, causing one of the largest displacements in the history of Latin America. Colombia is by far the largest destination country for displaced Venezuelans, hosting almost 1.8 million as of May 2020. Since the beginning of the crisis in Venezuela, the Colombian government has maintained an open and constructive response towards the arrival of displaced Venezuelans. Prior to COVID-19, Colombia kept its borders open to Venezuelans, issued residence and work permits to over 700,000 individuals, and developed comprehensive inter-agency strategies for coordinating their response, which included providing humanitarian relief, and facilitating income generation for Venezuelans and host communities.

Despite this positive response, Venezuelans in Colombia have faced many obstacles to economic inclusion—defined as the achievement of labor income commensurate with one’s skills and decent work—both before and during the pandemic. Barriers to economic inclusion for Venezuelans in Colombia include a lack of legal access to the formal labor market, a lack of access to financial services, discrimination in hiring and in the workplace, a lack of information among employers about whether they can hire Venezuelans, and a high concentration of Venezuelans in areas with relatively few job opportunities. Consequently, Venezuelans in Colombia typically earn less than their Colombian peers and face high rates of poverty, widespread threats of eviction, and food insecurity.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has only compounded these challenges. As a result of the country’s economic lockdown and quarantine, Colombia’s GDP is predicted to fall by almost 8 percent this year, leading the country into its first recession in two decades. This economic slowdown is having severe effects on the Colombian labor market, with the unemployment rate reaching 19.8 percent in June 2020. As a result, Venezuelans have been pushed into an increased state of economic precarity, particularly because they are more likely than Colombians to work in sectors that have been highly impacted by the pandemic.

This policy paper is part of the Let Them Work initiative, co-led by the Center for Global Development (CGD) and Refugees International (RI). It summarizes many of the ideas from an accompanying case study that details the benefits of, and recommendations to achieve, greater economic inclusion for Venezuelans in Colombia. Furthermore, this piece explores the dynamics of greater economic inclusion in the context of COVID-19, discussing the impact of the pandemic on the Colombian economy and Venezuelans within the country. It describes the status of economic inclusion for Venezuelans in Colombia; highlights the benefits of greater economic inclusion in the context of COVID-19, and provides recommendations for government, donors, international organizations, and NGOs to simultaneously improve economic inclusion and COVID-19 response.

COVID-19 in Colombia

Starting in March and continuing through at least August, the Colombian government maintained one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. On March 16, the government closed its borders to migrants, including Venezuelans. It kept schools shut down, closed certain sectors of the economy, restricted public events and gatherings, instituted curfews, and limited internal travel. The Colombian government has gradually reopened the economy over the past few months, but many lockdown measures are still in place. For example, although the quarantine was partially lifted on September 1, some activities are restricted to specific days, bars remain closed, the number of flights is limited, and public gatherings are still banned.

In part due to the government’s proactive response, the initial spread of the virus in Colombia was relatively slow. However, although the daily case rate began decreasing in August (see figure 1), Colombia has the second highest rate of cumulative cases in Latin America and the fifth highest in the world. The situation has placed extreme pressure on the Colombian health system. In July, with hospitals facing overcrowding, the president of the Bogotá College of Medicine claimed that the city’s hospitals were “close to collapse,” and called for a complete lockdown of Bogotá. With high demand for COVID-19 care and limited resources, doctors in Bogotá began denying access to intensive care units (ICUs) for elderly patients with COVID-19 so that they could instead prioritize care for younger patients.

Figure 1. Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases per million people

The pandemic is also taking a serious economic toll. Given Colombia’s strong economic outlook preceding the pandemic, the country will experience one of the smallest contractions in Latin America—but the damage will nonetheless be immense. The IMF predicts that Colombia’s GDP will shrink by 7.8 percent in 2020. The effects of this downturn can be observed in the labor market. In June of 2020, the employment rate was 46.1 percent, down from 57.5 percent in June of 2019, and the unemployment rate was 19.8 percent, a 10.5 percentage point increase relative to the previous year.[1] These are by far the worst labor market outcomes the country has seen over the past decade, at least (figure 2).

Figure 2. Employment and unemployment rates in Colombia in June of each year

The government has pursued a series of measures in response to the economic impact of COVID-19. They have allocated US$3.7 billion (1.5 percent of GDP) for cash transfers to vulnerable families, tax deferrals for companies, subsidies to small businesses, and tax breaks for the poorest individuals. The government has also suspended mandatory pension contributions, opened new credit lines for the tourism and aviation sectors, and extended new labor protections, among other efforts. Furthermore, the country will receive an additional $700 million in loans from the World Bank to strengthen the response. The loan will support the government’s efforts to improve the health system, expand social programs, and expand guarantees, liquidity, and credit to enterprises. A number of other multilateral and bilateral aid agencies—most notably USAID—have also contributed to the response.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Venezuelans in Colombia

As mentioned above, Venezuelans in Colombia faced a wide range of barriers to economic inclusion even before the outbreak of COVID-19. As a result, even after controlling for other predictors of labor market outcomes (specifically age, sex, education, and location), Venezuelans were earning 30 percent less than Colombians on average as of October 2019. They were also far more likely to be working in the informal sector. Venezuelan women faced especially large wage gaps. As a result, many Venezuelans, and Venezuelan women in particular, were struggling to meet their basic needs.

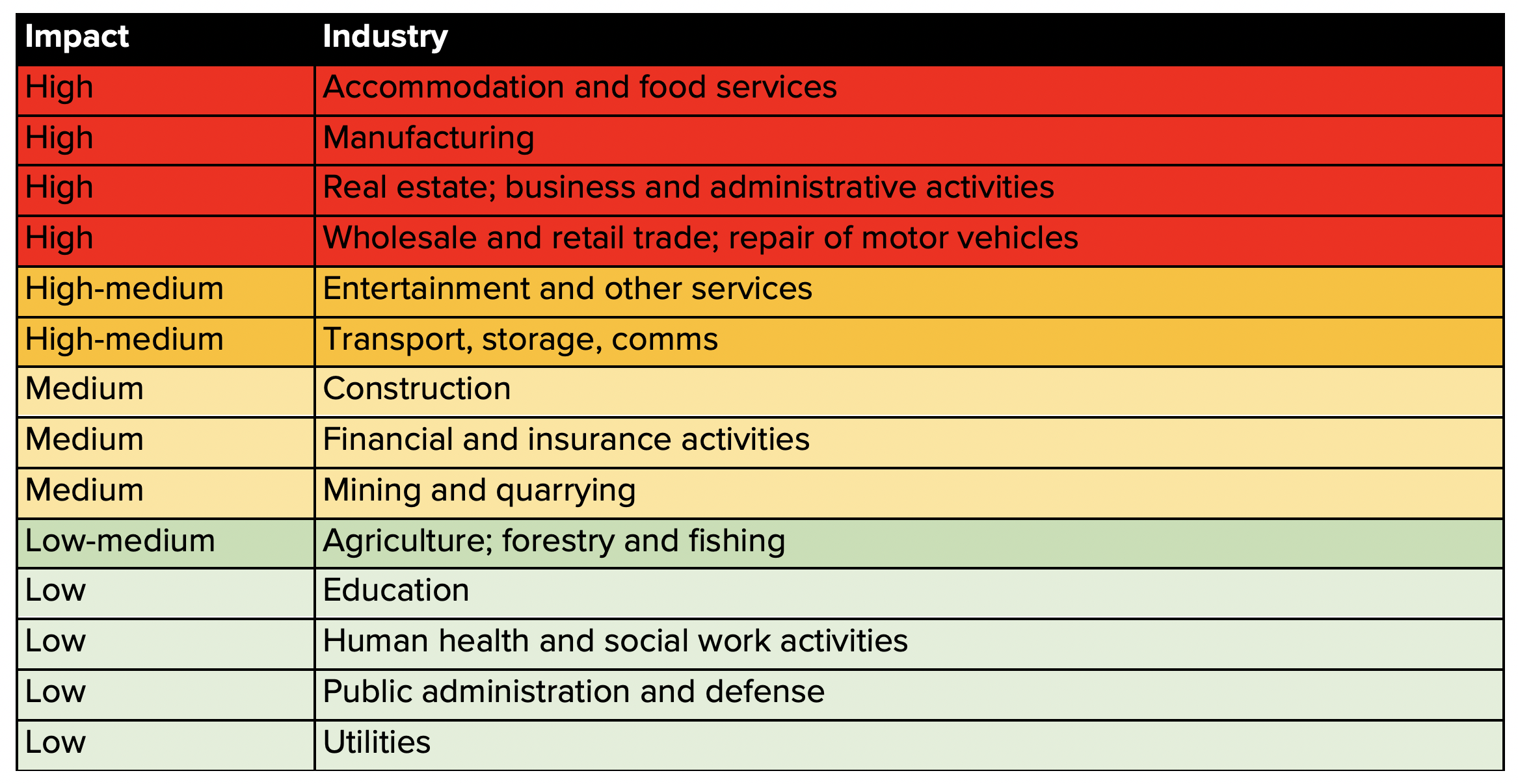

To understand the extent to which COVID-19 has exacerbated these difficulties, it is helpful to examine data on where Venezuelans work within the economy. According to the ILO, COVID-19 has negatively affected some sectors of the global economy—in terms of wages and employments rates—more than others (table 1).[2] Thus, if an employee or business owner was in a highly impacted sector before the outbreak, they are more likely to have lost their job or business or experienced losses of income.

Table 1. Global Impact of COVID-19 by Sector

The Colombian government’s nationally representative labor market data from August to October 2019 shows the proportion of Venezuelans working in each sector of the economy (figure 3). At the time of the survey, 64 percent of employed Venezuelans were working in highly impacted sectors, compared to 47 percent of employed Colombians. Only 3 percent of employed Venezuelans were in the least impacted sectors, compared to 13 percent of employed Colombians.[3] Furthermore, since many Venezuelans face tremendous obstacles to their economic inclusion, including legal and practical barriers that prevent them from accessing formal jobs, it may be more difficult for them to shift to sectors that have been less impacted.

Figure 3. Projected impact of COVID-19 on sector of employment

Venezuelan women have likely been even more adversely affected (figure 4), with 78 percent of employed Venezuelan women working in highly impacted sectors, compared with 57 percent of employed Venezuelan men and 59 percent of employed Colombian women.[4]

Figure 4. Proportion of employed Colombian and Venezuelan men and women working in highly impacted sectors

Venezuelans are also more likely to be working informally. And since informal workers have fewer workplace protections—which can prevent job and income loss—they may experience even more severe impacts from COVID-19. According to the survey, 46 percent of employed Venezuelans were working informally, compared to 35 percent of employed Colombians.[5]

The high rate of informal employment for Venezuelans is likely driven by the many barriers to economic inclusion that they face. These high rates of informality, in turn, drive their high rate of employment in highly impacted sectors—because the sectors dominated by informality also tend to be more highly impacted by the pandemic. Among all informal workers in Colombia at the end of 2019, over half work were working in highly impacted sectors. As such, efforts to lower labor market barriers for Venezuelans could help not only with their longer-term economic inclusion, but also with economic recovery during and after the pandemic.

Venezuelans’ labor market difficulties have translated into a wide range of challenges. According to surveys conducted before and after the imposition of the lockdown measures by the Interagency Group on Mixed Migration Flows (GIFMM, by its Spanish acronym), the percentage of Venezuelan families consuming three meals a day has fallen from 69 percent to 26 percent. Furthermore, eviction is widespread, 25 percent of Venezuelans say they do not know where they will live next month, and many families have been left homeless. Venezuelan women and girls are especially vulnerable. Rates of domestic violence are on the rise and, facing few other options, some may have to turn to negative coping mechanisms like survival sex. Even before the outbreak, some women and girls were forced to take these extreme measures; the economic crisis may force even more to do so.

Faced with these difficulties, thousands of displaced Venezuelans in Colombia are migrating on from Colombia, and many are even returning to Venezuela in desperation. A recent survey of Venezuelans in transit indicated that the loss of employment and evictions were the main drivers of migration from Colombia, playing a major role in forcing 77 percent and 40 percent, respectively, to relocate. While some are opting to migrate within Colombia or even to a new country, the majority are returning to Venezuela. Indeed, according to the Colombian migration authorities, from March 14 to August 3, over 95,000 Venezuelans returned to Venezuela. However, border closures by the Venezuelan government are making it difficult or impossible for many others to complete the journey. And even for those that do make it back to Venezuela, the economic situation in the country is as dire as ever, and the health system does not have the capacity to effectively handle the pandemic. Thus, many Venezuelans are forced to choose between two difficult options, with few economic opportunities or support systems in either Colombia or Venezuela.

Fortunately, the Colombian government and its partners have adapted their policies and programs to meet the needs of Venezuelans during the outbreak. In April, the government released a six-point plan for including Venezuelans in the pandemic response. As a part of the plan, the government is working with GIFMM partners to provide emergency cash transfers and access to food, shelter, and clean water. The government has also expanded insurance coverage for Venezuelans and guaranteed access to COVID-19 testing and treatment in public hospitals. At the same time, NGOs and humanitarian actors have adapted their programs to meet changing needs during COVID-19.

However, much more must be done to support Venezuelans and host communities alike. Venezuelans still face extreme economic vulnerabilities, and many Colombians are also suffering. Furthermore, there is a vast shortfall in funding for programs related to livelihoods, food security, health, education, protection, and more. As of October 5, only about 23.7 percent of the funding requirement for the regional Venezuela response under the Refugee and Migrant Response Plan (RMRP) had been met.

Venezuelan Economic Inclusion Amidst COVID-19: Progress, Gaps, and Benefits

In March, President Duque sought to implement measures to expand economic inclusion for Venezuelans in a way that would also improve the pandemic response. In an attempt to amplify the national health system’s capacity to cope with the pandemic, he announced that the government would work to accelerate the degree validation of Venezuelan health professionals. Similar policies had been enacted across the world, with countries like Peru and the United Kingdom implementing measures to include refugee medical professionals in the fight against COVID-19. With many Venezuelans in Colombia holding advanced medical degrees and experience in the health sector, this effort could have been an important step towards supporting the country’s strained health systems, while also allowing highly educated and experienced Venezuelans to fully utilize their skills in the economy. However, the medical community strongly opposed the effort, claiming that the country does not have a shortage of medical professionals. Despite this opposition, there have been reports of personnel shortages in intensive care units during the pandemic. Nonetheless, as a result of the pressure from the medical community, the government quickly retracted the policy.

The ongoing inability for medical professionals to verify their credentials is part of a broader set of barriers that limit economic inclusion for Venezuelans in Colombia. As mentioned above, these barriers include difficult processes for verifying credentials and skills, high levels of discrimination, a lack of legal access to the formal labor market, and a high concentration of Venezuelans in areas with high unemployment rates (such as Cucuta and Riohacha). The government identified these and other barriers in their income generation strategy for Venezuelans and host communities, which details both practical and legal obstacles to Venezuelan integration and establishes a roadmap of action for the Colombian government and its partners—including NGOs, donors, and other international organizations—to overcome them.[6] While the income generation strategy was created prior to the pandemic, the barriers that it identifies remain relevant.

However, the backlash from the medical community to expediting credential verification shows that there are major political obstacles to progress on the economic inclusion strategy, which are exacerbated by the rising levels of xenophobia. According to a survey by the Proyecto Migración Venezuela (Venezuela Migration Project), the percentage of respondents with an unfavorable view of Venezuelans in the country rose from 67 percent in February to 81 percent in April. As the pandemic continues to harm the Colombian economy, it is likely that xenophobia will continue to rise, as has been the case in other countries around the world.

Although local perceptions might tempt Colombian policymakers to further limit Venezuelan economic inclusion, doing so would be counterproductive. For instance, if Venezuelans were able to fully apply their skills in the labor market, they could increase firms’ productivity, leading to higher profits and more employment opportunities for locals. Greater economic inclusion would also translate into higher incomes and a higher rate of employment in the formal sector for Venezuelans. In fact, we estimate in the accompanying case study (using data from before the pandemic) that if all barriers to Venezuelans’ economic inclusion were lowered, Venezuelans’ average monthly income would increase from $131 to $186—which would translate into an increase of at least $996 million in Colombia’s annual GDP—and the total number of formal Venezuelan workers would increase from 293,060 to 454,107. And with higher incomes and more formal work, Venezuelans would experience lower rates of poverty, fewer protection concerns, less aid dependence, and faster recovery from the economic effects of COVID-19. They would also be able to spend more in the economy, leading to higher revenues for local businesses and increased fiscal revenues for the government.

These benefits are more relevant than ever as the needs and suffering among Venezuelans increases and the country remains trapped in an economic recession. With small businesses struggling, the potential boost in productivity offered by Venezuelans will be much needed. Facing large fiscal deficits, the government will need greater tax revenues. With a decrease in aggregate demand accompanying the recession, increased spending from Venezuelans could help stimulate the economy. And considering the high rates of unemployment, it will be important not to restrict Venezuelans only to the informal sector. This is because the presence of large refugee or migrant populations typically does not negatively impact wages or employment rates for locals—unless the refugees or migrants are confined to certain sectors of the labor market. Thus, by opening up the formal market to Venezuelans and lowering other barriers to formal work (such as the difficult credential recognition process), the Colombian government could reduce concentrated job competition and mitigate any negative labor market effects.

During the pandemic, the Colombian government and its partners have rightly been more focused on humanitarian support than economic inclusion. With limited economic opportunities for everyone and extreme vulnerabilities among Venezuelans, the most important measures have been those designed to help individuals meet their basic needs. The government has taken some actions during the pandemic that support Venezuelans’ economic integration, primarily through their attempt to include medical professionals in the COVID-19 response and through the delivery of cash-grants (in partnership with international organizations) to the most vulnerable—an effective tool for supporting livelihoods. However, considering the benefits that greater inclusion brings, it is important to shift even more towards a focus on economic recovery and inclusion.

Conclusion and Recommendations

COVID-19 is creating a widespread loss of livelihoods for Venezuelans and Colombians alike. However, the economic impacts of the pandemic are compounded for Venezuelans. Evidence in this paper shows that Venezuelans—and Venezuelan women in particular—are substantially more likely to be working in sectors highly impacted by COVID-19. The resulting loss in income is likely causing increased evictions, food insecurity, and poverty. As the economic and health crisis continues to affect Colombia, this is likely to continue. Greater economic inclusion for Venezuelans can help reduce these negative effects and support Colombia’s economic recovery. To facilitate economic inclusion in the aftermath of COVID-19, we recommend the following to the Colombian government and its partners.

The Colombian government should:

- Address political barriers to policy progress by maintaining a positive public stance towards Venezuelans, releasing statements that highlight the government’s support for economic inclusion, and scaling up anti-xenophobia efforts.

- Convene a dialogue with professional organizations to work towards an expedited credential verification process for medical professionals and others.

- Begin placing a greater focus on economic inclusion for Venezuelans—while maintaining humanitarian support.

- Create a plan of action to respond to the humanitarian needs of the Venezuelans that re-enter Colombia once the health crisis ends.

- Address the remaining policy barriers to Venezuelans’ economic inclusion, including a lack of channels for regularization and a lack of access to childcare and support services for women.

Donors, international organizations, and NGOs should:

- Increase funding under the RMRP to support activities related to the humanitarian response, Venezuelans’ economic inclusion, and Colombians’ economic recovery—which include livelihoods, food security, health, and protection programs, among others.

- Include Venezuelans in responses supported by other streams of funding, such as the World Bank’s loan to support Colombia’s COVID-19 response, ensuring that Venezuelans are taken into account in the recovery planning and programming.

- Facilitate economic inclusion through a range of programs and interventions, including by scaling up livelihood and anti-discrimination programs, rigorously evaluating these programs to maximize effectiveness, and facilitating voluntary relocation for Venezuelans to areas with more job opportunities.

- Adapt livelihoods programming to increase its effectiveness during the pandemic.[7]

[1] The employment rate measures the percentage of the working-age population that is employed. The unemployment rate measures the percentage of individuals participating in the labor force (i.e. working or looking for work) that are unemployed.

DANE, “Boletin Tecnico: Principales indicadores del mercado laboral, Junio 2020,” July 30, 2020 https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/ech/ech/bol_empleo_jun_20.pdf.

[2] Sectors are analyzed based on global real-time data from business data and surveys, including IHS Markit Global Business Outlook and Moody’s Analytics. For more on the methodology used to calculate impact by sector, see the Technical Appendix 3 of ILO, “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 3rd edition,” ILO Briefing Note, April 29, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_743146/lang–en/index.htm.

[3] Authors’ calculations based on: DANE, Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares, http://microdatos.dane.gov.co/index.php/catalog/599/get_microdata; LO, “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 3rd edition,” ILO Briefing Note, April 29, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_743146/lang–en/index.htm.

[4] Authors’ calculations based on: DANE, Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares, http://microdatos.dane.gov.co/index.php/catalog/599/get_microdata; ILO, “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 3rd edition,” ILO Briefing Note, April 29, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_743146/lang–en/index.htm.

[5] Authors’ calculations based on: DANE, Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares, http://microdatos.dane.gov.co/index.php/catalog/599/get_microdata; LO, “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 3rd edition,” ILO Briefing Note, April 29, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_743146/lang–en/index.htm.

[6] Gobierno de Colombia, “Estrategia de generación de ingresos para la población migrante proveniente de Venezuela y las comunidades de acogida,” November 2019.

[7] See the recent CGD-RI-IRC report for details on how implementing organizations can adapt economic inclusion programming during the pandemic:

Helen Dempster, Thomas Ginn, Jimmy Graham, Martha Guerrero Ble, Daphne Jayasinghe, and Barri Shorey, “Locked Down and Left Behind: The Impact of COVID-19 on Refugees’ Economic Inclusion,” Center for Global Development, Refugees International, and the International Rescue Committee, July 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/locked-down-left-behind-refugees-economic-inclusion-covid.pdf.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Helen Dempster, Thomas Ginn, Cindy Huang, Hardin Lang, Sarah Miller, Daphne Panayotatos, Rachel Schmidtke, and Eric Schwartz for their invaluable feedback and comments on this paper.

Cover Photo: © UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso