The Effect of COVID-19 on the Economic Inclusion of Venezuelans in Peru

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Sarah Miller, Thomas Ginn, Cindy Huang, Hardin Lang, Marina Navarro, Rachel Schmidtke, and Eric Schwartz for their invaluable feedback and comments on this paper.

Preface

In most low- and middle-income countries, refugees and forced migrants face a range of legal, administrative, and practical barriers that prevent their economic inclusion. Removing these barriers would enable displaced people to become more self-reliant and more fully contribute to their host communities.

Such efforts are even more important as the world looks to recover economically from COVID-19. While the pandemic has created unprecedented challenges for low- and middle-income countries around the world, it has also highlighted the importance of expanding economic inclusion. Refugees and forced migrants can, and do, play a crucial role within labor markets. Given the opportunity, they can help their host countries recover from this crisis.

This policy paper is part of the “Let Them Work” initiative, a three-year program of work led by the Center for Global Development (CGD) and Refugees International, and funded by the IKEA Foundation and the Western Union Foundation. The initiative aims to expand labor market access for refugees and forced migrants, by identifying their barriers to economic inclusion and providing recommendations to host governments, donors, and the private sector for how to overcome them. The primary focus is on refugees and forced migrants in Colombia, Peru, Kenya, and Ethiopia, with other work taking place at the global level.

To learn more about the initiative, please visit cgdev.org/page/labor-market-access and get in touch.

Helen Dempster

Project Manager for the “Let Them Work” initiative

Assistant Director, Migration, Displacement, and Humanitarian Policy

Center for Global Development

Introduction

Peru is the second largest destination country for displaced Venezuelans abroad, hosting about 1,043,460 Venezuelans. As displaced Venezuelans first began arriving in Peru, the Peruvian government was welcoming. It allowed any Venezuelan with a national ID card to enter the country and provided a temporary stay permit (PTP, by its Spanish acronym)—which grants the legal right to work and access basic services—to all Venezuelans that entered the country regularly. Today, over 477,000 Venezuelans in Peru have either been granted a PTP or another form of legal residence in the country.

However, in October 2018, the government stopped issuing new PTPs. And in June 2019, they introduced a visa requirement for any Venezuelan attempting to enter Peru. The new requirement, which is still in place today, is almost impossible for most to fulfill, and thus pushes many Venezuelans to apply for asylum instead. But even asylum-seekers face challenges. Those entering through official land entry ports are forced to wait at the border during the initial stages of processing their asylum claims. And even once they are allowed into the country where they can continue their asylum process, most still cannot access the formal labor market in practice, and few achieve refugee status. In fact, by 2019, nearly 500,000 Venezuelans had applied for asylum in Peru, but only 1,230 had been granted refugee status. As a result of the limited viable options for formal entry and regular status, the number of Venezuelans with irregular status in Peru is on the rise. (Sources: here, here, and here).

In response to this situation, at the end of October 2020, the government issued a decree aimed at regularizing Venezuelans already inside Peru and providing them with work permits. Once it is implemented in the upcoming months, the Temporary Stay Permit License (Carnet de Permiso Temporal de Permanencia or CPP) will serve as an extension of the PTP, but only for Venezuelans already inside the country. While the measure is a step in the right direction, the permit has several key drawbacks, which will prevent many Venezuelans from obtaining it. For instance, it requires applicants to present valid passports and to pay a fee based on the amount of time spent in the country irregularly.

As a result of these and other challenges, Venezuelans in Peru—regardless of their migratory status—face tremendous practical and legal obstacles to economic inclusion, which we define as the achievement of labor income commensurate with one’s skills and decent work. Consequently, most Venezuelans work in informal, low-paying jobs that do not match their qualifications, where they often suffer from exploitation and abuse.

This difficult economic situation for Venezuelans has been exacerbated by COVID-19. With Peru’s GDP predicted to fall by nearly 14 percent this year, the country as a whole is suffering. Furthermore, Venezuelans, who are more likely to work in highly impacted sectors than Peruvians, have been disproportionately affected by the economic downturn. They were also earning far less on average before the pandemic. And, many have been pushed into a state of extreme economic precarity, facing food insecurity, eviction, and homelessness.

This policy paper explores these dynamics in detail, discussing the impact of COVID-19 on the Peruvian economy and on Venezuelans within the country. It also highlights recent progress on Venezuelan economic inclusion in Peru, discusses the benefits of increased economic inclusion, and provides recommendations to simultaneously improve economic inclusion and the COVID-19 response.

COVID-19 in Peru

The Peruvian government instituted severe measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. On March 15, the government declared a state of national health emergency and implemented a country-wide quarantine. The measure included the closure of all borders to non-commercial transportation, and restrictions on freedom of movement and freedom of assembly. Furthermore, a curfew from 5 P.M. to 8 A.M. was instated, and only essential businesses—such as pharmacies, banks, and grocery stores—were allowed to operate.

Although some lockdown measures and curfews in some areas of the country remain in effect, the Peruvian government has begun reopening the economy in recent months. In May, the government announced plans to gradually resume economic activities. Mining, industry, construction, and trade services were among the first to be resumed. In July, they announced plans to reactivate 95 percent of the economy. Sources: here, here, and here.

Despite the implementation of timely and strict measures, by August 2020, Peru had the highest COVID-19 fatality rate in the world. Indeed, Peru currently has the sixth largest number of cases of COVID-19 infections per capita in the world, and the second largest in the region (behind Colombia). The John Hopkins University Center for Systems and Science Engineer (CSSE) reports that by October 1, 2020, Peru had a total of 814,829 cases of COVID-19 and 32,463 deaths. The high caseload may be partly due to a combination of the following factors:

- some lockdown measures, such as restrictions on economic activities, were not well enforced;

- the country has a large informal sector and it is difficult for many informal workers to stop working or work from home;

- many food markets remained open and crowded; and

- the distribution of government grants to assist families was conducted in a way that created close contact among recipients. Sources: here and here.

However, it is certainly possible that other factors were major contributors to the large outbreak. Furthermore, many of the identified factors are also present in other countries with smaller outbreaks, so it is hard to pinpoint why exactly the infection rate is so high in Peru.

The pandemic has had a tremendous economic impact on Peru. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has predicted that Peru’s GDP growth will fall by 13.9 percent in 2020. This contraction is devastating the country’s labor market. In the second quarter of 2020, the rate of employment in Lima was about 28 percent, 55 percent lower than it was for the same period in 2019 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of people employed in Lima in the second quarter of each year

In response to the economic impact of COVID-19 on the livelihoods of Peruvians, the government announced a stimulus package amounting to about 12 percent of GDP. The package included cash transfers targeting poor families and independent workers, financial support to small businesses, exemptions from pension contributions, an extension on the deadline to pay taxes, VAT exemptions for certain businesses, and other efforts.

The impact of COVID-19 on Venezuelans in Peru

Even before COVID-19, Venezuelans faced numerous barriers to economic inclusion in Peru. For example, hundreds of thousands still do not have the legal right to work. They also face xenophobic discrimination, difficult processes for verifying their credentials and skills, limits on the number of foreign workers Peruvian businesses can hire, and other practical and legal barriers.

Unsurprisingly, Venezuelans in Peru have worse economic outcomes than Peruvians, on average. As of December 2018, about 72.5 percent of Peruvians worked in the informal sector, compared to about 88.5 percent of Venezuelans. Relatedly, many Venezuelans are working in jobs where their skills are not adequately utilized. Venezuelans also earn about 35 percent less than Peruvians on average. The income gap is starkest among Venezuelans with a university education, who earn 71 percent less than their Peruvian counterparts. Furthermore, Venezuelans suffer from exploitation and abuse at a higher rate than Peruvians, often working longer hours for less money, and facing harassment from both employers and authorities.

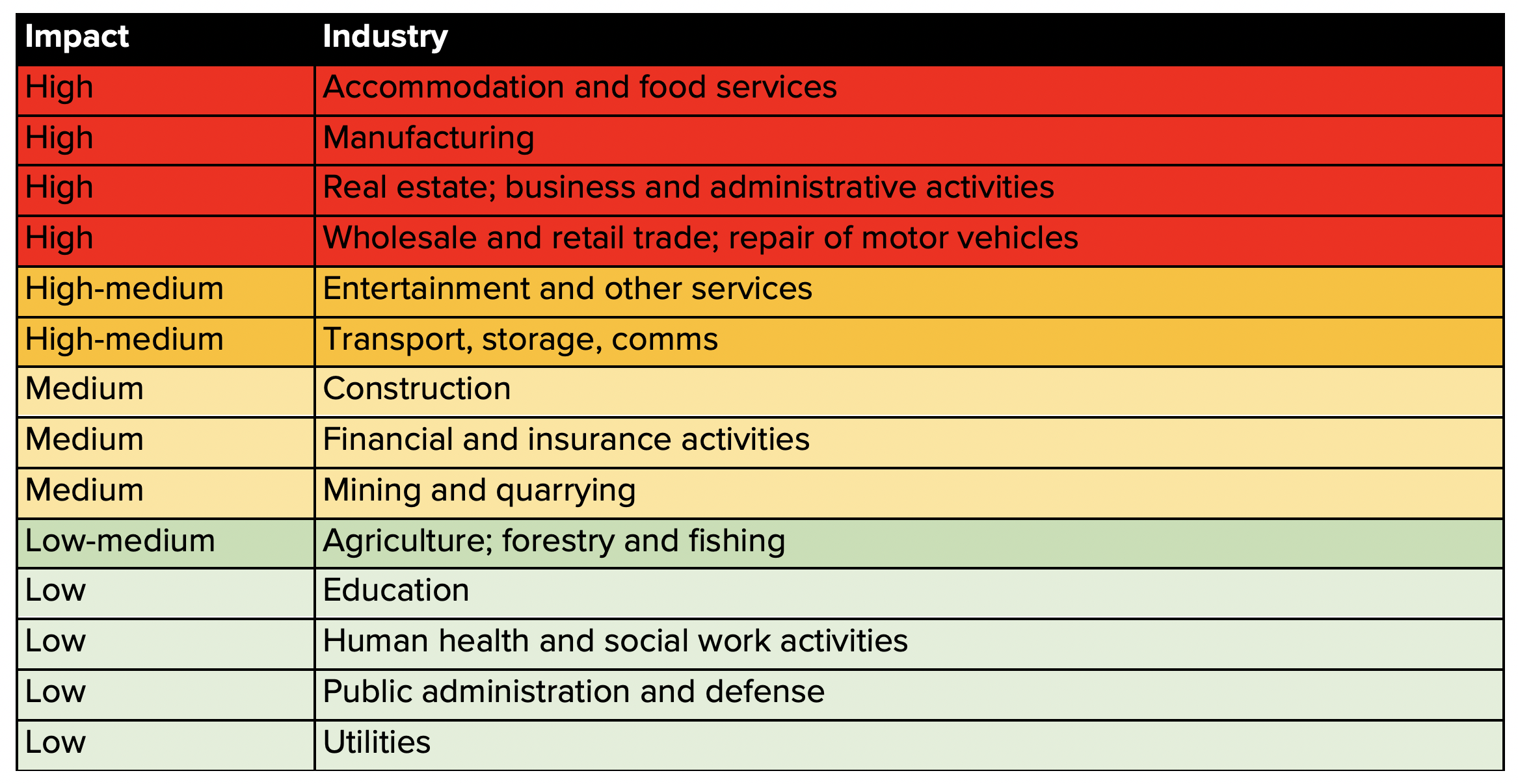

To understand the extent to which COVID-19 has exacerbated these difficulties, it is helpful to examine data on the sectors in which Venezuelans work. According to the ILO, COVID-19 has negatively affected some sectors of the global economy more than others (see table 1). The more impacted the sector is, the more likely employees or business owners in the sector are to lose their job or business or experience losses of income.

Table 1: Global Impact of COVID-19 by Sector

The Peruvian government’s labor market data from December 2018 shows the proportion of Venezuelans working in each sector of the economy (figure 2).[1] Over half of all workers, including Peruvians, appear to be in highly impacted sectors. However, Venezuelans appear to be harder hit. At the time of the survey, 71 percent of employed Venezuelans were working in highly impacted sectors, compared to 56 percent of employed Peruvians. Only 4 percent of employed Venezuelans were in low impact sectors, compared to 14 percent of employed Peruvians.

Figure 2. Projected impact of COVID-19 on sector of employment

Venezuelan women are likely to have been even more adversely affected (figure 3). Approximately 78 percent of employed Venezuelan women were working in highly impacted sectors, compared with 67 percent of employed Venezuelan men, and 67 percent of employed Peruvian women. It is important to emphasize that, because the labor market data are from the end of 2018 and the categorization of sectors by level of impact are based on global data, these are only rough estimates. Nonetheless, they provide a general picture of the likely differences in impacts across Peruvians and Venezuelans.

Figure 3. Proportion of employed Peruvian and Venezuelan men and women working in highly impacted sectors

Pre-existing economic difficulties, coupled with the disproportionate impact of COVID-19, have pushed Venezuelans into an increased state of precarity. An April 2020 survey of Venezuelans in Peruvian urban areas by the Centro para el Desarrollo Económico (the Center for Economic Development, CenDE) found that only 5 percent of respondents reported having enough money to meet their basic needs. In May, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that around 200,000 Venezuelans in Peru were in urgent need of food assistance. Furthermore, the April survey by CenDE found that 51 percent of Venezuelans were at risk of eviction. Due to the health emergency, 40 percent of the shelters in Peru have reduced their occupancy, and 44 percent have closed their doors to newcomers. Moreover, the isolation measures have affected the delivery of programs to support Venezuelans, including water, sanitation, and health services. As a result, many Venezuelans have been forced to sleep in the streets and some are even opting to make the unthinkable trip back home to Venezuela, where the economic and political crisis persists. Source: here and here.

The situation of some Venezuelans in Peru is further exacerbated by their need to send remittances home to support their families in Venezuela. In 2018, 66.5 percent of the Venezuelan population in Peru reported sending remittances home. As a displaced Venezuelan mentioned in an interview with Refugees International:

“My sister moved to Peru because the money that I was able to send to Venezuela wasn’t enough. […] Once the quarantine started, my sister lost her job. […] Now, I am the one in charge of sustaining my family, but I don’t make enough to pay for rent, food, transportation, and send money back home.”[2]

The decreased ability of Venezuelans in Peru to send remittances will have a double impact, affecting Venezuelans in Peru and their families back at home. As Venezuela also suffers from the consequences of the pandemic, remittances may become increasingly important for families to survive. Therefore, the impact of COVID-19 on Venezuelans in Peru is likely to increase the suffering for Venezuelans beyond the Peruvian border.

The Government of Peru has rightly provided social support to Peruvians during the pandemic but has left Venezuelans out of their planning and response. For example, Venezuelans in Peru are not able to benefit from any of the government cash grants to support families during the pandemic. And, although the Peruvian government has temporarily extended access to public health services for Venezuelans with regular status who have COVID-19 symptoms, those with irregular status are left out of the health response. Moreover, NGOs on the ground mentioned that, in practice, even Venezuelans with regular status have issues accessing health services due to fear of harassment by authorities and a lack of awareness among hospital staff as to whether they can admit patients with PTPs or other types of documentation.[3]

Fortunately, NGOs and donors have increased funding to assist Venezuelans. For instance, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded a program implemented by World Vision to provide emergency cash transfers to Venezuelan families in Peru. Similarly, the platform for the response to Venezuelan displacement to Peru—the Working Group on Refugees and Migrants (GTRM, by its Spanish acronym)—has led the delivery of food, shelter, and cash assistance to Venezuelan families in Peru. By the end of May 2020, the GTRM had distributed over US$1.6 million in Cash-Based Interventions (CBI), benefitting over 31,000 Venezuelans.

However, many Venezuelans are still in need of major humanitarian assistance, facing food insecurity, risk of eviction, and a lack of medical care. There also remains a significant funding deficit. By August 31, 2020, only 29.5 percent of the total $148.6 million required for the GTRM’s response had been covered. These funds are reaching only about 150,000 people in need, including Venezuelans and host communities, leaving many others without access to adequate support. It is therefore crucial to increase support, continue adapting programs to reach Venezuelans during COVID-19, and make policy progress that allows for greater economic inclusion.

Venezuelan economic inclusion amidst COVID-19: progress, gaps, and benefits

During the pandemic, there has been some progress on Venezuelan economic inclusion in Peru. Besides the implementation of a new regularization measure for Venezuelans inside Peru, in April 2020, the Peruvian government took important steps to integrate Venezuelans into the COVID-response. For instance, in April 2020, recognizing the potential to leverage Venezuelans’ skills to combat the virus, the government created the special COVID-19 task force, “Servicer,” which temporarily integrated foreign health professionals into the COVID-19 response unit (Source here and here). The creation of Servicer was a good first step towards greater inclusion of Venezuelans. However, it was only a temporary measure, and limited their inclusion to COVID-19-related services. In August 2020, the government of Peru issued another decree that allows Venezuelan medical professionals to work in the central Peruvian health system, beyond Servicer. The new decree (N. 090-2020) allows Venezuelan health professionals to validate their diplomas and exercise their profession with only an apostille—a certificate that verifies the validity of their foreign degree—both during and after the health crisis. Considering the fact that the process of verifying credentials has been a major impediment to labor market access for Venezuelans in Peru, these measures represent a major step forward toward greater economic inclusion.

Even prior to the pandemic, the government of Peru committed to improve the integration of Venezuelans in the country. For instance, at the Global Refugee Forum (GRF) in December 2019, the Peruvian government pledged to acknowledge the qualifications of Venezuelan doctors, teachers, and engineers. With the measures implemented to integrate Venezuelan health professionals in the health system, the Peruvian government made a big first step towards realizing this pledge.

However, the Peruvian government still has a long way to go. They have yet to fulfill their other GRF commitments, including acknowledging qualifications of Venezuelan teachers and engineers, providing residence permits to asylum seekers, and enrolling refugee children in schools. Moreover, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans lack the legal right to work, most Venezuelans face a wide range of other legal and practical barriers to economic inclusion, and many lack access to healthcare.

Unfortunately, there is a risk that rising xenophobia in the country will deter the government from making progress on these issues. Since 2018, perceptions towards Venezuelans in Peru have been worsening. For instance, a 2019 study indicated that 81 percent of Peruvians agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “many Venezuelans in Peru were criminals,” compared to 55 percent in the previous year. Furthermore, since attitudes towards migrants tend to worsen during a recession, xenophobic attitudes will likely continue to grow. Besides, the upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections of April 2021 increase the risk of Venezuelans becoming scapegoats for politicians aspiring to office.

Widespread negative attitudes certainly make it difficult for the government to maintain an inclusive stance towards Venezuelans, especially when it is facing many other demands in meeting the COVID-19 crisis. However, it is crucial to continue pushing for progress. Including Venezuelans in the economy and COVID-19 response would lead to substantial improvements in the health and economic situation of Peruvians and Venezuelans alike. Denying their inclusion would exacerbate existing challenges.

When refugees and forced migrants are included in the economy, they can increase firms’ productivity by filling jobs that are of less interest to locals and by contributing unique skills. As a result, the businesses for which they work may earn higher profits, which lead to new employment opportunities. Greater economic inclusion for Venezuelans would also allow them to earn higher incomes, and thus increase their self-reliance. Higher incomes would, in turn, allow them to spend more in the economy, creating increased fiscal revenues and revenues for local businesses. These benefits have already been observed in Peru. Even with the existing barriers to their economic inclusion, Venezuelans in Peru have already had a positive net fiscal impact (i.e., they have contributed more to tax revenues than government spending) and positive impacts on the country’s economic growth (Sources here and here). And according to the Central Bank of Peru, in 2018, 0.3 percentage points of annual GDP growth could be attributed to the migrant population in Lima and Callao. Venezuelans’ comparatively high levels of education could also help Peru to achieve its development goals, such as improving the country’s economic competitiveness and diversifying the economy.

Greater economic inclusion for Venezuelans could also improve labor market outcomes (i.e. wages and employment rates) for Peruvians. Typically, the arrival of large refugee or migrant populations does not create adverse labor market effects. But there is evidence that these negative effects are more likely when refugees are confined to specific sectors of the labor market (Sources here and here). Unfortunately, the large barriers to economic inclusion are currently confining many Venezuelans to the informal labor market. Therefore, by opening up the formal market to Venezuelans that are already in the country, the Peruvian government could reduce concentrated job competition and, as a result, mitigate potential adverse labor market effects. Given the economic recession and high unemployment rates facing Peru, these benefits are more important than ever.

It is important to acknowledge that even with all the positive labor market benefits of greater economic inclusion, some Peruvians may still experience some setbacks. For example, if economic inclusion leads to more Venezuelans entering the formal sector, there may be some degree of job displacement among formal workers. So, even if there is a positive averageeffect on formal sector wages and employment rates as a result of Venezuelans enhancing business productivity, some formal workers may lose while others gain. In other words, although the net gains of greater economic inclusion for Peruvians across the formal and informal sectors should be positive, some Peruvians may be negatively affected. It is therefore crucial for international actors to work with the government to support those who may be negatively impacted, especially through livelihood programs.

It is also important to include Venezuelans in the country’s overall COVID-19 response and recovery strategy. Excluding Venezuelans from stimulus measures and social safety nets only serves to hurt the broader economy and undermine efforts to combat the pandemic. For instance, denying cash assistance to Venezuelans forces many to work outside the home—despite the quarantine measures—which exposes them to the virus and may lead to higher rates of contagion throughout the country. However, it is important to acknowledge that the government must make difficult choices about allocating limited funds. There are also political pressures to focus spending on Peruvian citizens. To address this problem, the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) should provide grants to cover the cost of including Venezuelans in the COVID-19 response. These grants should of course be conditional on Venezuelans’ full inclusion in the response.

COVID-19 does not discriminate based on nationality or immigration status, and neither should governments in their policy responses. Despite the financial and political difficulties of responding to the challenges ahead, it is critical to implement inclusive policies that contain the economic and health effects of the pandemic. Including Venezuelans in the planning and response of COVID-19 would not only support a more inclusive economic recovery, but would also limit the spread of the disease. As Peru faces unprecedented social and economic challenges, Venezuelans can serve as allies to build a stronger and more resilient economy that does not leave anyone behind.

Recommendations and Conclusions

COVID-19 is creating a widespread loss of livelihoods for Venezuelans and Peruvians alike. However, the economic impacts of the pandemic are compounded for the hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans in Peru. Evidence in this policy paper shows that Venezuelans—and Venezuelan women in particular—are substantially more likely to be working in sectors highly impacted by COVID-19. This is causing an increased risk of evictions, food insecurity, and poverty. As the economic and health crisis continues to affect Peru, the negative consequences for Venezuelans are likely to continue. Greater economic inclusion for Venezuelans can help reduce these adverse effects and support Peru’s economic recovery. To facilitate economic integration, we recommend the following to the Peruvian government and its partners.

The Peruvian government should:

- Include Venezuelans in the national COVID-19 Response and Recovery Strategy, allowing vulnerable Venezuelans to benefit from future COVID-19 stimulus efforts, including household grants and business subsidies.

- Follow through on the commitments made at the Global Refugee Forum, such as facilitating the credential recognition process for Venezuelan teachers and engineers, providing residence permits to asylum seekers, and enrolling all refugee children in schools.

- Publicly express support for Venezuelans’ economic inclusion as a means to combat rising xenophobia.

- Expand access to COVID-19 health services to all Venezuelans regardless of their migratory status.

- Address the remaining policy barriers to Venezuelans’ economic inclusion, including the remaining barriers to regularization associated with the new work permits, difficult processes for verifying credentials and degrees, the lack of information among businesses on the legality of hiring Venezuelans, quotas on hiring foreigners, higher tax rates for foreigners working in the formal sector, and a lack of access to public childcare and support services for women. (Source here)

Donors, international organizations, and NGOs should:

- Extend grants—especially though the World Bank and IDB—to cover the costs of including Venezuelans in the COVID-19 response and related stimulus packages. The grants should be conditional on the inclusion of Venezuelans in these measures.

- Increase funding to support the humanitarian response, Venezuelans’ economic inclusion, and Peruvians’ economic recovery.

- Facilitate economic inclusion through a range of programs and interventions, including by scaling up livelihood and anti-discrimination programs, rigorously evaluating these programs to maximize effectiveness, and working with the government to facilitate credential recognition.

- Adapt economic inclusion programming to increase its effectiveness during the pandemic, including by shifting to digital delivery platforms.

Endnotes

[1] The data on Peruvians are from the Encuesta Permanente Nacional (EPE) for October-December of 2018. The data on Venezuelans are from ENPOVE, for December of 2018. EPE is representative of Lima and Venezuelans are not necessarily excluded. ENPOVE is representative of five cities in Peru, where 85 percent of the Venezuelan population resided at the time of the survey: Lima y Callao, Tumbes, Trujillo, Cusco, y Arequipa. All individuals age 15 and above that report an industry of occupation within one of the ILO impact categories are included in estimates. Encuesta permanente nacional (EPE) http://iinei.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/; Encuesta dirigida a la población venezolana que reside en el país (ENPOVE) http://iinei.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/.

[2] Remote interview conducted with a displaced Venezuelan in Peru, April 2020.

[3] Based on an interview with NGOs in Peru in June and August 2020.

Cover Photo: UNHCR/Sebastian Castañeda